Many parents, educators, educational administrators, and students themselves are talking about what is educationally safe for students in schools and on campuses—what they should or should not hear, see, or read.

Mark Yudof, president emeritus, University of California, and professor emeritus, UC Berkeley School of Law, notes,

Objectionable words and ideas, as defined by self-appointed guardians on university campuses, are often treated like violence from sticks and stones. Many students cringe at robust debate; maintaining their ideas of good and evil requires no less than the silencing of disagreeable speakers.

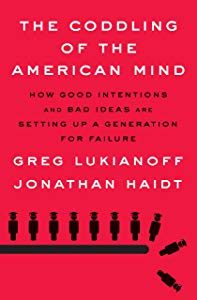

This new culture of “safetyism,” fear of hurting students with conflicting ideas, as described in a new book The Coddling of the American Mind by Greg Lukianoff, FIRE President and CEO, and Jonathan Haidt, Thomas Cooley Professor of Ethical Leadership at New York University’s Stern School of Business, is anything but safe.

This new culture of “safetyism,” fear of hurting students with conflicting ideas, as described in a new book The Coddling of the American Mind by Greg Lukianoff, FIRE President and CEO, and Jonathan Haidt, Thomas Cooley Professor of Ethical Leadership at New York University’s Stern School of Business, is anything but safe.

[The authors] show how the new problems on campus have their origins in three terrible ideas that have become increasingly woven into American childhood and education: What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker; always trust your feelings; and life is a battle between good people and evil people. These three Great Untruths contradict basic psychological principles about well-being and ancient wisdom from many cultures. Embracing these untruths—and the resulting culture of safetyism—interferes with young people’s social, emotional, and intellectual development. It makes it harder for them to become autonomous adults who are able to navigate the bumpy road of life.

Coaauthor Jonathan Haidt notes in an NPR interview,

A culture of “safetyism”—including safe spaces and trigger warnings—is setting up a generation for failure. . . . College is a special place [where] we should be emphasizing our common . . . humanity . . . and then we will be much better able to deal with issues of justice and exclusion.

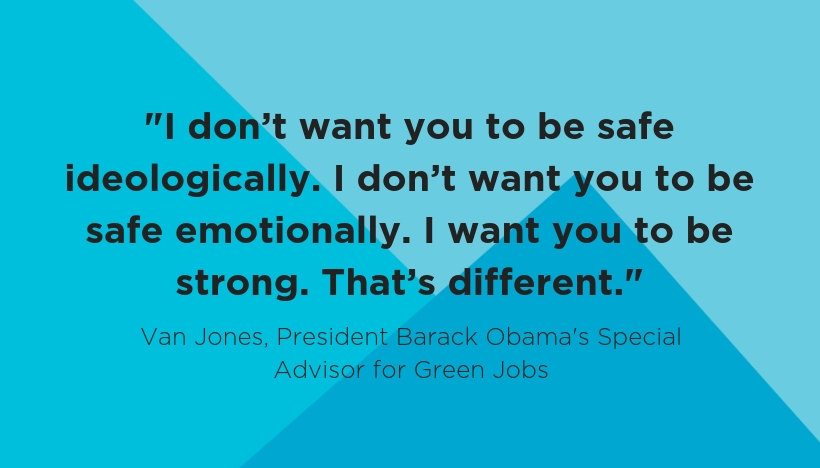

Van Jones, news commentator and former advisor to President Obama, echoes these findings in a talk at the University of Chicago:

He says the words quoted at the top of this blog and then goes on to speak to students,

I want you to be offended every single day on this campus. I want you be deeply aggrieved and offended and upset. And I want you to learn how to speak back. Because that’s what we need from you in these communities.

In his review of the book, Thomas Chatterton Williams of The New York Times Book Review warns of the damage the culture of “safetyism” can cause to our nation and democracy,

The consequences of a generation unable or disinclined to engage with ideas that make them uncomfortable are dire for society, and open the door—accessible from both the left and the right—to various forms of authoritarianism.

Michael Bloomberg, Founder of Bloomberg LP & Bloomberg Philanthropies and 108th Mayor of New York City, goes on to say in his review,

Rising intolerance for opposing viewpoints is a challenge not only on college campuses but also in our national political discourse. The future of our democracy requires us to understand what’s happening and why—so that we can find solutions and take action.

They’re right, of course, as the NCTE Position Statement on Academic Freedom emphasizes,

Inherent in academic freedom is both a moral and educational obligation to uphold the ethics of respect and protect the values of inquiry necessary for all teaching and learning.

“How can we as a nation do a better job of preparing young men and women of all backgrounds to be seekers of truth and sustainers of democracy?” asks Cornel West, professor, Harvard University, and author of Democracy Matters; and Robert P. George, professor, Princeton University, and author of Conscience and Its Enemies in their review of the new book.

Here are a few ideas.

If you’re on a college campus,

- Do make friends with the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE) and their resources.

- You may want to read The Atlantic article, “The Coddling of the American Mind,” that led to the book. Greg Lukianoff talks about the article in a 2016 interview:

- See if your university has adopted the University of Chicago Statement on Freedom of Expression or one just like it. The statement notes,

Our students . . . should have freedom to discuss any problem that presents itself. . . . The “cure” for ideas we oppose “lies through open discussion rather than through inhibition.” . . . “Education should not be intended to make people comfortable, it is meant to make them think. Universities should be expected to provide the conditions within which hard thought, and therefore strong disagreement, independent judgment, and the questioning of stubborn assumptions, can flourish in an environment of the greatest freedom. . . .

Although the University greatly values civility, and although all members of the University community share in the responsibility for maintaining a climate of mutual respect, concerns about civility and mutual respect can never be used as a justification for closing off discussion of ideas, however offensive or disagreeable those ideas may be to some members of our community. . . .

In a word, the University’s fundamental commitment is to the principle that debate or deliberation may not be suppressed because the ideas put forth are thought by some or even by most members of the University community to be offensive, unwise, immoral, or wrong-headed. It is for the individual members of the University community, not for the University as an institution, to make those judgments for themselves, and to act on those judgments not by seeking to suppress speech, but by openly and vigorously contesting the ideas that they oppose. Indeed, fostering the ability of members of the University community to engage in such debate and deliberation in an effective and responsible manner is an essential part of the University’s educational mission.

- If you’d like to work to get your campus to adopt the free speech principles of the University of Chicago statement, FIRE tells you how.

FIRE also offers resources for high school teachers and schools.

A Huffington Post article, “Safe Spaces On College Campuses Are Creating Intolerant Students,” quotes President Obama’s s 2015 speech to high school students in Des Moines, Iowa, which echoes the University of Chicago statement, The Coddling of the American Minds, and those quoted above:

Look, the purpose of college is not just, as I said before, to transmit skills. It’s also to widen your horizons; to make you a better citizen; to help you to evaluate information; to help you make your way through the world; to help you be more creative. The way to do that is to create a space where a lot of ideas are presented and collide, and people are having arguments, and people are testing each other’s theories, and over time, people learn from each other, because they’re getting out of their own narrow point of view and having a broader point of view.