Approved April 2014

NCTE has long-established positions on class size for English language arts teachers. In 1960 it adopted a policy that secondary teachers of English should teach a maximum of 100 students per day, and that elementary teachers should have a comparable load. In 1971 it passed a resolution to inform local, state, and national administrators and policymakers about this policy. In 1983 and again in 1995 there were resolutions urging more attention to the issue of class size. And in 1999 NCTE issued a position statement on class size and teacher workload.

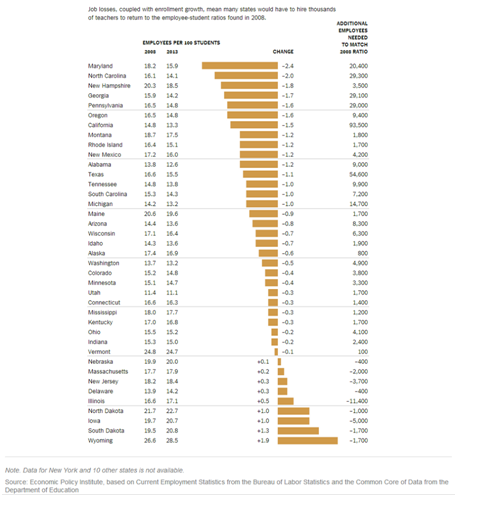

Today public schools employ 250,000 fewer people than before the recession of 2008–09, while enrollment has increased by 800,000, and class sizes in many schools are at record highs (Rich, 2013). Recent research tells us why this matters:

What Is Class Size?

What Is Class Size?

In research on early elementary school students, small classes usually mean fewer than 20 students, while for high school students the definition of “small” classes is usually somewhat larger. There are similar variations in what constitutes small classes for college writing instruction. In addition to the ambiguity about how many students constitute a smaller class, researchers use different strategies for assigning a class-size number. It can mean the number of students enrolled in the course, the number of students completing the course, or the number of students completing major course assignments (Arias & Walker, 2004). Furthermore, there is a shifting relationship between class size and teacher workload. Reducing class size can, for example, increase teacher workload if the number of students per class is lowered but teachers are assigned one more class per day.

Academic Performance

Overall, research shows that students in smaller classes perform better in all subjects and on all assessments when compared to their peers in larger classes. In smaller classes students tend to be as much as one to two months ahead in content knowledge, and they score higher on standardized assessments. It is worth noting, however, that some studies analyze student assessment results in terms of individual student performance and others in terms of class-wide aggregated performance, which can obscure the differences in individual students’ performances.

These positive effects of small class sizes are strongest for elementary school students, and they become more powerful and enduring the longer students are in smaller classes. That is, students who have smaller classes in early elementary grades continue to benefit from this experience even if they are in larger classes in upper elementary or middle school (Bruhwiler & Blatchford, 2011; Chingos, 2013).

Despite the generally positive effects of smaller classes, the benefits are not consistent across all levels and populations. Small classes make the biggest difference for early elementary school students, while for many high school students smaller classes do not make a significant difference in academic performance. However, for minority and at-risk students as well as those who struggle with English literacy, smaller classes enhance academic performance. Class size also shapes the quality of writing instruction at all levels, including college, because smaller classes are essential for students to get sufficient feedback on multiple drafts. Not surprisingly, smaller writing classes increase retention at the college level (Blatchford et al., 2002; Horning, 2007).

Student Engagement

Academic performance is important, but it is not the only measure of student success. In the area of student engagement, findings consistently show the value of small classes. Students talk and participate more in smaller classes. They are much more likely to interact with the teacher rather than listen passively during class. Not surprisingly, students describe themselves as having better relationships with their teachers in smaller classes and evaluate both these classes and their teachers more positively than do their peers in larger classes. Students display less disruptive behavior in small classes, and teachers spend less time on discipline, leaving more time for instruction. Specifically, teachers in smaller classes can diagnose and track student learning and differentiate instruction in response to student needs. In smaller classes students spend less time off-task or disengaged from the work of the class, and they have greater access to technology. Research also suggests that smaller class sizes can help students develop greater ability to adapt to intellectual and educational challenges (Bedard & Kuhn, 2006; Dee & West, 2011; Fleming, Toutant, & Raptis, 2002).

Long-Term Success

The benefits of smaller classes extend beyond test scores and student engagement. In addition to the longer-term positive attributes of small class sizes in the early grades, benefits include continued academic and life success. Researchers have found that reducing class size can influence socioeconomic factors including earning potential, improved citizenship, and decreased crime and welfare dependence. The beneficial effects of being assigned to a small class also include an increased probability of attending college. This benefit is greatest for underrepresented and disadvantaged populations. While the increased probability for all students is 2.7%, it is 5.4% for African American students and 7.3% for students in the poorest third of US schools (Dynarsky, Hyman, & Schanzenbach, 2013; Krueger, 2003).

Teacher Retention

Teacher quality has, for some time, been recognized as the most important variable in the academic success of students. Recruiting and retaining effective teachers has become increasingly important as school districts impose mandates about student test scores and overall academic performance. Class size has an effect on the ability to retain effective teachers because those with large classes are more likely to seek other positions. Research indicates, however, that instead of rewarding effective teachers by decreasing their class size, administrators often increase the class sizes of the most effective teachers in order to ensure better student test scores (Barrett & Toma, 2013; Darling-Hammond, 2000; Guarino, Santibañez, & Daley, 2006).

The Cost Factor

One of the most common arguments against smaller class sizes is financial. School districts claim that they cannot afford to reduce the size of classes because it would be too expensive. However, it is also expensive when students leave public schools to attend private ones. Research shows that class size is a significant factor in parents’ decisions to send their children to private schools. Despite the enormous emphasis on test scores in public schools, parents report little interest in these scores when choosing a school. Instead, two of the top five reasons parents give for choosing a private school are “smaller class sizes” (48.9 %) and “more individual attention for my child” (39.3%). The other three reasons are better student discipline, better learning environment, and improved student safety, all of which are influenced by class size (Kelly & Scafidi, 2013).

Recommendations

Class size is a major factor in student learning. To be sure, it is one of several important factors, and more research is needed to determine how it interacts with phenomena such as teacher quality and context, but existing research should guide policy decisions in several ways.

- Do not conflate class size and teacher workload.

Class size can refer to enrollment in or completion of a given class or program of study, and each of these has different implications for a teacher’s workload. If a large number of students enroll but do not complete a course, for example, the ratio of class size to workload will shift depending upon whether enrollment or completion is considered. Furthermore, requiring teachers to teach more classes with smaller numbers of students in each does not constitute a decrease in workload.

- Recognize that the benefits of reduced class size are not uniform across all grades and populations.

Although more research is needed to understand the full effect of class size, existing research shows that younger students, at-risk students, and special-needs students receive greater benefit from small classes than other populations.

- Consider the differential effects of class size across the disciplines.

Most research on class size does not distinguish among disciplines, so it is easy to assume that an increase or decrease in class size will have the same effect in every classroom. However, a class that assesses student learning with multiple choice tests may not receive as much benefit from a reduction in class size as a class that assesses student learning with written essays.

- Use multiple measures to evaluate the effects of reducing class size.

Since class size interacts with several dimensions of learning that extend beyond what can be measured with a standardized test, it is important to use several different measures to determine the effects of making classes smaller.

References

Arias, J. J., & Walker, D. M. (2004). Additional evidence on the relationship between class size and student performance. Journal of Economic Education 35(4), 311–329.

Barrett, N., & Toma, E. F. (2013). Reward or punishment? Class size and teacher quality. Economics of Education Review 35, 41–52.

Bedard, K., & Kuhn, P. J. (2006). Where class size really matters: Class size and student ratings of instructor effectiveness. Economics of Education Review 27, 253–265.

Blatchford, P., Goldstein, H., Martin, D., & Browne, W. (2002). A study of class size effects in English school reception year classes. British Educational Research Journal, 28(2), 169–185.

Bruhwiler, C., & Blatchford, P. (2011). Effects of class size and adaptive teaching competency on classroom processes and academic outcome. Learning and Instruction 21(1), 95–108.

Chingos, M. M. (2013). Class size and student outcomes: Research and policy implications. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 32(2), 411–438.

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Teacher quality and student achievement: A review of state policy evidence. Educational Policy Analysis Archives 8.

Dee, T., & West, M. (2011). The non-cognitive returns to class size. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 33(1), 23–46.

Dynarsky S., Hyman, J. M., and Schanzenbach, D. W. (2013). Experimental evidence on the effect of childhood investments on postsecondary attainment and degree completion. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 32(4), 692–717.

Finn, J. D., & Achilles, C. M. (1999). Tennessee’s class size study: Findings, implications, misconceptions. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 21(2), 97–109.

Fleming, R., Toutant, T., & Raptis, H. (2002). Class size and effects: A review. Bloomington, IN: Phi Delta Kappa Educational Foundation.

Guarino, C. M., Santibañez, L., & Daley, G. A. (2006). Teacher recruitment and retention: A review of the recent empirical literature. Review of Educational Research 76(2), 173–208.

Horning, Alice. (2007). The Definitive Article on Class Size. WPA: Writing Program Administration 31(1/2), 14-34.

Kelly, J., & Scafidi, J. (2013). More Than Scores: An Analysis of How and Why Parents Choose Schools. Friedman Foundation for Educational Choice. Retrieved from https://www.edchoice.org/research/more-than-scores/ [1]

Krueger, A. B. (2003). Economic considerations and class size. The Economic Journal 113 (485), F34–F63.

Rich, M. (2013, December 21). Subtract teachers, add pupils: Math of today’s jammed schools. The New York Times. Retrieved from http://www.nytimes.com/2013/12/22/education/subtract-teachers-add-pupils-math-of-todays-jammed-schools.html [2]

This position statement may be printed, copied, and disseminated without permission from NCTE.