This post was written by NCTE member Susan Gustafson.

“Can we do this again sometime?”

“Yeah, it was so fun!”

“Pleeeeeease.”

These were the pleas from my sixth-grade students after completing our first breakout game.

Breakout games have become popular activities in classrooms of all ages and disciplines. While they may seem to be designed for other content areas, they can be successfully used in ELA classrooms too.

What Is a Breakout Game?

Similar to escape rooms, breakout games require groups to work together to solve a series of challenges in order to open a locked container before the time limit expires. They are an engaging activity to review content as well as foster collaboration and problem-solving skills.

How Can Breakout Games Be Used in the ELA Classroom?

Breakout games can be used to review literary elements, figurative language, parts of speech, vocabulary, class routines/syllabus, and more.

When Is a Good Time To Do Breakout Games?

Breakout games are great to use for reviewing material, reinforcing concepts, building community, and anytime you want to help your students shake off the doldrums. At the beginning of the school year, they can be used to review previously learned material or as an engaging way to review the syllabus. They are perfect to get students up and moving after being sedentary. Also, when students tend to be more energized on days before breaks from school, we can embrace the energy with breakout games.

What Is the Set-Up for Breakout Games? Breakout games can be as simple or as complicated as the creator decides. There are many ways to set up a breakout game. Consider whether to have a physical game, a digital game, or a combination of the two. Also, consider the movement of the students. Will they be mainly in one area of the classroom or moving about to find clues?

A couple options for breakout game set-ups are:

- One box with multiple locks on the box. For each challenge, students figure out the combination to remove one of the locks. The game ends when the final lock is removed and the box is opened to reveal prizes or words of congratulations for completing the game. Clues may be hidden around the room or given to students after removing a lock.

- Multiple boxes or envelopes that each contain a clue. The first clue leads to a particular box or envelope which holds the second clue and so on, until students reach the final box or envelope. Locks may or may not be used. Clues may be hidden around the room.

What Materials Do I Need?

Besides the clues that you create, common physical materials include envelopes, a variety of locks (3-digit, 4-digit, directional, letter), and boxes for the clues. Some more advanced breakout games use invisible ink, black lights, or different types of puzzles.

Planning My First Breakout Game

In planning my first breakout game for my sixth-grade ELA classes, I analyzed my students’ learning needs to determine the focuses for the breakout game. The challenges focused on characterization, types of conflict, plot, and themes in Ray Bradbury’s “All Summer in a Day.” Once I knew the focuses of our learning, I determined to keep the set up of the game simple.

To introduce the activity, I created a forty-five-second video through a web-based video editing platform in order to dramatize the premise of our breakout game. In the story “All Summer in a Day,” set on Venus, Margot is locked in a closet by her classmates and misses the opportunity to see the sun, which only appears every seven years.

For our game, students were tasked to use their knowledge of characterization, conflict, plot, and theme in order to break Margot out of the closet in time to see the sun. The music and images in the video helped to build anticipation for the game when it was projected for the class alongside my oral introduction. Students then read the story, focusing on annotating characterization, types of conflict, plot, and themes.

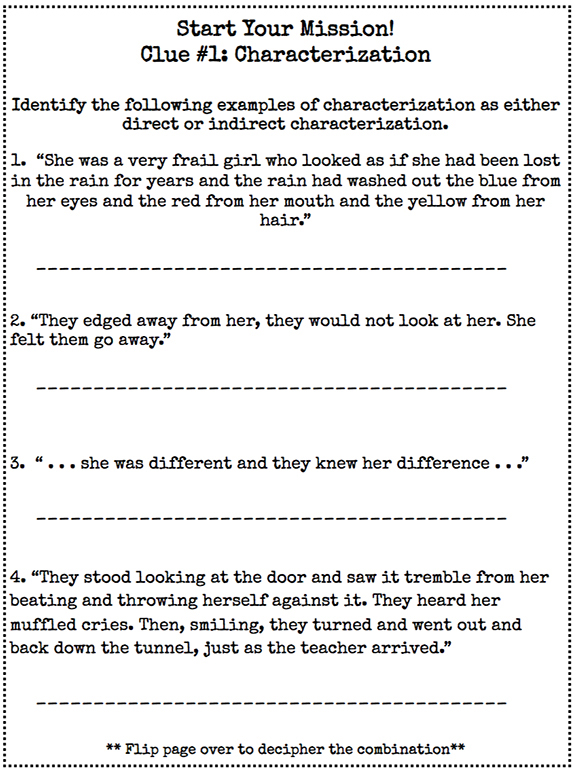

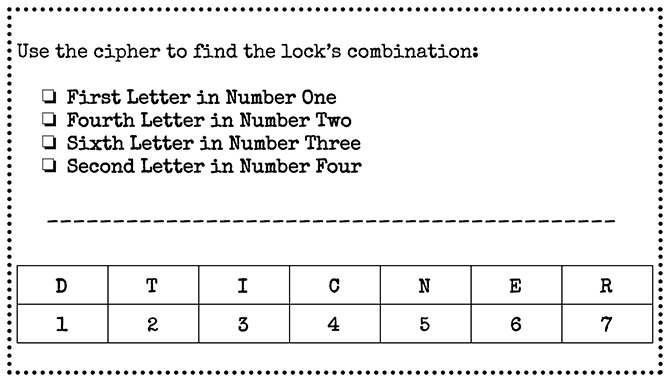

For the game, each group received the first clue on paper and four locked envelopes each containing the other clues. The first clue asked students to identify quotations from the story as examples of either direct or indirect characterization. Students wrote their answers about characterization on the clue and then used the cipher on the clue to get the combination to the second clue’s locked envelope.

If the combination did not work on the locked envelope, students worked together to correct mistakes. Once students correctly entered in the combination to the second clue’s lock, they opened the envelope for the second clue, focusing on identifying internal and external conflict in the story.

Students used their answers about conflict and the cipher to get the combination for the locked envelope holding the third clue. The process was repeated, with the third clue focusing on themes in the story and the fourth clue focusing on plot.

All of the clues used the same visual format of identifying quotations and using the same type of cipher for the lock combinations. The final envelope contained prizes for the students. Like at the end of many escape rooms, a photo area with props and signs was set up for the groups to snap their picture after completing the game.

Feedback from Students

After completing the breakout game, students individually completed a reflection form. The questions focused on groups’ cooperative learning, students’ individual learning, and feedback on the breakout game.

How did you engage in the game to help your group accomplish the task?

How did the group collaborate to solve challenges?

What did the group learn from any missteps?

If your same group were to do another breakout game, how might the group communicate or problem solve differently?

How did the breakout game add to your learning about characterization, conflict, plot, and theme?

How could the breakout game be improved?

Are you interested in doing more breakout games? Please explain your answer.

When asked what they would change about the activity, students’ most common answer was to add more challenges. All students responded that they would be interested in doing more breakout games. Student responses included the following:

“They are fun and they are also really helpful to people who want to get more help with the things we are learning.”

“It can help you be more social and cooperative with other people.”

“It is a fun way to figure out what parts of the text are what.”

Next Step

After the success of the first breakout game, one of the classes worked in groups to create their own breakout games. Students used the first game as a model but used different texts. The conversations that student creators had in constructing the breakout games showed a deeper level of engagement with the texts. What started out as students being participants in an enjoyable review activity became students taking ownership of their individual and collective learning.

Breakout games are engaging activities for students to demonstrate and deepen their learning in a variety of ELA areas. They can be a tool to strengthen communication and collaboration skills, while they enliven the classroom community.

Susan Gustafson is a middle school reading and language arts teacher in the Chicago area. She is also certified as a reading specialist and is pursuing a master’s degree in educational leadership. You can follow her on Twitter at @MiddleMsGus.