This post is written by members Amy Miller and Meghan Jones.

“Writing can be my best friend.”

“Writing to me is the tool for creating a world that otherwise could not exist.”

“I want to be a writer who can write about things that are important not just in school. But world things.”

“Writing can bring life back to you when life is the worst it could possibly be.”

“Writing reminds me that the best is yet to come.”

After navigating our first year of heterogeneously grouped classes, the English 100H team, a group of teachers responsible for the ninth-grade classes, realized the need for a dramatic change for our first unit—we had to start the year off with a stronger push to rope all kids into what really matters in English class.

We wanted to cultivate in students the skills necessary to be successful learners and begin to instill in them the importance of being active, engaged readers and thoughtful writers. We worked backward with the idea of a summative assignment for which students reflected on who they are as writers, and we built a unit that provided students multiple opportunities to reflect on their own writing, engage with mentor texts, learn from their peers’ writing, and make choices about their learning along the way.

Here’s an overview of the two-to-three week process:

As a culture builder, a lesson in active listening, and a brainstorming activity, we began with peer interviews. Students asked each other questions about their memories of learning to write and the role of writing in their lives today. They recorded key words or phrases from their peers’ responses. Students then used the interview content to flash-draft responses to the question, Who I am as a writer?

Students explored mentor texts of published writers reflecting on why they write or read and identified strategies to then apply to their own writing. The idea of “reading like a writer” came from Rebekah O’Dell and Allison Marchetti of Moving Writers in their book Writing with Mentors. In a mini-lesson, we modeled the process of noticing and then naming strategies in our own words with a class model from short, accessible reflections by well-known authors. Students then explored other mentors in small groups, adding to our growing class list of strategies.

Students then personalized their learning by independently exploring an amassed list of mentors, including writers’ reflections, podcasts, TED Talks, and interviews with well-known writers and musicians. We continued to expand and refine our strategy list. After each successive round of exploring mentor texts, students returned to their own writing and tried a mentor strategy to revise what they had written. To ensure that students were meeting learning targets, we utilized exit passes as formative checks for understanding.

As the drafts took shape, teachers shared their own “Why I Write” drafts and had students locate strategies and offer feedback. Students then offered each other peer feedback on which strategies were working and which needed further attention.

Eventually, we turned to writing conferences during which students identified areas of revision and generated questions for the conference using a writer’s checklist. During the conferences, students took their own notes. Literacy specialists pushed into classes to help confer with students and ensure that each student received meaningful formative feedback.

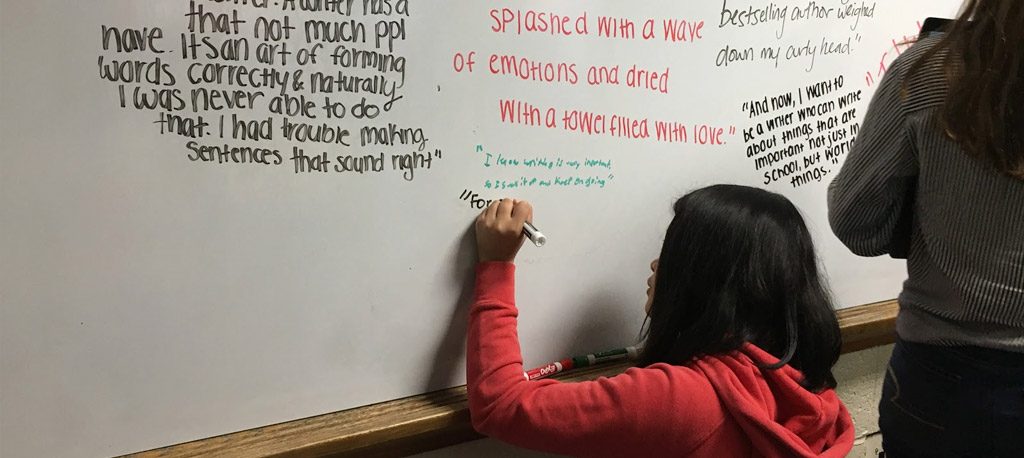

On the day their writing was due, we held a celebration of writing. NCTE’s #WhyIWrite site reminded us that collectively, telling why we write “gives voice to who you are and enables you to give voice to the things that matter to you.” So we decided to frame our celebration around “raising the volume”. In a gallery walk, students perused each other’s writing, located memorable lines, and quoted each other to build a collage of words on the whiteboard under #WhyIWrite. Placing the markers in students’ hands compelled them to appreciate each other’s words and to call out the student who uses writing to cope with reality, the friend whose journals capture everyday musings, and the peer whose written words create rich, imaginative worlds.

The written products were genuine in their self-reflection, rich with strategies gleaned from the mentor texts, authentic in voice and expression. We read stories of academic triumphs, sacred family reading times, private chronicles of the intimacies of their daily lives, and beaming elementary teachers who inspired our students to see themselves as writers for the very first time. Most importantly, students expressed that their love of writing dramatically waned as they advanced through the grades. Their pieces echoed a resounding desire to regain the love of writing that they once had as younger students. This not only validated our work but reinforces the enormity of the task we face as English teachers. It is our responsibility to teach all students at all levels that writing matters. Our students are writers with stories to tell—stories that deserve to be heard. Hopefully, we have brought them one step closer to gaining the tools and confidence needed to believe in themselves once again as writers who can change the world.

Amy Miller (Twitter @FHSEnglishCT) is the English department leader and Meghan Jones (Twitter @FHSliteracy) is a literacy specialist and instructional coach at Farmington High School in Farmington, CT.