The fact that Elizabeth’s teacher was able to translate the lesson from an in- person setting to fully online is impressive. Like so many teachers, she adapted to a new medium for teaching and learning and had to develop her skills in using technology to do so. She was able to navigate a number of tasks: screen- sharing a video, distributing materials via Google Classroom, and encouraging students to participate in a call-and-response format. She and the students were able to troubleshoot tech hiccups, and ultimately, they made it through the planned content.

Given this context, one could argue that this was a reasonably successful lesson in the height of pandemic pedagogy and emergency remote instruction. Yet, much as Dickens’s spirits invite Scrooge to see different visions of what was, what is, and what could be, we want to rethink and reimagine, focusing instead on what could have been done in that lesson to foreground and intentionally integrate digital literacy. We acknowledge the difficult circumstances that remote instruction presented to millions of teachers and students. Still, as teacher educators and longtime advocates of purposeful uses of technology, we hope that we can inspire our colleagues to move beyond translating comfortable pedagogies into online spaces and, instead, focus on developing authentic digital literacy practices.

THE NEED FOR DIGITAL LITERACY THEN

Nearly ten years ago, hearkening to a time now nearly twenty years in the past, we collaborated on an English Journal article that opened like this:

Nearly a decade ago, Troy coauthored with Jeff Grabill an article for English Education titled “Multiliteracies Meet Methods: The Case for Digital Writing in English Education.” In it, they argued that “writing teachers must commit to this digital rhetorical perspective on writing, or they will miss the opportunity to help their students engage effectively in the ICT [Information and Communication Technology] revolution taking place right now.” (58)

The purpose of our article then was to question just how far the field had come in the decade after Troy and Jeff made the assertion that digital writing must become part of the English language arts (ELA) curriculum. In 2013, we argued that it wasn’t simply a matter of translating what had always been done in traditional ELA classrooms to something digitally infused; rather, we suggested that English teachers were at a crossroads, with an opportunity to reconceptualize teaching and learning. We asserted that digital literacy needed to be centered in English classrooms and that, quite simply, this shift could not wait.

Now, nearly twenty years from Jeff and Troy’s first call— as we reflect on the impact of the pandemic and remote instruction— we find ourselves asking a familiar question: In what ways are English teachers intentionally integrating digital literacies into instruction? Certainly, COVID- 19 revealed systemic inequities in our education system— those of race, class, and gender identity among them— not to mention the need for equity in access to digital devices and broadband. We recognize that teachers, alone, cannot solve these challenges. Yet, the pandemic- induced shift to remote instruction also revealed that many teachers (though certainly not all) still rely on methods that do not put digital literacy at the heart of teaching and learning.

What do we mean by this? To answer this question, let’s look at Elizabeth’s student- eye view of the literacy practices that were most valued in the lesson described above: (1) “reading” was about having a book read aloud and then answering comprehension level questions about it; (2) “writing” included answering basic text- dependent questions posed by the teacher; and (3) “participating in discussion” meant waiting to be called on by the teacher and answering the question asked.

Even though Elizabeth used digital tools to connect to her teacher and classmates synchronously that day, she did not use them to critique what she read, to collaborate with her peers, or to develop her thinking about the text. Everything she did was part of what Anne Whitney would call the “schoolishness of school” and could have (and, indeed, has been) accomplished in a face- to- face setting without the use of digital technologies. In this sense, even as a tech infused opportunity for learning presented itself, many ELA classrooms reverted to traditional instructional practices. We wonder: What might this lesson have looked like if the teacher and students had taken advantage of the technologies available to them?

Before offering alternative visions of the lesson, we want to ground our ideas in the culmination of many decades of thinking, led by NCTE, related to the use of technology in the classroom. We take a quick look back at an NCTE policy statement released— either paradoxically or prophetically, depending on how we view it— in November 2019. By viewing this document through the hindsight of the pandemic school years that followed its publication, we see that its value has increased exponentially.

THE RENEWED IMPERATIVE FOR DIGITAL LITERACY NOW

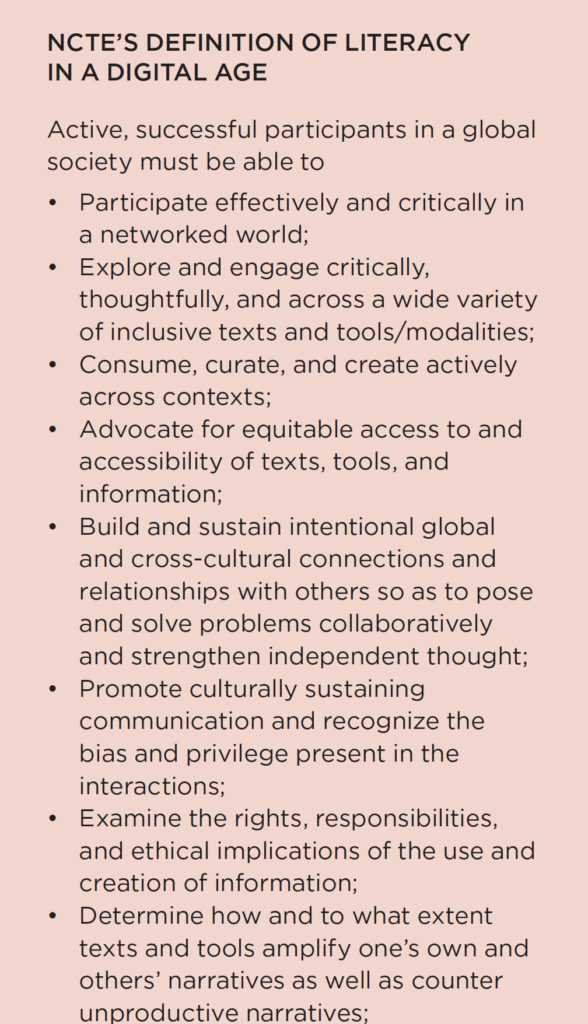

In 2019, NCTE adopted the “Definition of Literacy in a Digital Age,” a policy statement that describes “a collection of communicative and sociocultural practices shared among communities” that, in a digital age, “are interconnected, dynamic, and malleable.” The statement articulates nine tenets that outline the knowledge and skills needed to be literate in a digital society (see sidebar). The articulation of these skills followed three decades of research on the impact of newer technologies on literacy practices (or, as they are often called, literacies). Dozens of researchers have taken up the charge of examining topics broadly related to literacy and technology; indeed, there are too many to cite here, though we acknowledge a range of ideas from “critical digital literacies” (Ávila and Pandya) to “media literacies” (Hobbs) to “super- and sub- screenic literacies” (Lynch). In sum, researchers in the field of digital literacy have agreed on a key point that we feel often gets lost in conversations about technology in schools: simply having access to technology is not enough; digital literacy skills must be taught explicitly.

In 2019, NCTE adopted the “Definition of Literacy in a Digital Age,” a policy statement that describes “a collection of communicative and sociocultural practices shared among communities” that, in a digital age, “are interconnected, dynamic, and malleable.” The statement articulates nine tenets that outline the knowledge and skills needed to be literate in a digital society (see sidebar). The articulation of these skills followed three decades of research on the impact of newer technologies on literacy practices (or, as they are often called, literacies). Dozens of researchers have taken up the charge of examining topics broadly related to literacy and technology; indeed, there are too many to cite here, though we acknowledge a range of ideas from “critical digital literacies” (Ávila and Pandya) to “media literacies” (Hobbs) to “super- and sub- screenic literacies” (Lynch). In sum, researchers in the field of digital literacy have agreed on a key point that we feel often gets lost in conversations about technology in schools: simply having access to technology is not enough; digital literacy skills must be taught explicitly.

Even with more devices in the hands of more students than ever before, when we reflect on teaching during the pandemic, we are concerned that digital literacy still does not seem to be intentionally layered into ELA instruction. This argument laid the foundation for our 2013 English Journal article, where we (with a nod to Alfie Kohn) identified practices (e.g., counting slides) that could potentially “destroy” digital literacy. The argument is still relevant, nearly ten years later.

Teachers used a variety of tools during the pandemic: Google Classroom, Zoom, Padlet, Edpuzzle, Gimkit, Nearpod— the list is long. Often, however, the use of tools was in service of content delivery. Sometimes the content was presented by the teacher (for example, screen capturing a lecture and sharing it with students). At other times, content was presented by students (for example, posting responses to Flip). In both cases, the tool allowed for visual interaction as well as asynchronous learning and assessment. But we wonder: In what ways were digital literacies considered in the selection of the tool? How were students critically consuming or creating? How were they engaging purposefully in conversation with peers by using these tools?

To develop digital literacy, ELA teachers need to go beyond using digital tools to transmit content or encourage basic interactions. We need to develop methods and select technologies that allow students to consume, create, and collaborate in authentic ways. Given all that has changed in the past few years— and what has somehow not changed at all— what steps can we take to foreground digital literacy in our teaching?

As we reflect on the argument we made in the 2013 article, through the lens of the 2019 NCTE position statement and events leading up to the present moment, we want to be more positive in framing productive moves that we can make to support the development of digital literacy. Like Marley did for Scrooge, we hope to provide visions of what this instruction might look like. Before doing so, we offer four questions that teachers can ask as they plan lessons, modules, and units and select digital tools to meet their goals.

- How do I foster communication among students?

- How do I encourage accountable collaboration?

- How will students use digital tools to create, consume, critique, and think?

- How will students revisit, revise, and reflect on their thinking, learning, and growth?

These questions capture the ethos of what is articulated in NCTE’s position statement and provide a succinct way for English teachers to plan activities, assignments, and assessments that offer students opportunities to use digital tools in productive and authentic ways.

AN INTEGRATED APPROACH TO DIGITAL LITERACY

We now return to the scenario described at the beginning of this article and ask: Even though Elizabeth’s class was taught in a virtual setting using several technologies, were the students engaged in digital literacy practices? We believe that Elizabeth and her peers, like millions of other students in our nation and around the world, were not. We are mindful that teachers faced many challenges to ensure that their remote students were connected and engaged. However, we also observed that structural features that have held constant in “typical” ELA courses for decades— including an initiate- respond- evaluate talk pattern, superficial analysis of text through comprehension- level questions, and highly scripted written responses— were simply transferred into remote learning settings. In an era when students are increasingly disconnected from the intellectual work of substantive literary analysis, dialogic argument, and synthesizing their ideas, we contend— as we did nearly a decade ago— that digital literacy practices must become a part of daily instruction, whether face- to- face, fully online, or in a hybrid format. So, what might it have looked like if Elizabeth’s class had engaged in digital literacy practices?

In deference to Dickens, who provides three visions for Scrooge, we offer three alternative ways in which this synchronous, online, video- based session might have unfolded with an intentional effort to scaffold digital literacy practices and to respond to the four questions we have posed. (Of course, while Dickens is featured in this example, we hope teachers will use these techniques to augment instruction with a variety of texts— especially those that explicitly address important issues of diversity, equity, and inclusion.)

VISION 1: THE SPIRIT OF COLLABORATING AND QUESTIONING

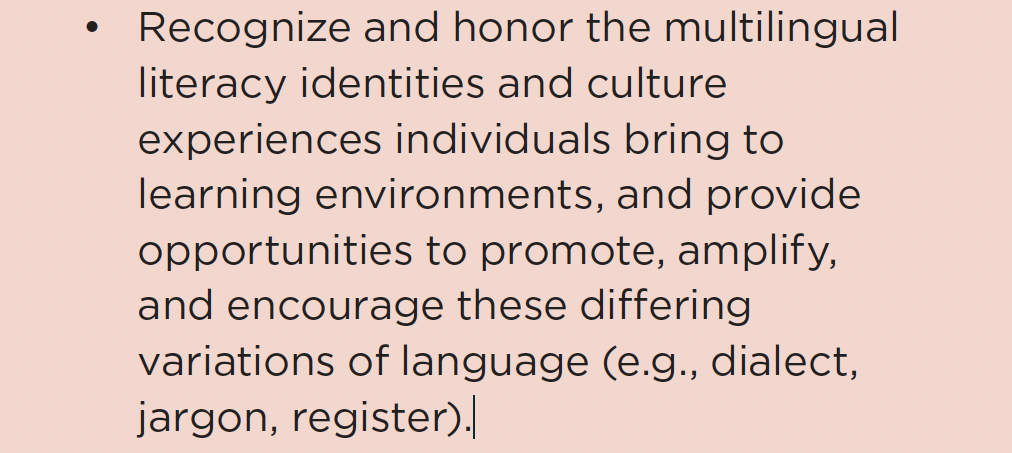

Elizabeth enters the online room and sees a note from her teacher to “choose two words that best describe Scrooge in the early stages of the story.” Once all students have logged in, the teacher shares a link to a Mentimeter presentation and asks each student to add their words. As the students hit submit, a word cloud forms and re-forms, and Elizabeth watches, noticing that one of her words appears larger than the other (see Figure 1).

After the teacher explains how word clouds are created— with the words being sized based on the number of times they have been entered into the poll— she moves students into breakout rooms to discuss (1) what they notice about the word cloud and (2) what they can say about the character of Scrooge based on the words the class has selected. After returning to the large group, a spokesperson for each breakout room shares a one- sentence claim that has been written by their small group. The teacher poses the inquiry question for the day: Can Scrooge change? Why or why not?

The teacher then directs the students, with a link in the chat, to the free and openly available version of A Christmas Carol on the Project Gutenberg website and asks them to follow along in the text as she plays an audio version from LibriVox. As Elizabeth reads and listens, she copies and pastes key words, phrases, and sentences from the text into a shared Google document so that her small group can discuss them after listening.

Back in the breakout room, Elizabeth talks with her peers about the notes they have added to the shared document. She volunteers to be a recorder and captures thoughts about the notes using the comment tool. Another student summarizes the team’s response to the day’s inquiry question, and finally, a reporter shares the thoughts with the large group. As a closing activity, the teacher releases a screenshot she has taken of the class’s word cloud and asks each individual to write an entry in their digital reading journal in response to the image and/or the day’s inquiry question, citing evidence from the small- group conversations or the large- group sharing session, before logging out of the online class. She uses this submission as the day’s formative assessment.

VISION 2: THE SPIRIT OF ANNOTATING AND DISCUSSING

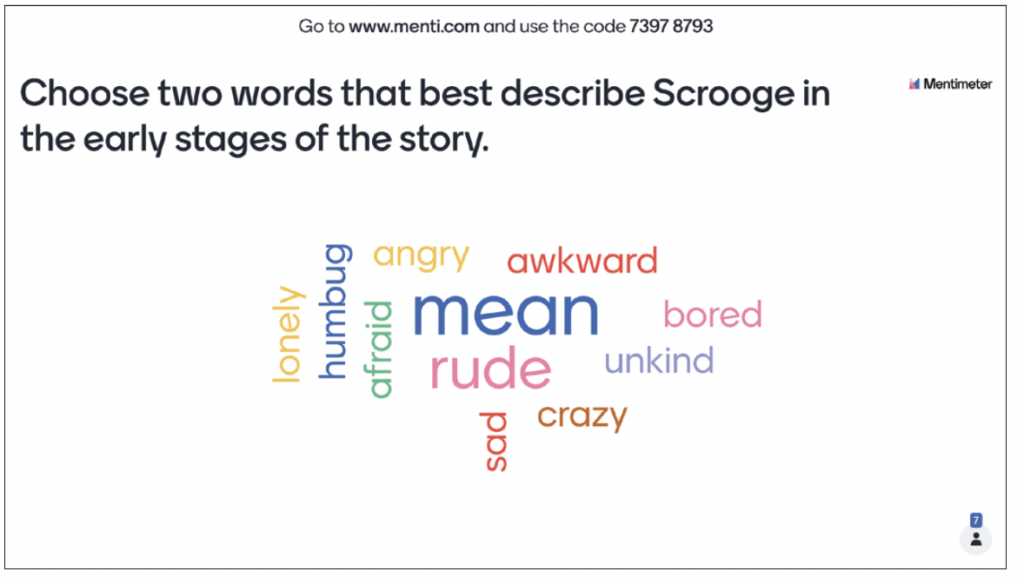

Elizabeth enters the online room and sees a note from her teacher to open a shared agenda and to click on the hyperlink with her group’s name. As the new tab opens, carrying her to a site called NowComment, the teacher tells the students that they will be reading aloud a few key paragraphs, as well as watching a film version of the same scene. In doing so, she reminds Elizabeth and her classmates to be looking at the ways that Dickens and the filmmaker are characterizing Scrooge.

FIGURE 1

This sample word cloud in Mentimeter illustrates a collection of words that describe Scrooge in the early stages of A Christmas Carol.

The teacher has taken the text from A Christmas Carol via Project Gutenberg and embedded it into NowComment, a free and openly available tool for digital annotation (see Figure 2), along with the scene between Scrooge and Fred from the 2009 Disney film with Jim Carrey in the starring role. Inviting students to use a simple protocol, she instructs them to listen to the read- aloud and offer “one comment on a thing you see, one on a thing you are thinking, and one on a question you are wondering about” as they follow along with the text. After the reading, she asks the students to read through what their classmates have written and to respond with a connection, question, or contradiction. They follow the same process for the video.

In a breakout room with two of her classmates, Elizabeth discusses the two texts (the written version and the film) and the annotations she has read, focused on the question, “Can Scrooge change? Why or why not?” To account for her thinking, she adds her own claim to the NowComment document.

FIGURE 2 This example NowComment page shows how the page might be set up for students to comment on the video clip and the text segment of A Christmas Carol (image blurred due to copyright restrictions).

VISION 3: THE SPIRIT OF CREATING WITH CONSTRAINTS

Elizabeth enters the online room and sees a note from her teacher to click on a link from the day’s interactive agenda. The tab opens a Google Drive folder with twelve items. There are six image files, each a social- media- style graphic with a key quote from the passage in A Christmas Carol. Also, there are six more screenshots from two different versions of the film, some of characters and some of settings. As students review the items in the folder, the teacher offers the following instructions:

You and a partner have thirty minutes to take the items in the folder— the quotes and the images from the films— and order them into a video in Adobe Express. You need to create a brief yet compelling argument, based on the quotes and the pictures from the films, about what is happening to the characters in the story at this moment and why this scene is so important. You can put the quotes and images in whatever order you want, but you need to use them all, and your video should be three to four minutes in length.

You will want to take five minutes to talk about the items in the folder and ten minutes to order them in your Adobe Express video timeline and sketch out the main ideas you want to discuss in your recording. Then, spend five minutes rehearsing and five minutes recording. Use your final few minutes to publish your video and make sure that you have a shareable link for other groups to watch.

Elizabeth moves into a breakout room with her partner and begins to work. The teacher sends periodic reminders through the chat function, encouraging students to stay on target with the timeline she has offered. About halfway through the session, Elizabeth and her partner are visited by the teacher to ensure that they are on track with their task. They move through the images and then the quotes, discussing the ways that they might organize their items and ideas about them. They are able to quickly rehearse and then record their video, wrapping up with just enough time to grab the shareable link before being pulled back into the main meeting room. Elizabeth shares her pair’s link on a document and sees that they have been assigned to offer responses to two other pairs of classmates, work that they will complete later as part of an asynchronous feedback process.

A RENEWAL OF THE CONVERSATION ABOUT DIGITAL LITERACY

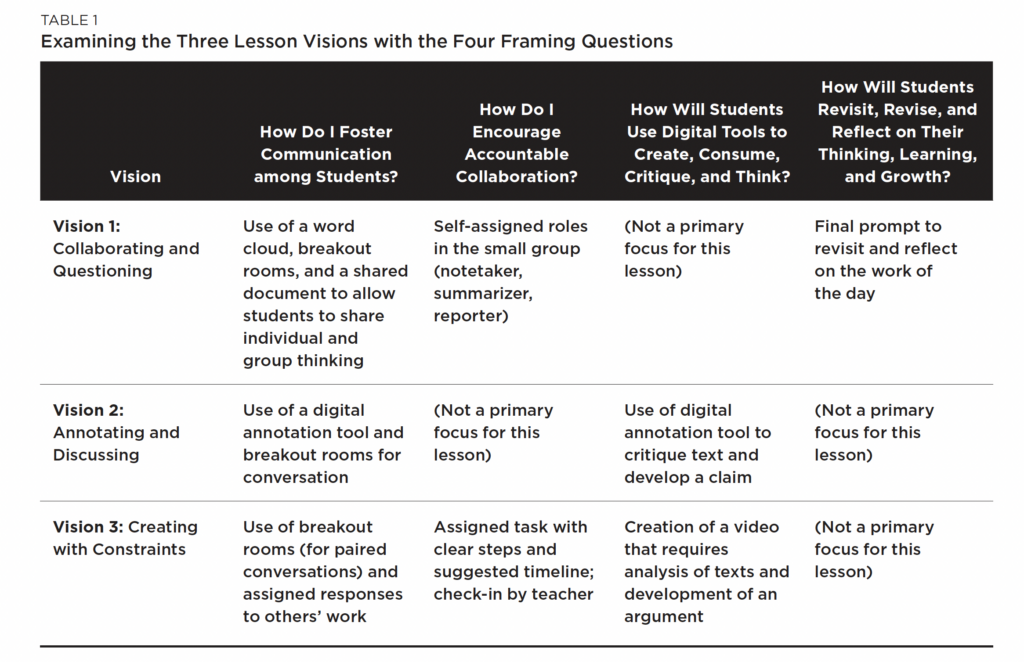

Earlier, we suggested that English teachers ask four succinct (though not simple) questions as they prepare lessons that integrate digital literacy through the intentional selection of digital tools. Table 1 summarizes our thinking for each of the visions. The three visions of lessons that put digital literacy practices at the heart of instruction are purposefully leveled and, as Table 1 shows, it is not necessary to incorporate activities that speak to all four of the fundamental questions in every lesson. For example, even though elements of cooperative learning are present in Vision 2, that lesson’s design does not center accountable collaboration as a focal digital literacy skill. Similar patterns emerge for Visions 1 and 3, where specific skills are emphasized. Rather than trying to address all four questions in every lesson, we suggest using them as a guide over the course of a week, or an entire unit, to weave digital skills together across multiple lessons.

Perhaps the most important lesson learned from pandemic teaching, however, is that simply having access to tools is not the answer for improving learning or literacy. We believe that teaching is the answer. Now that digital technologies such as the ones described in this article are more accessible and acceptable to teachers and students, it is time to put digital literacy at the center of ELA instruction.

In 2013, we suggested that to accomplish this goal, teachers needed to (1) put themselves out there, (2) be advocates, and (3) invite students to take (reasonable) risks. Here, we add a fourth idea: plan intentionally. By making the small moments in each lesson count and building in opportunities for genuine engagement, we can rethink the use of tech tools to help students be fully immersed in digital literacy practices. The responsibility for making these changes is not teachers’ alone. Administrative leaders must also rethink the policies and procedures that are preventing teachers from integrating digital literacies. Without being able to engage in sustained, immersive professional learning that identifies effective teaching practices and models of high- quality student work, teachers cannot be expected to make changes. Being generous with time for professional planning— including instructional and technology coaching— is a first step, as is making substantive changes to curriculum adoption, assessment practices, and teacher evaluation procedures.

The “spirits” we describe— collaborating and questioning, annotating and discussing, and creating within constraints— are indicative of the beliefs articulated in NCTE’s “Definition of Literacy in a Digital Age” and also represent the evolution of ideas that we have articulated in our work over the past two decades. We hope that, having seen a glimpse of teaching with digital literacy enmeshed in the pedagogy, others might, like Scrooge, see new opportunities not previously imagined.

WORKS CITED

Ávila, JuliAnna, and Jessica Zacher Pandya, editors. Critical Digital Literacies as Social Praxis: Intersections and Challenges. Peter Lang Publishing, 2012.

A Christmas Carol. Directed by Robert Zemeckis, Walt Disney, Pictures, 2009.

“Definition of Literacy in a Digital Age.” National Council of Teachers of English, 7 Nov. 2019, ncte.org/statement/nctesdefinition-literacy- digital- age/.

Dickens, Charles. A Christmas Carol. 1843. Project Gutenberg, 4 Mar. 2018, www.gutenberg.org/files/46/46- h/46- h.htm.

Grabill, Jeffrey T., and Troy Hicks. “Multiliteracies Meet Methods: The Case for Digital Writing in English Education.” English Education, vol. 37, no. 4, 2005, pp. 301– 11.

Hicks, Troy, and Kristen Hawley Turner. “No Longer a Luxury: Digital Literacy Can’t Wait.” English Journal, vol. 102, no. 6, July 2013, pp. 58– 65.

Hobbs, Renee. Mind Over Media: Propaganda Education for a Digital Age. W. W. Norton, 2020.

Lynch, Tom Liam. “Why Am I Saying to Forget the Screen When Talking about Screentime?” Tom Liam Lynch EdD, 3 Dec. 2018, tomliamlynch.com/2018/12/03/why- am- i- saying- toforget-the- screen- when- talking- about- screentime/.

Whitney, Anne Elrod. “In Search of the Authentic English Classroom: Facing the Schoolishness of School.” English Education, vol. 44, no. 1, 2011, pp. 51– 62.