This post was written by NCTE member Julie Wright as part of Build Your Stack,® a new initiative focused exclusively on helping teachers build their book knowledge and their classroom libraries. Build Your Stack® provides a forum for contributors to share books from their classroom experience; inclusion in a blog post does not imply endorsement or promotion of specific books by NCTE.

A decade ago, the American diet was six glasses of water a day, 3 servings of fruit and veggies, low carb, lean protein, and 34 gigabytes of written content each day—that is approximately 100,000 words that come across our eyes and ears during waking hours in a 24-hour period.

In 2009, researchers at the University of California-San Diego published a startling report that concluded that Americans had a “voracious appetite for information and entertainment.” Contrary to the hand-wringing concern that we were all reading less, the study suggested that we are actually reading more, but differently. On computers, tablets, and phones, we’re ingesting vast amounts of information.

Here we are in 2019, and as I work in schools across the country, I reflect on that study of digital grazing. One of the questions in my mind, is: when I read online, how often does it whet my appetite for the full text? Does that amazing article in The Atlantic drive me to put that author’s full-length book in the cart? Does that daily blog I look forward to reading lead to a longer commitment to that authors’ work? When I’m in a cup half-full mode, yes.

I began to test out my theory that “short” leads to “long” with readers in various school settings, and a pattern has emerged.

Whether it’s in a second-grade classroom or in an eleventh-grade Global Studies class, if I launch our work with a captivating short text, it almost always grabs students’ attention, and often leads to students taking up longer texts on the topic.

I believe this is true because short texts often pique students’ curiosity, creating the need or desire to read more. Here’s why:

- Short texts feel manageable. They give the reader a sense of I can read this from beginning to end. Fear of failure in finishing may sometimes be a cause of students’ failure to launch a longer text.

- By design, short texts give a small amount of information. If a reader is interested in the story, topic, or author, it’s natural to want to satisfy your curiosities. Short texts invite interested readers to read more.

- Since short texts are designed to get the ideas across quickly and succinctly, using every inch of real estate on the page to get the information or point across is critical. Short texts often have a visual element that makes readers want to ponder, reread, and investigate further. And the texts students read next are often longer in length.

Here are some short texts that build big engagement.

101 Books to Read Before You Grow Up, written by Bianca Schulze, includes 1- and 2-page spreads sharing book recommendations that kids should read before they grow up. The beautifully designed side panels are packed full of information and the center panel gives a kid-oriented book review, including a short summary. Readers of all ages enjoy the Did You Know? fact box and the relatable titles included in the What To Read Next? box.

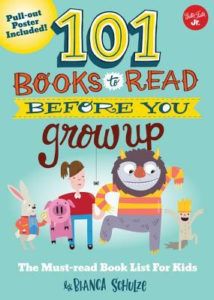

Separate Is Never Equal—Sylvia Mendez & Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation, by Duncan Tonatiuh, captures the Mendez family’s efforts in helping bring an end to segregated schooling in California in 1947. This picture book creates a context for learning about an important topic and a launching point, if desired, for deeper thinking, reading, and discussion about the 14th Amendment, segregation in the 1940’s and 1950’s, Mexican-Puerto Rican heritage, and the Mendez family’s contributions to history.

Separate Is Never Equal—Sylvia Mendez & Her Family’s Fight for Desegregation, by Duncan Tonatiuh, captures the Mendez family’s efforts in helping bring an end to segregated schooling in California in 1947. This picture book creates a context for learning about an important topic and a launching point, if desired, for deeper thinking, reading, and discussion about the 14th Amendment, segregation in the 1940’s and 1950’s, Mexican-Puerto Rican heritage, and the Mendez family’s contributions to history.

Toys! Amazing Stories Behind Some Great Inventions, by Don Wulffson, is packed with short texts that give readers new insights behind some of the greatest toys ever invented. When readers learn that Silly Putty was invented by mistake and that Play-Doh was originally sold as Magic Wallpaper Cleaner, it will leave them wanting to read further and know more.

Toys! Amazing Stories Behind Some Great Inventions, by Don Wulffson, is packed with short texts that give readers new insights behind some of the greatest toys ever invented. When readers learn that Silly Putty was invented by mistake and that Play-Doh was originally sold as Magic Wallpaper Cleaner, it will leave them wanting to read further and know more.

Out of Wonder: Poems Celebrating Poets, by Kwame Alexander, Chris Colderley and Marjory Wentworth, celebrates the unique styles and voices of poets. Each section of this book is filled with short poems that invite readers to think and connect to words in new ways. Additionally, readers can go a step further by reading bios about each poet being celebrated at the end of the book.

Out of Wonder: Poems Celebrating Poets, by Kwame Alexander, Chris Colderley and Marjory Wentworth, celebrates the unique styles and voices of poets. Each section of this book is filled with short poems that invite readers to think and connect to words in new ways. Additionally, readers can go a step further by reading bios about each poet being celebrated at the end of the book.

Eye to Eye: How Animals See the World, by Steve Jenkins, is a favorite to be read over and over again. Start at the beginning of this short text or jump into the page that seems most interesting—either approach will make readers think about what they already know about certain animals and how animals see the world around them. It’s hard not to want to read more when you learn that a panther chameleon can look in two directions at once, watching for prey so that it can eat dinner while also on the lookout for danger. This book leaves readers with wonderings about some amazing animals in the world and creates a reason for reading more!

Eye to Eye: How Animals See the World, by Steve Jenkins, is a favorite to be read over and over again. Start at the beginning of this short text or jump into the page that seems most interesting—either approach will make readers think about what they already know about certain animals and how animals see the world around them. It’s hard not to want to read more when you learn that a panther chameleon can look in two directions at once, watching for prey so that it can eat dinner while also on the lookout for danger. This book leaves readers with wonderings about some amazing animals in the world and creates a reason for reading more!

A Graphic History of Sport: An Illustrated Chronicle of the Greatest Wins, Misses, and Matchups from the Games We Love, by Andrew Janik, immediately captures your attention because of the basketball texture on the front cover. The simple graphics and short texts that span these two-page spreads keep the reader turning pages, and the book is packed with interesting and unusual facts about sports history.

A Graphic History of Sport: An Illustrated Chronicle of the Greatest Wins, Misses, and Matchups from the Games We Love, by Andrew Janik, immediately captures your attention because of the basketball texture on the front cover. The simple graphics and short texts that span these two-page spreads keep the reader turning pages, and the book is packed with interesting and unusual facts about sports history.

The short story Eleven is one of many great stories included in Woman Hollering Creek, by Sandra Cisneros. This is a perfect resource to use when pairing texts for students to read together. For example, Eleven pairs nicely with any of the short stories included in Johanna Hurwitz’s book Birthday Surprises: Ten Great Stories to Unwrap, in which students can explore short stories about birthdays.

Or pair Eleven with Tuesday of the Other June, by Norma Fox Mazer, in which students can explore standing up and using their voices. Reading several short stories with a common thread gives students multiple opportunities to make connections across texts and read for deeper meaning.

References

Bits. (2009, December 9). The American Diet: 34 Gigabytes a Day [Blog Post]. Retrieved from https://bits.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/12/09/the-american-diet-34-gigabytes-a-day/

Julie Wright is an educational consultant and instructional coach. She is the coauthor of What Are You Grouping For?, Grades 3-8: How to Guide Small Groups Based on Readers—Not the Book (Corwin, 2019.) She is currently working on a new book focused on the power of using short texts, to be released later this year by Benchmark Education. Reach Julie at www.juliewrightconsulting.com or on Twitter @juliewright4444