This post is by guest writer Lissette Lopez Szwydky-Davis and member Sean P. Connors.

Is it acceptable to teach a popular culture adaptation of a canonical text as a substitute for the original literary work? What, if anything, is lost when students view a film adaptation of Great Expectations as opposed to reading Dickens’s nineteenth-century novel? And is there ever a good reason for students who are capable of reading Romeo and Juliet to study a graphic novel adaptation of Shakespeare’s play instead? We assume we aren’t the only English teachers to have wrestled with these questions. And yet we hear these ideas described as problematic because some teachers assume that popular culture and canonical literature exist in an antagonistic relationship. When teachers create opportunities for students to experience and produce literary adaptations, they invite them to participate in a practice that is arguably as old as the institution of literature itself.

We tend to understand adaptations—whether films, graphic novels, video games, or other forms—as a contemporary phenomenon, and think they somehow indicate a major change in literacy practices. In truth, however, the practice of adapting literature in multiple mediums dates back to antiquity. The ancient Greeks and Romans decorated pottery with imagery lifted from legends and epic poems such as those by Homer and Virgil. The reason the story of Odysseus or the fall of Troy are known today is because they have been adapted and remixed for centuries.

All of the modern forms of storytelling we teach are tied to the practice of adaptation. The rise of the novel as a literary form, for example, was in part sustained by adaptations for the popular stage and other media. Daniel Defoe’s bestselling adventure novel, Robinson Crusoe (1719), went through so many adaptations in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries that these popular versions were considered their own subgenre of entertainment: the Robinsonade (Green, 1990; Gould, 2011). The history of literary adaptation reveals clear connections not only between Defoe’s novel (itself a loose adaptation of the stranded sailor Alexander Selkirk’s experience) and centuries of adaptations in print, performance, and screen, but also among some of today’s popular reality TV shows, including Survivor and Naked and Afraid, all of which draw on the transhistorical popularity of the Robinsonade.

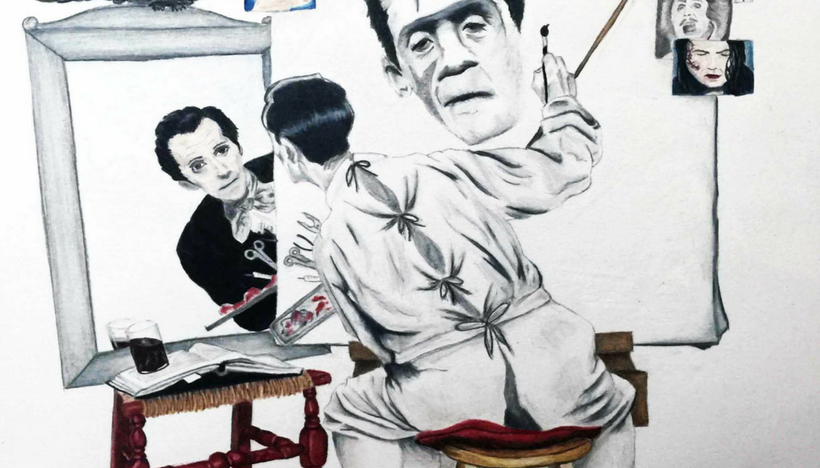

The early publication history of Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein gives us a better picture of how central adaptation, and popular culture, could be to the circulation of narratives. The novel was originally published anonymously in 1818 to a print run of 500. No additional copies were printed until five years later, after a major dramatization was announced. Shelley’s father, William Godwin, oversaw the publication of the second edition, released just in time to capitalize on the success of Richard Brinsley Peake’s Presumption; or, The Fate of Frankenstein (1823), a stage hit that went on to inspire several other adaptations in the 1820s. The second edition of Frankenstein revealed Shelley as its author and, with a print run of 1,500, quadrupled the total copies of the novel available in print. What’s more surprising for those unfamiliar with Frankenstein’s popular history, however, is that on any given night that Presumption was staged, more than 2,000 people could witness the story of Frankenstein and his Creature unfolding in a popular, visual medium. In other words, throughout the 1820s, more people came to Frankenstein via adaptations than through reading the novel, just as most people first encounter the story through adaptations today.

Students are often left with a double displacement when they read canonical literature. They don’t share the historical moment that produced the text they are reading, which requires teachers to sift through not only textual meaning but also related historical context. At the same time, most canonical authors weren’t writing texts with adolescent readers in mind (not to mention differences between nineteenth-century adolescents and the same age group today). Literature may hold an enshrined status in contemporary English classrooms, but many of the novels and plays we teach were created and circulated as forms of popular entertainment in their respective day. Curricula that ignore popular culture adaptations fail to acknowledge the value of introducing a well-known story (whether on its own or as a complement to a canonical text) in a medium better suited to introducing themes and piquing the interests of younger readers. We believe that teaching adaptations and helping students to create new versions of older stories provides a productive platform for better understanding the value of now-classic texts and their cultural relevance, both in the past and in the present.

Our appreciation for the merits of literary adaptation media has inspired us to offer a summer institute for K–12 teachers interested in learning more about how to engage students in studying popular adaptations as a way to deepen their understanding of canonical literary texts. For more information on this institute, funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, please visit https://monstersandheroines.uark.edu/.

Lissette Lopez Szwydky-Davis is assistant professor of English at the University of Arkansas, where she teaches and publishes in the areas of nineteenth-century British literature and culture, adaptation studies, cultural studies, and gender studies, as well as professionalization for arts and humanities students. You can follow her on Twitter at @LissetteSz.

Lissette Lopez Szwydky-Davis is assistant professor of English at the University of Arkansas, where she teaches and publishes in the areas of nineteenth-century British literature and culture, adaptation studies, cultural studies, and gender studies, as well as professionalization for arts and humanities students. You can follow her on Twitter at @LissetteSz.

Sean P. Connors is associate professor of English education at the University of Arkansas, where he works with preservice English teachers and writes about young adult literature, graphic novels, and new literacies. You can follow him on Twitter at @profconnors.

Sean P. Connors is associate professor of English education at the University of Arkansas, where he works with preservice English teachers and writes about young adult literature, graphic novels, and new literacies. You can follow him on Twitter at @profconnors.

Note: The drawing in the Featured Image is Art by Skye Ferrell.