This post was written by NCTE member Cheryl Hogue Smith.

In a recent article for TETYC, I described my attempts to overcome my insecurities and fears about writing (as best I can) and to find ways to improve the fraught relationship many of my students have with their writing. I deliberately focused this article on the experience of writing—with a secondary focus on the value of multimodal assignments in the classroom—because I wanted to show that “academic writing” doesn’t need to be so narrowly defined. I wanted to discuss the importance of helping students find the same kind of courage I had to find because with that courage come the victories that allow them to experience how it feels to succeed–the victories that can lead to the fun and joy of writing. Here, however, I want to focus on the section that outlines the value of that particular multimodal assignment.

Creative Freedom in First-Year Composition

Obviously, I am not the first person to talk about creativity in the classroom. Patrick Sullivan argues that students should be both critical and creative thinkers and that teachers need to foster creativity with assignments that will prevent students from producing the kinds of perfunctory writing that derives from instruction that focuses on sentence-level error and five-paragraph formats that yield clichéd, surface-level thinking (29). Add to this the fact that many community college students have regularly been told they are not strong writers, often because their writing doesn’t conform to racially unjust notions of what language should be or look like, and it’s not difficult to see that their past academic experiences led them to develop counterproductive reading and writing habits that work against their success as students (Smith). Using my understanding of their fears and successes and understanding well that creativity can give students a freedom beyond traditional academic norms, I decided to convert a second traditional academic assignment in my first-year composition class into a multimodal project. Doing so meant that two of my three assignments were now going to tap into students’ creativity. With any luck, the two assignments combined would help students see themselves as strong and capable thinkers and writers and would provide the same kind of breakthrough with their own relationship with writing that I had experienced with mine.

I should explain that I teach in Brooklyn at Kingsborough Community College of the City University of New York in a Learning Communities Program whereby my first-year composition course is “linked” with an art history survey course taught by a different instructor. My students are entering freshmen, taking first-year composition in their first semester at Kingsborough, and are full-time students often working full-time or at least several hours part-time, usually traveling on public transportation to and from school for one-to-two hours each way. Many also have extensive family obligations, are food and/or housing insecure, and often deal with life circumstances that understandably interfere with or take precedence over their learning.

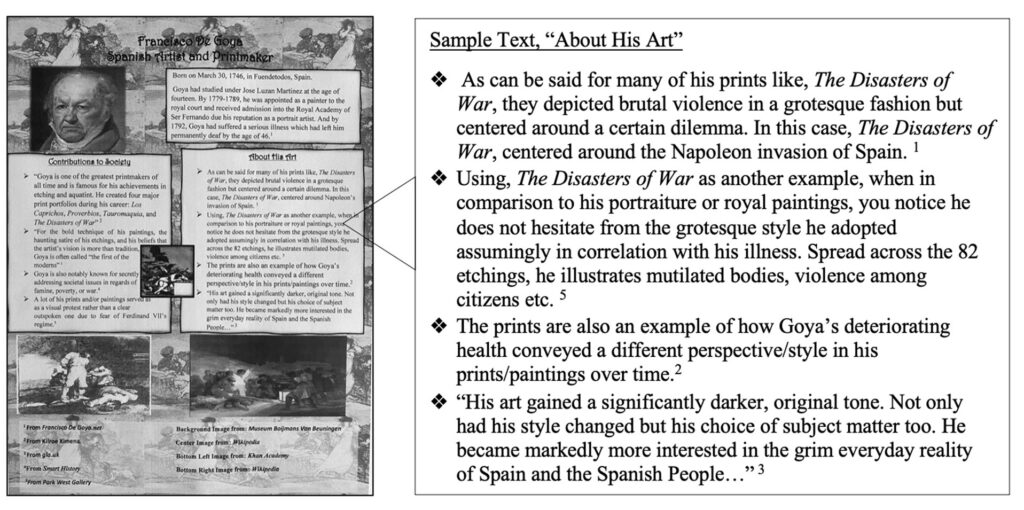

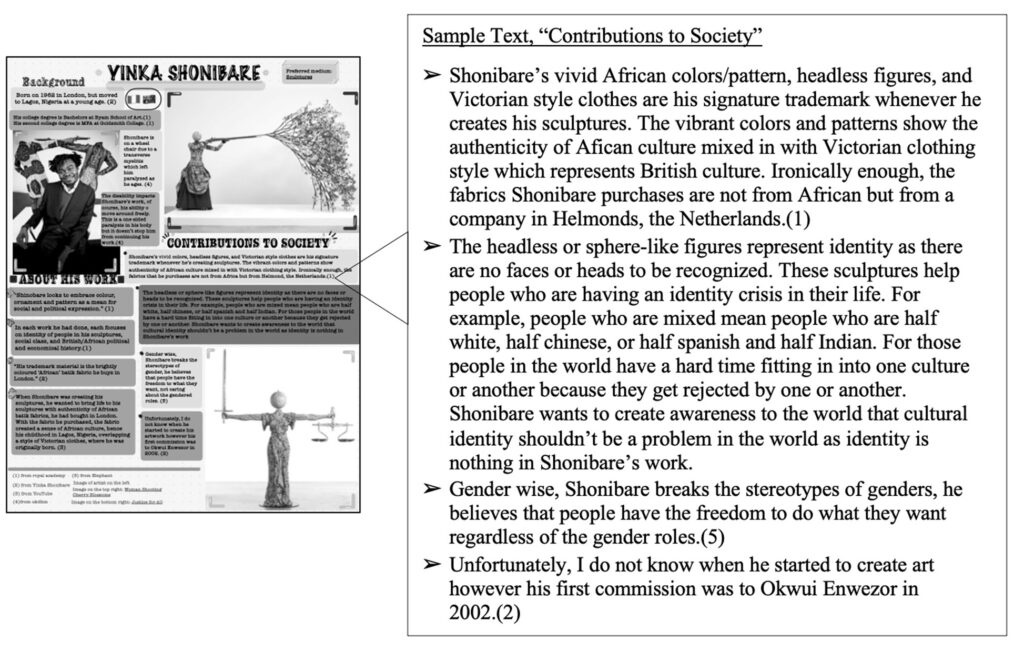

My overarching theme in the course is “protest art,” and the first assignment asks students to find a piece of art online and discuss how it could be seen as both protest art and propaganda (in a negative way), depending on who is looking at it. The final, third project asks students to create a video using images, music, and text to teach their audience about one artist’s contributions to the art world and that artist’s efforts to make the world a more equitable and just place. To prepare students for this third project, I converted the second assignment from a traditional argument essay to a one-page 8½ x 11 flyer that identified the most important information about the work and contributions of one visual artist. To complete this one-page project, I instructed students to do the following:

- Include images of artwork.

- Divide the flyer into sections with headings that represent a distinct topic or category; include information covering relevant background information about the artist, the artist’s medium, the importance of the work of the artist to any protest movements, and the influence the artist has had on other artists or on the art world at large.

- Use at least three different sources in each heading or section.

- Limit direct quotations to no more than half of the information.

- Use in total at least five sources.

I thought that the limit of one-page would challenge students to become discriminating about how many categories or headings they would create and what kind of information they would need to include or exclude in each. They also would have to be economical and thoughtful in constructing each section, avoiding repetitive or superfluous or irrelevant information, while taking care to consult multiple sources for accuracy and adequacy in reporting. In addition, I don’t grade students on language, and I hoped the untraditional nature of this assignment would help move those students who had learned to fixate on “error” away from a focus on language so they could learn to value their voices and learn to develop those voices without fear.

I include below two sample student1 Unit 2 flyers and one accompanying narrative excerpt for the Unit 3 project; all the below flyers are visually representative of what I received and show the range of development. (For color versions of four student flyers, plus my sample, please visit https://tinyurl.com/wyrdsamples.)

Despite the constraints I imposed on the assignment, students had the freedom to design their flyer in whatever way they wanted: I provided no rules about font, citation style (although they did need to include a separate Works Cited), color, margins, and so on, nor, again, did I grade on language. I was amazed with the final drafts: The flyer seemed to help students become more adept at paraphrasing and summarizing since at least half of the information they included needed to be composed in their own words. Moreover, the categories or topics they developed seemed to help them organize information for the Unit 3 narrative, where most seemed logically developed, well-informed, and reasonably comprehensive in scope. Their experience in composing their flyers also seemed to help students understand what it means to synthesize multiple sources; instead of writing one paragraph with several main ideas that used a single source, the paragraphs of their Unit 3 narratives tended to focus on one main idea fleshed out with information drawn from multiple sources. In the end, the flyers were beautiful, informative, and thorough and were evidence of having been created with joy.

Despite the constraints I imposed on the assignment, students had the freedom to design their flyer in whatever way they wanted: I provided no rules about font, citation style (although they did need to include a separate Works Cited), color, margins, and so on, nor, again, did I grade on language. I was amazed with the final drafts: The flyer seemed to help students become more adept at paraphrasing and summarizing since at least half of the information they included needed to be composed in their own words. Moreover, the categories or topics they developed seemed to help them organize information for the Unit 3 narrative, where most seemed logically developed, well-informed, and reasonably comprehensive in scope. Their experience in composing their flyers also seemed to help students understand what it means to synthesize multiple sources; instead of writing one paragraph with several main ideas that used a single source, the paragraphs of their Unit 3 narratives tended to focus on one main idea fleshed out with information drawn from multiple sources. In the end, the flyers were beautiful, informative, and thorough and were evidence of having been created with joy.

In an end-of-semester reflection, I asked students about their experiences with the flyer. The most typical responses I received were from students like Paul, who said, “I enjoyed the finished product. Feeling satisfied with what I had worked hard on.” And Lilac, who stated, “I had a fun time learning how to use google slides to create a flyer format. I also enjoyed reading articles and looking at the artist’s paintings.” And Marc, who adds, “Creating the Flyer at first was hard not gonna lie. Choosing the right layout, the design of the border, what type of font you wanted to use to make it look all pretty was a big hassle to me. But . . . it was a fun project to do.” Several remarked about the challenges of the assignment, like J, who said, “The most difficult part was to find and put together the three sources in each part.” And Amanda, who said, “It was somewhat difficult to use at least three sources per category for an assignment because it is hard to find the right details about the specific topic or person and to paraphrase the wording from the person I am getting the detail or information from instead of writing the original wording.” And Belle, who adds, “The flyer seemed a little intimidating at first because I have never done something like that or close to that. . . . Using multiple sources for one category got a little bit tough at certain points because a lot of the sources are saying the same thing, some are just saying it better than others. A lot of trial and error was also involved in order to figure out what sounded best.” But most students, when I asked if they would have preferred a traditional academic assignment over the flyer, admitted that, even though it was difficult, they still preferred the flyer. Kam, for example, said “I would prefer the project because it opens more creativity in your mind and helps with a lot of thinking and helps learn more about someone.” Belle adds, “I wouldn’t have rather had another essay because I feel like everything we have done in this semester, interconnected.” And J, who emphatically replied, “ABSOLUTLY NOT!”—a sentiment all but one student in three semesters agreed with. In the end, some of the best work I’ve seen in any first-year composition class has come from many of those flyers; I could see evidence of actual thinking in the way they categorized and included relevant information.

Notes

1 Student names are pseudonyms, and their work is used with their permission through an IRB process. I made no changes to any text or flyers.

Works Cited

Smith, Cheryl Hogue. “Interrogating Texts: From Deferent to Efferent and Aesthetic Reading Practices,” Journal of Basic Writing, vol. 31, no.1, 2012, pp. 59-79.

Sullivan, Patrick. “The UnEssay: Making Room for Creativity in the Composition Classroom.” College Composition and Communication, vol. 67, no. 1, 2015, pp. 6-34.

Cheryl Hogue Smith is a professor of English and WRAC Coordinator of Certification and Training at Kingsborough Community College of the City University of New York. She is a past chair of the Two-Year College English Association.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.