This post was written by NCTE member Sarah Elizabeth Smith Carter.

Educators are constantly reconsidering best approaches for diversity, equity, and inclusion in the classroom. At this point in the new year, I feel it’s a perfect time to remind readers of the endless ways that integrating primary research methods in our classrooms can support these efforts at all levels of education.

Primary research methods, also referred to as empirical research methods, ask students to conduct their own research through interviews, archives, surveys, and ethnographic work. This research encourages student and community engagement and helps to enable student positionality on current topics and issues. Scholarship on the benefits of primary research methods in the classroom has proven that the work is empowering for students and that it provides a way for students to investigate personal, professional, and political memories that have the potential to create a more inclusive classroom and ultimately, society.

This work matters—and it helps bring about change by helping teacher/scholars and student researchers develop agency and identity.

Jaycie Vos and Yadira Guzman promote the importance of primary source literary in “Understanding My Home: The Potential for Affective Impact and Cultural Competence in Primary Source Literacy.” Their research study “encourages the serious consideration of the emotional impact of primary source materials, particularly those that reveal underrepresented historical narratives, and their power to connect students to complex, larger narratives that can inform their understanding of their place in the world and within broader cultural contexts.”

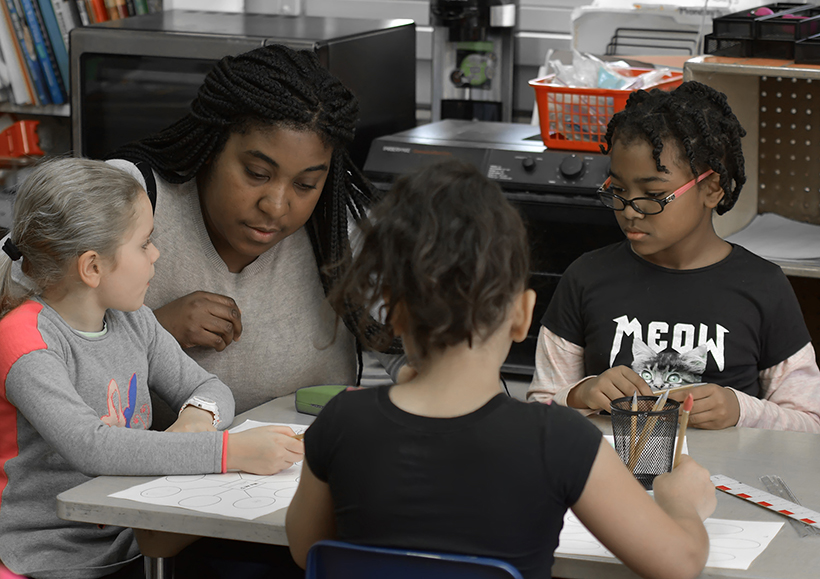

Assignments that include primary research methods can be included in any grade level starting in elementary school. For example, elementary school students could conduct interviews with family members and investigate their family history and heritage. Once complete, students could be asked to share their findings in a classroom setting, thus introducing a range of cultures and backgrounds within the shared space. Introducing such methods to students at a young age is one way to help them develop a wider perspective on others and on society.

Middle school students might take primary research methods beyond interviews with family members and extend those investigations with teachers at their school and beyond the school into the community. These students are also old enough to learn to search within the archives at their school and public libraries and learn to create simple surveys. Assignments that invite students to investigate on their own or within small groups help incite curiosity and discussion. This work affords young student researchers with an ability to look beyond their own immediate community and into a regional, national, and even global community.

Many opportunities exist for supporting high school and college students in integrating primary research methods into their coursework in ways that help them explore their stories and the stories of others. These students have the freedom and capability of working independently and/or in groups to utilize as many primary research methods as they are comfortable and/or knowledgeable using. A more challenging project in which students choose a topic or issue that they are interested in researching—and that teachers deem appropriate—can be a doorway to future projects and life possibilities.

Overall, the time spent teaching and discussing primary research methods within the classroom can be beneficial to all student populations. By encouraging an application of research that moves beyond browsing and reading articles in which the research has already been conducted, and by asking students to conduct the research themselves, students begin to appreciate the wide range of voices, cultures, and communities that make up our world.

Sarah E. S. Carter (ABD) is a lecturer at Clemson University, South Carolina.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.