I refer to the summer reading text, Jamie Zeppa’s Beyond the Sky and the Earth: A Journey into Bhutan, a memoir about a Western woman’s experience teaching and living in Bhutan, and then ask students to go beyond the boundaries of “vacationer” to describe their most significant travel experiences. The resources and privileges available to these students are astounding as they describe hiking trips in Machu Picchu, surveying the breathtaking landscape from Mt. Kasyapa, or chatting with the locals in Japan. Drawing on their experiences, we construct our definition of travelers as people who immerse themselves in new worlds, never seeking to impose their beliefs on others but willingly adapting to the dominant culture. I prepare students to become travelers by embracing each work of literature as a new world and, instead of gravitating to the familiar or seeking to affirm their beliefs and values, to welcome discomfort as a means of changing and growing. We make a pact according to the words of The Dhammapada: “Travel only with thy equals or thy betters; if there are none, travel alone.”

Breaking with Tradition

In “Learning for Understanding: The Role of World Literature,” James D. Reese presents questions that inspired me to reform the secondary world literature curriculum: “What can we do in our classrooms to foster openness . . . ? How can we help our students become more aware of the world at large? How can we diminish harmful stereotyping . . . ? . . . Why teach world literature?” (63). World literature at the secondary level is usually a semester-long elective, featuring classic European texts or colonial literature alongside a few African or Hispanic options. Unfortunately, students remain within what is already comfortable, predictable, or familiar, and, ironically, they come away perceiving anything non-Western as “other.”

In the post-9/11 world, it is no longer sufficient for students to read literature that affirms their circumstance, values, or lifestyle. This generation is inundated with mixed messages by media on the threat of terror and the ideals of freedom. Desensitized by images of terrorists, natural disasters, suicide bombings, prison abuse, genocide, violent rallies, and war, their defense mechanism is blissful ignorance or jaded cynicism. Instead of passively looking at mirror images of their experiences, students must actively engage in looking through many and varied windows so they can make informed choices as global citizens. In fact, Peggy McIntosh addresses the consequences of a curriculum based only on mirrors: “My schooling gave me no training in seeing myself as an oppressor, as an unfairly advantaged person, or as a participant in a damaged culture. I was taught to see myself as an individual whose moral state depended on her individual moral will. My schooling followed the pattern . . . whites are taught to think of their lives as morally neutral, normative, and average, and also ideal, so that when we work to benefit others, this is seen as work that will allow ‘them’ to be more like ‘us’” (31). McIntosh’s concerns pose a direct challenge to teachers to ensure that students do not fall victim to a destructive pattern of ignorance and inadequacy.

In response to McIntosh’s challenge, I designed Global Voices, a yearlong world literature course, which offers seniors the opportunity to read award-winning, contemporary literature from Asia, Africa, South America, and Europe. In one year, students in my single section have grown tremendously in their ability to break the barriers of bias and discomfort to recognize the universality of the human condition. Our discussions have addressed and analyzed complex dynamics—politics, poverty, landscape, family, tradition, social class, childhood, prejudice, gender roles, and so on—as they develop and connect across time and cultures. The students’ oral and written responses to these issues are genuine, mature, empathetic, and certainly impassioned.

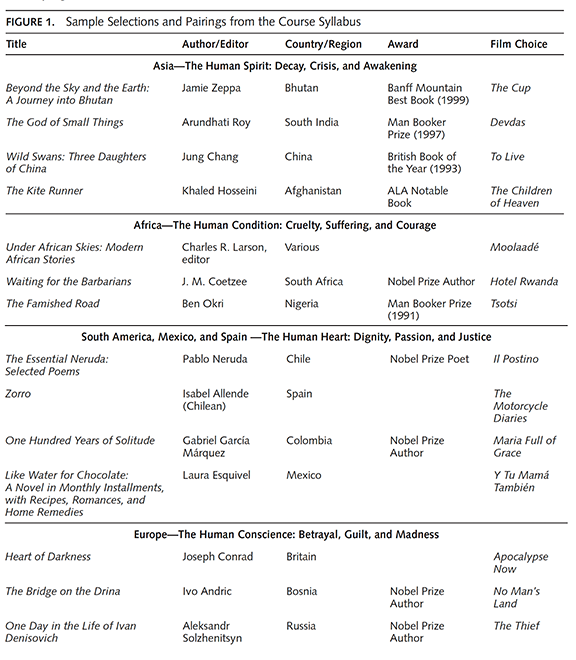

I decided that the most effective way to structure the course is to focus on one continent—Asia, Africa, South America, and Europe—each academic quarter, using a thematic approach to connect the various regions and literature. Since independent reading is a department requirement, I developed an annotated bibliography of Australian literature from which students would read one work each semester. Choosing from the vast collections of literature proved more difficult, so I established the following criteria for the course syllabus:

- Each text must represent a specific geographical region of Asia, Africa, South America, or Europe.

- Each text must be written by a writer native to that region or culture.

- Each text must explore contemporary issues concerning politics, landscape, family/relationships, economics, traditions, religion, and social constructs.

- Each text must be an award-winning or bestselling work of literature with strong reviews by reputable critics.

Zeppa’s memoir is the only text that does not meet the native writer requirement, but as a summer reading selection, it allows for an appropriate transition and introduces students to key themes and the various sensibilities of the traveler. The finished syllabus offers a fair representation of each continent through rich and compelling works of literature and allows for many dynamic and creative pairings (see fig. 1).

Since only three to four texts can be taught in a quarter, the remaining texts should be offered as independent reading options or rotated each year the course is taught. What is most important is that whether students are reading about the Orange-Drink Lemon-Drink man’s horrific transgression that traumatizes a child into silence in Roy’s The God of Small Things or Colonel Aureliano Buendia’s tender love for the young, poised Remedios in García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude, the literature will challenge students’ ability to remain ignorant or merely cynical.

To present this challenge in an appropriate context, Delane Bender-Slack asks students to respond to a central truth explored in world literature: “We are all humanists” (71). With the understanding that the term humanist refers to our concern for and interest in the welfare of humankind, her prompt certainly elicits thoughtful responses from students. However, since I wanted students to first explore different facets of humanity, I drew from the literature each quarter to highlight the following distinct cycles and forces that drive humankind:

- First Quarter/Asia—The Human Spirit: Decay, Crisis, and Awakening

- Second Quarter/Africa—The Human Condition: Cruelty, Suffering, and Courage

- Third Quarter/South America—The Human Heart: Dignity, Passion, and Justice

- Fourth Quarter/Europe—The Human Conscience: Betrayal, Guilt, and Madness

Although these themes may suggest a pessimistic approach to the literature, by evaluating debilitating social constructs students discover the enduring, haunting beauty—of the names, landscapes, dreams, traditions, and languages—that the writers so proudly capture underneath the pain. By the end of the year, students have explored the spiritual, physical, emotional, and mental implications of humane and inhumane acts across cultures. Only then can they successfully turn the mirror on themselves to evaluate their humanity and arrive at a set of universally valued human rights.

Awakening Hearts and Minds

Challenging students’ minds is difficult, but delving into students’ hearts is a more taxing endeavor that takes root in my beliefs, values, and experiences. As I review the reading for each day, I remain conscious of my emotional reactions, identifying passages that rouse my anger, cause confusion, or create an inexplicable and lasting impression. This forces me to dig deeper in the text, not to construct the essential question but to find it—and, without fail, it is always there. For example, after reading Ngugi wa Thiong’o’s “A Meeting in the Dark,” Tayeb Salih’s “A Handful of Dates,” Ken Saro-Wiwa’s “Africa Kills Her Sun,” and Sindiwe Magona’s “I’m Not Talking about That Now,” I questioned whether children are the perpetrators in or the victims of African society. Other times, the questions are more direct, such as, Why doesn’t Amir intervene when Hassan is being raped in Khalid Hosseini’s The Kite Runner? I hope to tackle these issues together, not in search of a finite answer but to reach a definite level of awareness.

It took considerable time and several guided discussions for students to name these difficult issues, much less share my sense of urgency to talk about them. Their initial reactions ranged from determined silence; a disengaged, “Well, as long as it doesn’t happen to me”; the incredulous “Is that a problem?” to the more pragmatic, “Well, sometimes you have to do X to get Y.” The more their eyes shifted away from mine, their bodies fidgeted or squirmed, or their expressions hardened, the more clearly I noticed that they were bothered. One student confided that this discomfort was reason enough to switch into Myth and Mind, a class I also teach, where he could explore cultures through mythology, fantasy, and epic tales. His natural impulse to escape is understandable; how many of us can witness the severe beating of an Untouchable or a father’s screams as he carries crushing loads of cement to provide for his family? I convinced him to stay, because envisioning ourselves as global citizens often begins with our ability to endure discomfort. Allowing students to close a book simply because the truth is too difficult to endure or too depressing only promotes bystander behavior.

Instead of accepting the burden of defending the validity and relevancy of these issues, I allowed the literature to teach and guide students from simply reacting to the literature to a more critical approach. We revisited the difficult passages and I urged students to examine the words and envision the images the authors so painstakingly and purposefully constructed to address the essential question. Soon, they outgrew my questions. When we discussed the scene in which the Orange-Drink Lemon-Drink man molests Estha in Roy’s The God of Small Things, the students were no longer satisfied with discussing right and wrong but willingly struggled to examine the nature of a repressive society and how it breeds people such as the Orange-Drink Lemon-Drink man or how the passage symbolizes the resentment of the lower class for the privileged class. Since then, students have raised such compelling questions or drawn such insightful comparisons that I have become a participant in their discussions. Judging from the quality of our discussions and their daily reading quizzes, I know they have read every work of literature this year from first page to last, and I am always impressed by how quickly they can find textual support for their ideas. Recently, one student wrote, “Whenever I think something is unfair or too difficult, I now remind myself how privileged I really am. The characters in these books have become my role models and have taught me a valuable lesson about optimism and resiliency.”

Creating Meaningful Experiences

Even as students approach texts critically from their hearts and minds, I also want them to address how the essential questions inform the traveler. Returning to the pact we made at the beginning of the year, I often set aside time to ask students to take stock of their travel experience. I am curious to know what risks they have taken, if they are enjoying the experience, and whether they are developing a sophisticated worldview. I have found that Pilot Guide Productions’ Globe Trekker series features strong role models in this respect. We have journeyed from the Yangtze River to Xia’n with host Justine Shapiro while reading Jung Chang’s Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China and dared the running of the bulls in Spain and traversed the Pilgrim Trail with host Shilpa Metha while reading Isabel Allende’s Zorro. Students like the candid simplicity as the host explorers interact with the locals, bravely try exotic food, and travel across every type of terrain.

I also use foreign films extensively throughout the year because doing so allows students to actively experience the text through a different medium, especially for those students who struggle to reconstruct such unfamiliar faces, landscapes, and images. It is important to note, however, that foreign films are certainly an acquired taste, especially as the expressive language, music, dance, and gestures can be quite new and sometimes uncomfortable. The class environment transforms, however, when a student struts in the next day singing the Chipi Chipi song from The Motorcycle Diaries.

This enthusiasm inspires me to keep creating different ways for students to connect with the literature. After reading The Kite Runner and J. M. Coetzee’s Waiting for the Barbarians, which deal with the victim/perpetrator/bystander dynamic, I assigned a narrative essay for students to explore one of those roles and to read to the class. At first, students were intimidated by the assignment, shying away from anything too personal or controversial, so I presented my narrative. I not only reconstructed painful moments of prejudice I faced due to my ethnicity and religion but also how these experiences often forced me into the role of a perpetrator or inspired me to become an agent of change. Three weeks later, I watched with pride as each day, one student presented his or her narrative with confidence and sincerity. We shared the pain a student experienced after being severely beaten for defending a friend against racial slurs; we understood another student’s frustration when others used the phrase, That’s so retarded; and we empathized with a student’s disorientation as an immigrant arriving in a hostile country. At the end of each reading, there was always silence, but this time it conveyed the students’ respect and understanding.

Another project the students embraced is a video-poetry project inspired by Pablo Neruda’s poetry, which urges humankind to awaken, to observe and, most importantly, to feel the majesty of the past, the urgency of the present, and the hope for the future. The expression of his experience takes the form of a series of complex and meaningful metaphors that draw on the tangible world to understand and share the intangible world of the heart. I asked students to write a twelve-line poem consisting of tightly constructed, complex metaphors about someone or something in their lives that represents the ideals of dignity, beauty, passion, and justice. They were to present this poem in a video montage, including images, the text of the poem, the student’s voiceover, and a background musical selection. The subjects of the students’ projects included their parents, the Pope, an elderly grandparent, and martial arts. The following is a selection from a student’s poem:

Andy’s “Karate Do—The Way of the Empty Hand”

The many colored belts—white, yellow, green, blue, purple, brown, and black—are the concentric rings of a maturing tree, records of passing time, endurance, and life.

The first hot, salty, liquid beads of sweat dripping on the mat are soothing droplets of rain, spotting the road, making it slick and dangerous, yet allowing release of a vital fluid that cleanses the body and spirit.

As a culminating project, I prepared a mock UN Millennium Summit, asking students to draw from the literature and other resources to prepare a forty-minute presentation on a current issue challenging our global community. The purpose of the presentation was to draw from the traveler’s experiences to present the unique contributions different cultures have made to the issue, the challenges that need to be addressed, and the similarities/differences across cultures. Each presenter was required to read three UN documents—The Millennium Declaration; Kofi Annan’s Millennium Report; and The Universal Declaration of Human Rights—compile an informational booklet of articles and other resources, deliver an engaging presentation on the issue, and lead a round-table discussion. In a concluding statement, each student delivered a moving message to UN leaders on what must be done to preserve, improve, and change the current status of the issue in hopes of a more peaceful and unified future.

Reflection

However uncomfortable it may feel, I am obligated to present myself as a real, human voice and body that represents so many silenced voices and oppressed bodies, even if they are outside my realm of experience. I want to present literary texts with the intention of developing the students’ self-concept. To different degrees, all literature addresses universal questions: How should I live my life? What goals are worth pursuing? What characteristics or attributes do I possess that are worth emulating? What is the human condition? How can one improve it? Returning to Reese’s question, teaching world literature is important because it mirrors society and provides unique perspectives on prejudice, violence, poverty, friendship, tolerance, courage, respect, and responsibility. It also encourages an understanding of the motivations that influence people’s actions and their consequences. When students do earn their place as global citizens, they will not only possess a rich and diverse collection of literature but they will also exude compassion, resiliency, humility and, most importantly, concern. I hope that they will embrace uncomfortable situations and continue to find the questions that challenge the social structures that perpetuate oppression, hatred, and fear. In this way, world literature goes beyond merely mirroring society to becoming a reflection of students’ inner potential to deal with that society.

SubscribeWorks Cited

Allende, Isabel. Zorro. New York: Harper, 2005.

Andric, Ivo. The Bridge on the Drina. 1945. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 1977.

Apocalypse Now. Dir. Francis Ford Coppola. Paramount, 1979.

Bender-Slack, Delane. “Using Literature to Teach Global Education: A Humanist Approach.” English Journal 91.5 (2002): 70–75.

Chang, Jung. Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China. 1991. New York: Simon, 2003.

Children of Heaven. Dir. Majid Majidi. Miramax, 1999.

Coetzee, J. M. Waiting for the Barbarians. New York: Penguin, 1980.

Conrad, Joseph. Heart of Darkness. 1918. Cheswold: Prestwick, 2004.

Cup. Dir. Khyentse Norbu. NTSC, 1999.

Devdas. Dir. Sanjay Leela Bhansali. NTSC, 2001.

Esquivel, Laura. Like Water for Chocolate: A Novel in Monthly Installments, with Recipes, Romances, and Home Remedies. New York: Doubleday, 1989.

García Márquez, Gabriel. One Hundred Years of Solitude. 1967. New York: Harper, 2004.

Hosseini, Khaled. The Kite Runner. New York: Riverhead, 2003.

Hotel Rwanda. Dir. Terry George. MGM, 2004.

Il Postino. Dir. Michael Radford. Miramax, 1995.

Larson, Charles R., ed. Under African Skies: Modern African Stories. New York: Farrar, 1997.

Maria Full of Grace. Dir. Joshua Marston. HBO, 2002.

McIntosh, Peggy. “White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack.” Independent School (Winter 1990): 31–36.

Moolaadé. Dir. Ousmane Sembene. 2004.

Motorcycle Diaries. Dir. Walter Salles. Universal, 2004.

Neruda, Pablo. The Essential Neruda: Selected Poems. San Francisco: City Lights, 2004.

No Man’s Land. Dir. Danis Tanovic. MGM, 2001.

Okri, Ben. The Famished Road. 1991. New York: Anchor, 1993.

Reese, James D. “Learning for Understanding: The Role of World Literature.” English Journal 91.5 (2002): 63–69.

Roy, Arundhati. The God of Small Things. New York: Harper, 1997.

Solzhenitsyn, Aleksandr. One Day in the Life of Ivan Denisovich. 1962. New York: Farrar, 2005.

Thief. Dir. Pavel Chukhraj. Sony, 1998.

To Live. Dir. Yimou Zhang. MGM, 1993.

Tsotsi. Dir. Gavin Hood. Miramax, 2004.

Y Tu Mamá También. Dir. Alfonso Cuarón. MGM, 2000.

Zeppa, Jamie. Beyond the Sky and the Earth: A Journey into Bhutan. New York: Riverhead, 1999.