This post is written by NCTE’s P12 Policy Analyst for Louisiana Jalissa Bates.

About 6.9 trillion gallons of rain pummeled Louisiana between August 8 and 14, according to CNN meteorologist Ryan Maue. About 60,000 homes have been damaged, 13 deaths announced, and thousands of citizens are now seeking recovery after unprecedented flooding.

I need this dialogue so much.

School is out for the rest of the week and I can’t help but wonder, “How are we going to start all over again?” First week of school procedures, expectations and schedules – do we repeat and do all over again? not only that, how are we to account for the mental states of faculty, staff, students, parents, and stakeholders at this devastating and traumatizing time?

The schoolhouse provides so much normalcy for our children and for us, the adults, too. Questions began to race across my mind as the rain continued to fall outside my home on Tuesday, August 16. So I ask my fellow educators in Louisiana: What was the scenario for you on Friday, August 12, as you learned school was being closed? Have you had any contact with administrators, fellow educators, parents, students, etc.? What has been the response? How can we as educators continue to provide stability to our community as we always have, although our own lives have been drastically affected? Does anyone else see the uncanny similarities to Hurricane Katrina? If children and teachers have to be displaced, how can we welcome them into our school climate?

I wrote this originally on my personal blog, The Young Scholar Society, on August 16 while nervously awaiting the reopening of school for Baton Rouge Charter Academy at MidCity. A sophomore from Tara High School, a professor from the University of Las Vegas, and a sympathetic New Orleans native offered advice to a few of my “provocative questions.”

However, when Monday August 22 rolled around, I found myself standing near the gym and multipurpose room, nodding and searching for words for all the faces I encountered. Instead of “Good morning,” the choice greeting that day was, “How did you fare?” Students drifted in for breakfast, some wearing uniforms and others in gym shorts or jeans. Homeroom teachers called absent students to find out if they were displaced and and to offer assistance.

It wasn’t until I happened to walk into Edna Coats’s first-grade classroom that I saw a true depiction of what students thought about the historic flooding of Louisiana 2016.

Micah’s drawing seemed very “busy,” capturing the cell phones that all the people held in their hands during an apparent evacuation. The floodwaters were blue, littered with trash in the drains and filling an illustration of his family’s car.

Micah’s drawing seemed very “busy,” capturing the cell phones that all the people held in their hands during an apparent evacuation. The floodwaters were blue, littered with trash in the drains and filling an illustration of his family’s car.

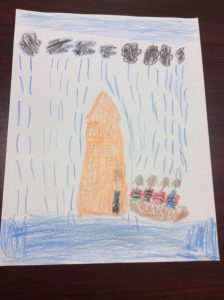

Tamia’s picture featured black clouds with rain coming down uniformly in sheets. The four passengers of a rescue boat were wearing red life jackets.

Tamia’s picture featured black clouds with rain coming down uniformly in sheets. The four passengers of a rescue boat were wearing red life jackets.

“I wanted to get the students to talk about what was going on,” Coats explained. “I knew the drawings would be therapeutic, a sense of healing.” Coats used a Coke bottle in the front of the class to demonstrate how the water came to spread out from its original place.

May the children and teachers of Louisiana impacted by the flood find peace in our schoolhouses.

Jalissa Bates is Louisiana’s Policy Analyst for K–12. Bates is also a recipient of the 2015 Early Educator of Color Leadership Award and contributed a chapter in Rowman and Littlefield’s Can I Teach That? Negotiating Race and Taboo Topics in the ELA Classroom.

Jalissa Bates is Louisiana’s Policy Analyst for K–12. Bates is also a recipient of the 2015 Early Educator of Color Leadership Award and contributed a chapter in Rowman and Littlefield’s Can I Teach That? Negotiating Race and Taboo Topics in the ELA Classroom.