Executive Summary

To learn directly from teachers about the impact of literacy assessment in the classroom, the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE) Assessment Task Force designed a five-question online survey, the Assessment Story Project.

A total of 530 teachers responded to the survey. The sample, while not statistically representative, included a wide range of teachers from elementary grades through college teaching in urban, suburban, and rural areas. We reviewed and analyzed the survey responses, looking for patterns both within and across educational levels. In all analyses, we found strong patterns representing the majority of responses, although, as we report in more detail later, there were also distinctive minority views.

Five main themes about writing and reading assessments emerged from the survey responses:

- Teachers are knowledgeable about assessment practices. They reported using many different methods and approaches to evaluate students’ work for both summative and formative purposes.

- Teachers value meaningful reading and writing assessment, which they define as assessment that supports teaching and learning.

- Teachers find that standardized, mandated reading and writing assessments are often not meaningful. A minority of respondents acknowledged the potential benefits that some standardized assessments could offer.

- Teachers and students experience high-stakes assessments as detrimental, in part because of their impact on student learning and in part because of the resources they divert from more useful activities.

- Teachers offered valuable insights about alternative approaches to assessment, both in the classroom and system-wide. From the responses, several principles emerged about what meaningful assessment should do, including engaging students in real-world tasks; employing tasks calling for students to be creative problem solvers; tapping classroom work that students are already engaged in, using “embedded” assessment; including students in presenting to others: administrators, parents, and community members; and providing for feedback that can be used during the school year by both teacher and students to support learning.

Introduction

Assessment of student learning continues to occupy the center of discussions and decisions in and about education. Teachers, however, are rarely included in such conversations and policy decisions, despite the fact that, apart from the students who are the subjects of this activity, teachers have more experience with such assessments than do other stakeholders. After all, schools call on teachers to design and implement formative assessments and to administer standardized assessments, and in these processes, teachers experience the effects of high-stakes testing and witness the impact of assessments on students, colleagues, and schools. But to date, no research has inquired into what such activity looks like from a teacher’s perspective.

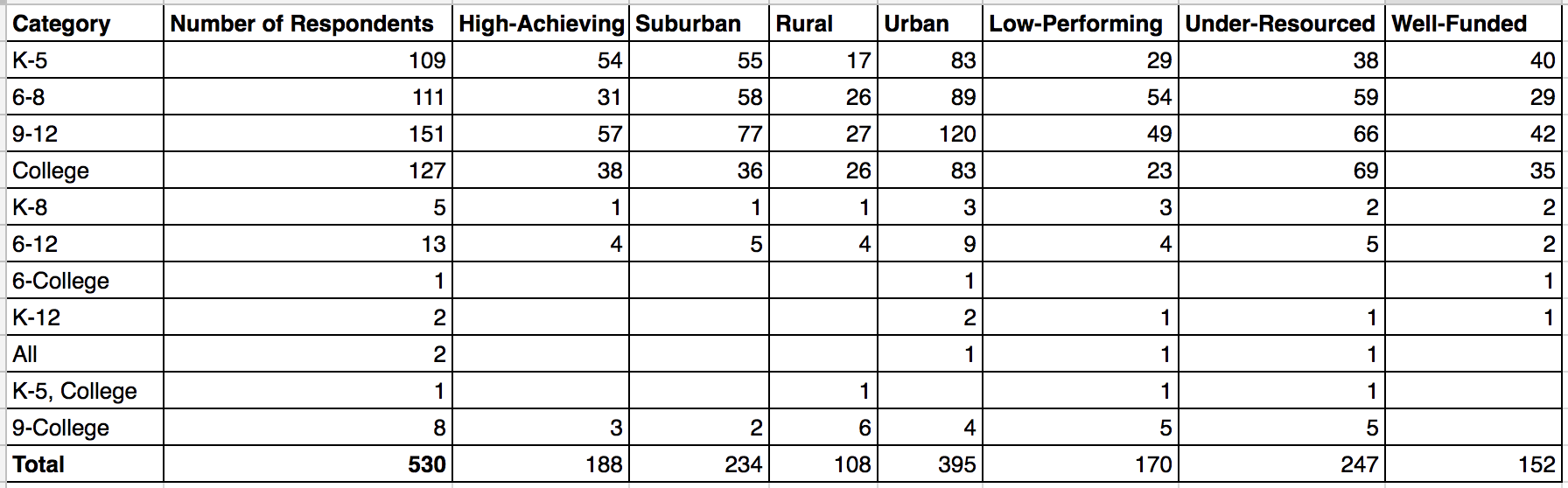

To learn about how literacy assessment actually operates in classrooms, the National Council of Teachers of English Assessment Task Force designed a five-question online survey titled the Assessment Story Project. Our intention in creating this survey was to learn directly from teachers about the impact of literacy assessments both on them and on their students and to learn about how teachers themselves design and use literacy assessments. Accordingly, the Assessment Story Project asked about mandated, standardized assessments as well as about the literacy assessments teachers themselves design. The survey, which is available in Appendix A, was open to educators from February to June 2015, with most survey questions open-ended to allow for fuller explanations and responses. As indicated in Appendix B, educators from all grade levels completed the survey.

Respondents: A total of 530 teachers responded to the survey. The sample, while not statistically representative, included a wide range of teachers from elementary grades through college teaching in urban, suburban, and rural areas. Respondents teach in well-funded and under-resourced schools as well as low-performing and high-achieving ones and represent both public and private institutions and most states. (Although participants were not asked to identify their schools geographically, or as private or public, many did so in their responses.) Respondents were not necessarily NCTE members, although NCTE media outlets, as well as other professional networks, were used to invite participants.

Data Analysis: We reviewed and analyzed the survey responses, looking for patterns both within and across educational levels (i.e., elementary, middle, high school, and college). In all analyses, we found strong patterns representing the majority of responses, although, as demonstrated in the following analysis, there were also distinctive minority views.

This report does not attempt to present all responses or the raw data gathered from the surveys. Instead, it articulates patterns in teacher responses and observations about how literacy assessment can both inform and inhibit students’ development as readers and writers.

What We Learned from Teachers about Literacy Assessment

Five main themes about writing and reading assessments emerged from the survey responses. Each theme is identified in the following list and supported by brief summaries and excerpts from the survey responses that illustrate or elaborate on the main idea.

1. Teachers are knowledgeable about assessment practices.

Three of the five survey questions asked teachers about their use of assessment in their classrooms. Responses demonstrated that regardless of the teacher’s level and type of institution, teachers regularly incorporate a variety of assessment approaches to support student learning.

“My assessment is constant, really. Within the time frame of the class itself, by observing [students’] group discussions, their responses during class discussion, I can draw some conclusions about their interpretation of a reading. I do much more daily assessment than anything else because I am able to make effective adjustments immediately. . . .” Jayme, college, under-resourced, rural

“I work with my students daily trying to have one one-on-one interaction with each of the 45 students who come to me. I talk with them, read what they have written and give feedback. This allows me to know each student as both a reader and writer. From this interaction I can change the focus of a small-group lesson or a whole-group lesson to suit the needs of the individuals. Planned lessons do not always offer the benefit that is assumed when writing the lesson plan. With many ELLs in my classes, it is important to find out what gaps they may have before expecting them to learn new information. Background knowledge is always key.” Anonymous, K–5, well-funded, high-achieving, suburban

“Daily classroom feedback, from exit slips to quizzes or entry activities, helps me keep tabs on students and communicate with each individual frequently.” Heather, college

“The most useful assessment is day-to-day formative that guides the next step in instruction. I wish summative assessments were better designed to be more appropriate for small children. Those tests are too long and we put so much emphasis on them that students are intimidated.” Sharon, K–5, under-resourced, rural

“I use running records daily as a type of formative assessment (which can be used summatively from time to time as well). Running records inform me of my students’ growing competencies in how well they are processing texts and what kinds of behaviors they are exhibiting. Some behaviors are praiseworthy, meaning they are good and are reinforced; others are promising, meaning they show that the student is trying to do something productive; and other behaviors observed are not helpful or are missing and need to be taught. Daily analysis tells me about fluency, comprehension, use of sources of information, and strategic behaviors, which inform upcoming decisions about what to teach next in order to move the student forward.” Jeff, K–5, well-funded, high-achieving, suburban

“Everything I do in class is a form of assessment: class discussions, small-group discussions, one-on-one conversations with students, informal writing assignments, formal essays. Students are constantly being assessed and I’m constantly updating my understanding of their progress.” Elizabeth, 9–12, under-resourced, low-performing, urban

Teachers also reported using many different methods and approaches to evaluate students for both summative and formative purposes, including mandated and teacher-selected assessment tools and strategies. Likewise, teachers observed that they practice assessment on a weekly, if not daily, basis. Collectively, responses indicated that teachers understand and appreciate the ways that formative assessment supports writing and reading development.

“Formative assessments just make the most sense in a writing classroom. The point is to get better—and experienced writers know that most of that happens in revision.” Bill, college, under-resourced, high-achieving, rural

“I assess learning in a writing class by reading students’ writing in drafts, commenting on strengths and weaknesses, and then grading the final copy. When I read drafts, I can see what students understand and what they don’t understand, and I help them learn through comments on drafts, consultations in my office, and comments and a grading sheet on a final paper.” Anonymous, college, well-funded, high-achieving, suburban

“The most common way I assess students is through formative assessments. I assess students before a unit to see where they are, I then base my unit on teaching the skills they need, and put students together who have similar needs and teach them in small groups. As students work, I work with my small groups (which change as students’ needs change) and individuals. I assess students by talking to them and examining their work. This is a continuous process of assessing and instructing students based on their needs.” Lisa, K–5, well-funded, high-achieving, suburban

“Formative assessment revolutionized my classroom! I use it for assessing all my skills now in lieu of most paper tests! For example, when studying plot structure, I place my students into small groups; then my clipboard and I move throughout the class listening to the interaction in each group. The moment I knew this form of assessment was the answer I was looking for was when I heard two students, two underperforming, disinterested students, debating over which part of the story would best fit the criteria for the climax! Within a matter of minutes I could determine whether these students understood the elements of plot! No worksheet was necessary! Formative assessments allow me to steer students’ answers in the correct direction if they begin to struggle with their task. I can facilitate without driving the results! Formative assessment allows me to pin down more precisely the areas of instruction I need to focus on more intensively as opposed to those skills and concepts students have mastered or are on their way to master!” Jill, K–5, under-resourced, high-achieving, low-performing, urban

“Formative assessment shows both myself and my students not only where they currently are but also where they have grown from. This can be motivating and rewarding, or it can provide a needed nudge for a student to apply themselves. Either way, formative assessment, when including the students, helps the students take more responsibility for their own learning goals and growth.” Anonymous, K–5, high-achieving, urba

“It’s not uncommon for me to see a common weakness amongst students while I’m circulating [among the students], which causes me to stop the class and teach a mini-lesson to address that weakness. This keeps learning timely and personal.” Elizabeth, 9–12, under-resourced, low-performing, urba

“I use formative assessments and informal observations, as well as data from [XXX] testing, to help guide my planning for whole-group instruction and small-group conferencing. Reading 1:1 helps so much because I use miscue analysis through running records. It helps me plan differentiated literacy centers.” Nancy, K–5, under-resourced, urban

“I use all kinds of assessments: rubrics for writing and projects, paper-and-pencil for facts, observations and conferencing, running records, oral assessment, and of course the dreaded [XXX] test. I use all of it to drive my instruction, but my preference for literacy is observation, conferencing, and running records. These assessments are immediate, personal, and targeted. If I notice someone having trouble decoding digraphs, then the next day’s work addresses that. The child in question gets exactly what he needs in the moment that he needs it.” Julie, K–5, under-resourced, high-achieving, low-performing, rural

“I use a published letter-sound assessment, a state-mandated phonemic awareness [assessment], and a teacher-created observational checklist for segmenting sounds and using Elknonin boxes to fine-tune and focus on specific areas that may be difficult for a child and to help me make inferences about how a student is processing language in order to change my presentation of materials to help a child move forward with their reading and writing. Do they know sounds? Can they sequence sounds? Can they segment sounds? Can they blend sounds? Do they understand first, middle, and last in CVC [consonant-vowel-consonant] words? Do they lack confidence? Do they see a purpose or are they motivated to read or write?” Anonymous, K–5, well-funded, low-performing, suburban

“I try to use as many pieces of the puzzle as I can gather and find. Student and parent surveys, developmental continuum assessments of reading and writing, as well as normed standardized test results are looked at together. Though it takes time to gather all this, it is well worth it in terms of the growth it helps me move my students toward.” Anonymous, 6–8, suburban

2. Teachers value meaningful reading and writing assessment, which they define as assessment that supports teaching and learning.

Respondents, representing all educational levels, identified multiple assessment activities they employ to support students’ literacy development, including classroom observations of students, exit slips, informal writings, and one-to-one conferences. While most specific examples involved teacher-designed formative assessments, some respondents also expressed value in standardized assessments when used as part of a formative and/or low-stakes assessment approach.

“In teaching a course in basic essay writing I used a standardized test of grammar and mechanics to help determine whether students had knowledge of writing rules and conventions. Using this in conjunction with evaluations of their writing and revision work helped me pinpoint the source of difficulties in their reading and writing.” Anonymous, college, under-resourced, high-achieving, rural

“I use a variety of assessments on a daily basis. I teach mini-lessons to introduce reading skills and strategies and then the students practice by reading alone or with a partner. I circulate around the room and take notes by listening to them read and having a conference about what they are doing. I also assess how they are doing through written responses which can be in the form of a paragraph, oral retelling, graphic organizers, and illustrations. The students have a portfolio where all work is kept, and I have them periodically self-evaluate their work and set goals. I also have them give me feedback regularly on what worked that day or didn’t work. I also have them help me come up with ideas when I’m modeling a lesson b/c it shows me if they are getting the concept or not.” Cassandra, K–5, high-achieving

“I understand the need for standardized tests, to a degree, but we also can’t test our kids to death. Assessment results in student learning through the assessment process, while testing is just that—testing.” Anne, 9–12, urban

“Formative assessments help me evaluate how well the concepts were understood. These are immediate and help me adjust in the moment. Exit slips help me adjust lessons for the following day or the next lesson. Standardized district assessments help me see where the students are in relation to others and allow me [to] focus on students who may need more attention.” Anonymous, K–5, well-funded, high-achieving, suburban

“One example of informal formative assessment that I do in my fifth-grade class occurs during interactive read-alouds. I consciously note who asks questions, who makes inferences, whose inferences are grounded on evidence from the text, who is able to access prior knowledge to deepen understanding, who is able to build an understanding of main idea (informational text) or theme (fiction), and who has difficulty with any of these aspects of comprehension. I’m able to follow up on this in conferences with individuals during independent reading time, as well as in small-group literature circles. When we have literature circles, each student has a journal in which topics that the student would like to discuss are written. Additionally, each journal has notes on whatever literary element (conflict, plot structure, character development, etc.) we’re investigating. These journals are useful formative assessments that help me in my work of facilitating discussions that will deepen students’ understanding of literature. Conferring with individuals during independent reading time is also useful, giving me a moment to do on-the-spot teaching as well as informal assessment.” Karen, K–5, well-funded, rural

“Recently I have come to appreciate the power of Socratic Seminar as a way to assess students’ understanding of a variety of types of text, as well as their ability to use evidence to craft a response to a question and to engage in high-level dialogue with their classmates about themes, author’s craft, and other elements of text. This powerful discussion tool is an excellent way for me to assess my students’ learning in multiple ways: speaking, listening, reading, and writing. It also informs instruction, as I use my formative assessments to plan further instruction.” Cecilia, 6–8, well-funded, high-achieving, suburban

3. Teachers found that standardized, mandated reading and writing assessments are often not meaningful.

Teachers identified many ways that standardized, mandated reading and writing assessments undercut their effectiveness as teachers and limited students’ opportunities to learn. In particular, teachers expressed frustration with (1) the mismatch between students’ performance in class and on standardized reading and writing assessments and (2) the lack of timely, informed communication about assessments, especially because of its impact on teachers’ effectiveness and student learning.

“I use observation of center work as an assessment. It is especially useful in my kindergarten classroom because I am able to really see the students’ methods of approaching a task and have a discussion with them if I am in need of more information. I find it to be the most practical and effective assessment in kindergarten. Any other form of assessment takes a lot of time away from instruction and sets the stage for behavioral issues.” Lisa, K–5, low-performing, suburban

“The data is valuable. The issue comes in devoting the time it takes to mine the data and analyze it. If school leadership does not have supports in place, then data is viewed as an extra step or an obstacle. In that sense, it undermines the power of the data.” Kelli, 9–12, under-resourced, urban

“It [standardized measures] usually undermines [learning] in that it might show a poor performance by a student who is actually a thoughtful and thorough reader. The student might not answer questions well, but if they were to sit and discuss their book they would do well. Data from standardized tests always follows the same pattern: students struggle with main idea and theme at 5th grade. Well, maybe it is the way the questions are worded. Baseline, formative, summative, observation, direct, high stakes (for both teacher and student), online performance with downloaded remediation packets for tutoring. The assessments both online and baseline help me drive differentiated instruction, so there is growth by summative. High stakes gives me little to work with at this point because data tools are too time consuming to use, and there is no bank of questions to support needs for each student at my fingertips.” Anonymous, K–5, under-resourced, high-achieving, urban

“Short assessments with data that is usable for teachers would be helpful. The data that we get back from the standardized tests is NOT useful because of the curve, cut scores, etc. Those calculations take away from the ability of a teacher/parent to help a child improve.” Anonymous, 6–8, low-performing, suburban

“At our institution, we are forced to give our students standardized tests. While students performed below the national average on the in-class, timed essays, the same students had excelled in our localized curricular assessment.” Anonymous, college, under-resourced, urban

“Formative assessments help drive the instruction in my school. Children respond to the variety of formative assessments used. Some children respond better to verbal prompts and discussions whereas others prefer writing tasks. Still others prefer demonstrations, etc. Standardized testing diminishes students’ motivation to complete tasks to the best of their ability and makes them feel like the test, not learning, is what’s important. In addition, they often feel anxious and incompetent.” Jeanette, K–5, high-achieving, suburban

“I communicate informally via a detailed webpage and email blasts. And formally with a back to school night presentation, two conferences a year, and detailed report card comments three times a year. The informal communication is much more timely and valuable.” Margaret, K–5, well-funded, high-achieving, suburban

“Performance assessments, reading response, running records. The standardized tests have never been timely enough; the children are in the next grade so they don’t really have impact. The only thing I haven’t liked is when kids are rewarded for their perfect standardized tests in our district.” Kim, K–5, well-funded, high-achieving, suburban

“I give comprehension tests, and I also have students do writing projects that help me understand what they understand. Unfortunately, I have to give so many tests from the district that I don’t really want to give them any more of my own.” Judy, 6–8, under-resourced, low-performing, urban

While the majority of teachers did not find value in required standardized reading and writing assessments, some respondents acknowledged the potential benefits that some standardized assessments offer. For example, some teachers explained how results from a standardized test helped them interpret a student’s classroom performance or provided additional information to guide their teaching. Some elementary teachers commented on the value of routine benchmark testing or progress monitoring to help them adjust instruction.

“A test has not undermined anything for me. I just often look at data and put it in a folder because it’s not useful. AP [Advanced Placement] scores, however, have helped me to gauge how I need to adjust my focus in certain areas. The AP Language exam encompasses so many higher-order skills that I actually don’t mind using that kind of standardized data to drive my instruction.” Paul, 9–12, suburban

“At times, when I’ve had a student who turned in really poor work and/or wouldn’t participate in class, I’d check verbal scores on SATs to see if that number in any way related to the type of writing I was seeing.” Anonymous, college, rural

“ . . . I learn from their standardized test work of how I might modify my instruction for future students.” Ted, college, under-resourced, urban

“(A) Our district uses benchmark assessments to get the reading level of the students. We assess the below-grade-level students 3 times a year. This assessment is done individually and takes about a half an hour per student. . . . This trimester I have 16 benchmarks to do . . . meaning at least eight hours away from reading group instruction. (B) The benchmark we use not only gives us the instructional level of each student, it shows the strength or weakness in fluency and comprehension. I can see the word attack strategy each child uses so I can group the students with common needs.” Maeie, K–5, under-resourced, low-performing, urban

4. Teachers and students experience high-stakes assessments as detrimental, in part because of their impact on student learning and in part because of the resources they divert from more useful activities.

Teachers indicated that when assessments are high stakes—or perceived as high stakes—the potential value of them is undermined. Such detrimental consequences, experienced by teachers and students, can be emotional as well as educational, affecting performance on the assessment as well as future learning.

“Children are ‘assessed’ every day, every week. PLCs [professional learning communities] are really about raising test scores and not about best practices. We are meetinged to death. Constant discussions and pressure about test scores. Teachers cry. They are competitive in a fully unhealthy manner. Black and brown children are treated differently when it comes to gifted and talented identification. We have many Hispanic students who struggle and are also tested ad nauseam for a whole buffet of purposes. Our state is heavy on [major assessment publisher] spending. We still use the antiquated [company-produced curriculum materials] crap! The state’s education is in an unholy mess.” Mary, K–5, low-performing, suburban

“Low-stakes writing works well for me. If my students realize from the beginning that I am looking for understanding, not just trying to ‘get’ them with grades, then the vast majority will be more willing to answer the formative question or questions.” Kathy, 9–12, under-resourced, low-performing, rural

Teachers are frustrated that students are placed into remedial classes or mandatory tutoring on the basis of standardized test results—in some cases, on a single test score—that don’t adequately represent students’ abilities. When this happens, students may lose educational opportunities. For example, high school students may lose opportunities to take college preparatory or elective courses or certification programs. College students may be required to take remedial, noncredit courses that delay or impede graduation.

“My districts often use mock tests that are supposed to imitate the state exam. These tests are slapped together by the district office and are not checked for reliability or validity. However, these exams are used to place students in mandatory tutoring. (Even though subjects tested were not necessarily covered in class yet.) Admin relied more on these test scores than teacher observation and assessments. Thus placing many students in tutoring who didn’t need to be there.” Chanel, 9–12

“The [XXX] Reading Assessment has pigeonholed many of my students as struggling readers, when they are not. Years of stress over this exam causes them to believe that they cannot read and snowballs into general academic failure. Approximately 10% of my level 1 and 2 readers are actually reading below grade level.” James, 9–12, well-funded, high-achieving, suburban

“We use the [XXX] exam, an [XXX] product, to place students who have not taken the ACT or SAT into an appropriate math/reading/English course. I would say that the exam gets the student placement in English wrong about 30% (very rough estimate) [of the] time. Our process is more cattle-through-the-chute than individualized, and this means that some students will spend semesters in developmental prison unnecessarily, and others will be over their heads in a comp 1 class. The standardized test alone approach is economical, but not accurate, and it undermines our overall educational process.” Mike, college

“One adult English learner scored 43% on a standardized and another scored 47%. Based partly on these test scores, they were placed into the same class, but there was a huge difference in their actual English levels. One was a true beginner (the 43% score) who needed a course at a much lower level and had great difficulty reading and writing without translation software. Even a dictionary was often not enough. The other was a false beginner, quite comfortable speaking and listening, but in need of help with writing.” Cyndi, college, urban

According to respondents, educational resources—including money, time, and energy—that are devoted to high-stakes assessment could be more productively used for activities that promote effective teaching and learning. Teachers reported, for example, that the time devoted to preparation for and administration of these tests could not be dedicated to teaching or administering more informative classroom-based assessments. In some K–12 schools, the increasing use of computers for testing has resulted in significantly reduced access to computers for learning during long stretches of test administration.

“I am an early childhood literacy consultant, working mainly in the area of helping teachers implement inquiry-based projects. For the past 6 years I’ve done work in a school in NYC’s Lower East Side. The school population is mainly ELL learners with many special education children. It is a public school. There is one kindergarten teacher who I particularly enjoy working with. She is energetic, smart, organized, and eager to do all that she can to create the best learning environment for her children. We’ve worked on strategies for implementing observations and assessments that are useful for planning next instructional steps. This year the principal and I both noticed that the teacher seemed less smiley, less energetic, and less enthusiastic. I met with the teacher to discuss this with her. She told me that she had so many assessments to do for the children in her class that she has practically no instructional time, no time to implement the wonderful inquiry projects that they have been doing the past few years, and, truthfully, no time to enjoy her teaching. As soon as she is finished with one assessment, it’s time to do running records. These assessments give her much less information than she was getting when she had time to spend with the children and understand their interests, learning styles, and learning frustrations. When she had these observations, she was able to plan appropriate activities and interventions. We’ve spent time learning how to collect work for portfolios, but, she told me, there’s not much time for the children to actually do the work that would go into these portfolios. This is kindergarten. KINDERgarten! How misguided can the education world get?” Renee, K–5, under-resourced, urban

“National testing is an unnecessary, money-making venture that provides NO usable data for classroom teachers. It is punitive for students as well as teachers.” Anonymous, K–5, under-resourced, low-performing, suburban

“I wonder what education would look like in this country if we had districts in charge of their own assessment plan. Students could take one standardized test in high school—like Finland. The money saved could be poured into districts for curriculum and professional development, among other things. I think gains could be huge.” Katherine, K–5, rural

“Too many assessments—state and federally mandated—need something that addresses the CCSS [Common Core State Standards]. Why can’t SBAC [Smarter Balanced Assessment Consortium] performance test be used every 3-4 years for cumulative look at progress (not every year) and reduce cost as well as number of days spent on mind-numbing assessments that detract from learning opportunities?” Anonymous, K–5, under-resourced, low-performing, rural

5. Teachers offered valuable insights about alternative approaches to assessment, both in the classroom and system-wide.

When asked to provide ideas for ways “other than standardized tests . . . to ensure that all students across all districts are succeeding and that schools have the data they need to improve,” teachers across the educational spectrum identified multiple kinds of assessments. Many of these suggestions, such as portfolios, projects, and presentations, support learning through formative assessment while contributing to a summative assessment. In fact, many teachers reported that portfolios, projects, and presentations, used together, already function as an assessment system.

“The most useful assessment is day-to-day formative that guides the next step in instruction. I wish summative assessments were better designed to be more appropriate for small children. Those tests are too long and we put so much emphasis on them that students are intimidated.” Sharon, K–5, under-resourced, rural

“Short assessments with data that is usable for teachers would be helpful. The data that we get back from the standardized tests is NOT useful because of the curve, cut scores, etc. Those calculations take away from the ability of a teacher/parent to help a child improve.” Anonymous, 6–8, low-performing, suburban

“I don’t think standardized tests should take place every year; trust teachers to know when students aren’t meeting expectations—we know our kids. Instead [we should test] twice in elementary, once in middle and high. It could be linked to passing the grade, so students have buy-in, and scores w/o student buy-in should NOT be linked to teacher ‘effectiveness’. . . . A portfolio system would probably be most genuine for these reasons, where students are required to submit three pieces (narrative, explanatory, and argumentative) with drafts and revisions so reviewers can see the entire process and everyone is familiar with the grading rubric.” Casey, 9–12, well-funded, low-performing, suburban

“Such assessments need to include a wide range of methods—not just high-stakes. Classroom observations, representative student work (especially long-term writing projects!), teacher gradebooks, discipline records, student interviews, and more. I would call this something like ‘wrap-around’ assessment. It would be very complicated and involved, but might come closer to providing a true picture of what is happening in a school and why students are or are not learning.” Anonymous, 9–12

“. . . I see the downsides of standardized testing with each group of first-year students that comes in the door, as they look at reading and writing overwhelmingly as a means of testing.” Anonymous, college, well-funded

“I would love to see a K–12 portfolio type of assessment adopted where samples of a student’s literacy tasks are collected over the course of his education. Of course, the products could be reviewed periodically to inform teachers of their instructional moves based on what students have mastered or have yet to master. This would be more indicative of his growth than a timed aptitude test.” Rosalyn, 9–12, urban

“I always conclude a literature study with two large assessments: one, a test, with matching, multiple choice, and short answer; the other, an alternative assessment, such as a group project, or an individual essay written using the writing process of drafts, peer response, and revision. In this way, students are not only reading and learning, but they are doing so as part of a community of learners who are learning as well to hold intelligent, civil, thoughtful conversations on serious subjects.” Valarie, 6–8, under-resourced, high-achieving, rural

“I would endorse state-wide portfolio as a type of alternative assessment. If states were to identify artifacts at each grade level (aligned to state standards) and develop common rubrics for scoring, this might be a powerful supplement to standardized tests. I would like to see students use this portfolio to present to a local committee (teachers, peers, community members, administrators) as a means of closing their K–12 education and a means of reflecting personally and professionally on what they have learned.” Anonymous, 9–12

“The government and leading organizations like NCTE should promote standards of assessment creation, which local schools are accountable for enforcing. Assessment design is an intimate process. The farther you remove the designer from the practitioner, the more likely the two will have a misunderstanding.” Jen, 9–12, under-resourced, high-achieving, suburban

Taken together, such alternative assessments are characterized by a set of assessment design principles: assessment should

- Engage students in real-world tasks

- Employ tasks calling for students to be creative problem solvers

- Tap classroom work that students are already engaged in, using “embedded” assessment

- Include students presenting to others: administrators, parents, and community members

- Provide for feedback that can be used during the school year by both teacher and student to support learning

Based on teachers’ ideas for alternatives to standardized assessments, several questions are raised:

- What do mandated, external assessments add to the assessment systems teachers already have in place?

- If external assessments continue to be required by law, is there a way to consider them alongside of the assessments teachers are already using?

- When mandated assessments fail—placing students in remediation or intervention programs that aren’t needed, or failing to appropriately place students who did need tutoring—where is the redress? What challenge is built into the model of external assessment?

Recommendations

Based on the analysis of the teacher responses to the Assessment Story Project, we reached two important conclusions: (1) teachers are essential to the literacy assessment process, yet their voices are not being heard in the design, development, and implementation of assessment systems; and (2) many teachers already have multifaceted, effective assessments in place that make many of the externally mandated, standardized assessments unnecessary.

With these conclusions in mind, we urge policymakers and educational leaders to follow two recommendations as implementation of the Every Student Succeeds Act begins:

First, effective literacy assessment begins with teachers’ expertise and experience.

Assessment systems are more likely to affect classroom instruction and student learning positively when teachers have a variety of opportunities to actively participate in the assessment systems that will affect their students, from the start of the discussion through the development of the assessments. Teachers understand that assessment—both formative and summative—is an essential component of learning. They report using assessment on a daily basis to inform their teaching and to plan for future learning. Because of their expertise and experience, teachers bring a perspective to assessment that is not available to policymakers and test developers.

Second, teachers need to be primary participants in literacy assessment development. Teachers should be included in all decisions governing literacy assessment. By including teachers throughout the development of assessments, test developers can respond responsibly to teacher voices and create an improved assessment. Teachers have a unique classroom perspective: they know their students, they want to promote learning, and they are committed to students’ achievement. Effective assessment practices that support student learning begin with this perspective.

Acknowledgements

We extend our gratitude to the teachers who made time to share their experiences and insights. Their contributions have affirmed our commitment to including teachers’ voices in the ongoing discussions of assessment.

Appendixes

Appendix A: Assessment Story Project Survey

- Assessing learning is something teachers do daily as they strive to meet the needs of their students. Teachers use many forms of assessment and employ many different terms to describe it, including formative assessment, classroom assessments, direct assessments, daily assessment, summative assessment, high-stakes assessment, multiple-choice tests, standardized tests, exit slips, and portfolios—in addition to many others. Please share an example of (a) how you as a classroom teacher use assessment to evaluate your students’ literacy learning and (b) how this use of assessment helps you teach more effectively.Please check all the following assessments that you use in your teaching:

o Classroom

o Formative

o High-stakes

o Summative

o Exit slips

o Standardized

o Daily

o Multiple choice

o Portfolios

o Other: - Choose one kind of assessment above that you find especially useful as a classroom teacher and explain how it is useful to you and/or your students.

- How might families and other community members be informed about assessment and involved in decision making around assessment? If you and/or your school already engage in such practices, please tell us about that as well.

- What assessments—other than standardized tests—might we design to ensure that all students across all districts are succeeding and that schools have the data they need to improve? In your view, what might such an alternative assessment be, and how might/does it work?

- Please tell us about a time when the results of a standardized test EITHER undermined OR enhanced the information you had gained through other types of assessments.

Appendix B: Respondents Reported Demographic Information

Released on August 23, 2016

NCTE Assessment Task Force

Chair:

Kathleen Blake Yancey, Florida State University

Members:

Scott Filkins, Central High School,Champaign, IL

Elizabeth Jaeger, University of Arizona (through October 2015)

Peggy O’Neill, Loyola University Maryland

Kathryn Mitchell Pierce, Saint Louis University

Lisa Scherff, Cypress Lake High School, FL

Franki Sibberson, Dublin City Schools, OH (joined October 2015)