This post was written by NCTE member Gabrielle Plastrik.

As a person who loves poetry and believes that there is a poem out there for each of us when we need it, I want students to find poems they enjoy. I also know that reading poems thoughtfully can help them expand their world views whether they enjoy them or not. Students become better academic readers through the study of poetry in part because short texts created with a lot of intention are opportunities to practice asking questions, re-reading, noticing patterns, and annotating in a manageable and reasonable way.

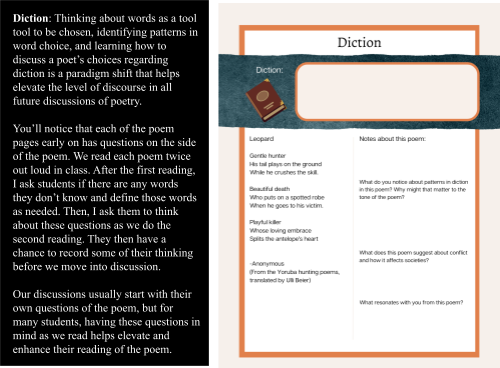

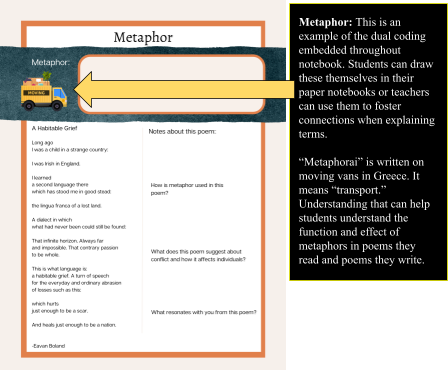

In my global humanities class, I work to include voices throughout time and across the globe. The “War Poets” cannot be limited to Sassoon, Brittain, and Owen. As long as there has been war, there have been poets writing about war. In selecting poems for the resource that I am sharing here, the major goals I had were to a) honor the cultures of the students in my classroom, b) share voices from places and times we had studied historically, and c) provide many lenses for thinking about war and conflict. In terms of skills, this poetry notebook is set up as an opportunity to learn the language of the discipline, practice employing a variety of specific poetic techniques, practice asking and answering questions about poetry, and make personal connections to poems.

I have students create their own poetry notebooks over the course of our conflict poetry unit. They take notes on paper and glue in poems and resources. I created this digital resource for those who need to type or who need additional scaffolding due to executive function concerns. Having the finished digital notebook also helps me support students who are absent for any given lesson.

Below are some lesson highlights from the poetry notebook:

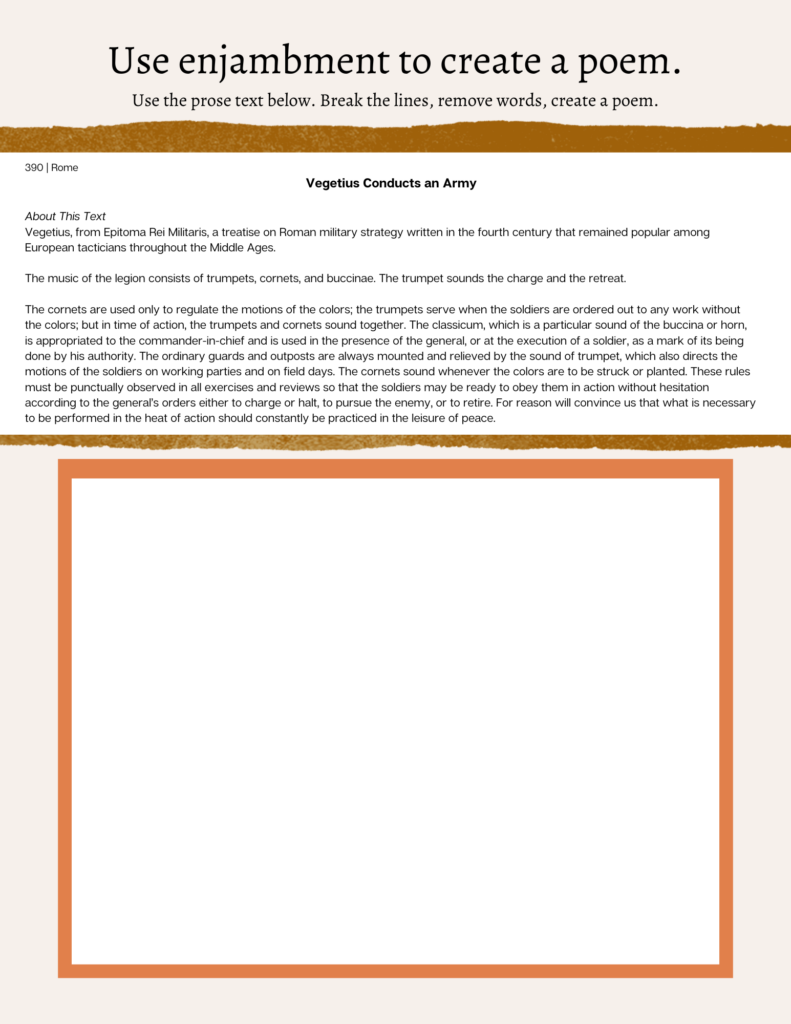

Enjambment: I found this lovely passage about the Roman Legion in Lapham’s Quarterly. Students work with a partner to choose words and phrases that seem significant to them. Then, without changing the order or the words and phrases, they construct a poem. I encourage them to remove insignificant connecting words for the first draft and to think about where they break the lines, sometimes even interrupting phrases they love, to help them see that line breaks are a tool that allows the poet to control which words carry weight for the reader.

This is a moment in their poetry writing when students unfamiliar with poetry writing realize the power of line breaks. They start to read poems with a greater awareness of the choices a poet could have made, which helps them think about the “why” of the choices the poet did make. Writing and reading skills go hand in hand here. Note: When I taught US literature, I did a similar activity with excerpts of Walden.

Imagery: In order to help students really understand the power of imagery, I use a lesson I adapted from the one Thylias Moss used in her Advanced Poetry Workshop at the University of Michigan.

I bring in a bag of sensory experiences and cue up various nature sounds on my computer. I ask students to write in prose about any real or imagined journey. After about four minutes of writing, I pause them and ask them to close their eyes and hold out their hands. I bring around two or three objects with different textures. After each student feels one object, I ask them to think about what the object they touched felt like, not what it was. This is generally really challenging for some of them. I give them the example of an orange. The texture of an orange is not what an orange is. Then, we practice describing the texture together. This modeling of tactile imagery helps the rest of the activity go well. Students then have to incorporate that description of texture into their journey writing. They write for a few minutes, and then we do the same sequence with sounds of water and birds. I bring around essential oils or foods to smell for olfactory imagery. For gustatory imagery, I choose something they can eat slowly and hold in their mouths. We end with visual imagery, and I either show them some of the objects they experienced or give them each postcards of landscape paintings. They write for a few minutes between each new sensory experience.

Because we have done the enjambment lesson already, I then ask students to read their writing, choose the words, phrases, lines, story elements, etc. that they would keep if they made this a poem, and they transform their journey writing into poems. This is usually a moment in the unit that elevates the writing of those who haven’t already been writing a lot of poetry. They start to see what is possible and how they can use details in unexpected or original ways.

Gabrielle Plastrik, NBCT, teaches at Charles Wright Academy in Tacoma, Washington. Over the last eighteen years, she has taught in independent and public schools in Illinois, Wisconsin, Maryland, and Washington. Plastrik graduated from the selective poetry creative writing subconcentration at the University of Michigan and has an MSEd degree from Northwestern University. She is passionate about mindfulness in education, interpretive discussion, and the ways brains learn.

Gabrielle Plastrik, NBCT, teaches at Charles Wright Academy in Tacoma, Washington. Over the last eighteen years, she has taught in independent and public schools in Illinois, Wisconsin, Maryland, and Washington. Plastrik graduated from the selective poetry creative writing subconcentration at the University of Michigan and has an MSEd degree from Northwestern University. She is passionate about mindfulness in education, interpretive discussion, and the ways brains learn.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.