This post was written by NCTE member Vikki Orepitan.

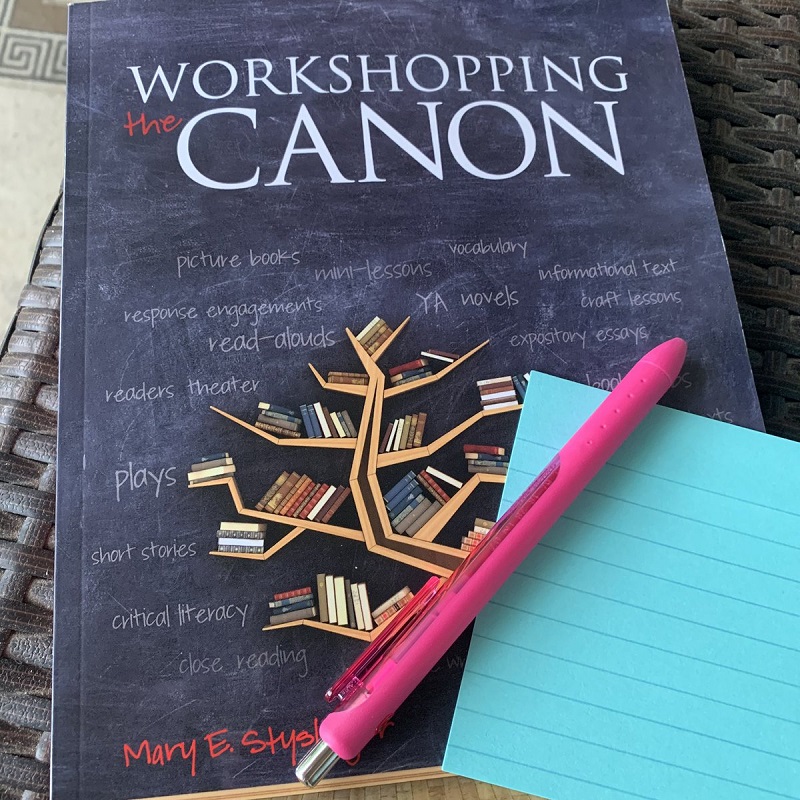

For the second week of NCTE Reads, we focused on good practices. In chapter 2 of Workshopping the Canon, author Mary Styslinger explains how to use reading aloud as a workshop tool.

Here, Styslinger peeked inside my brain, and addressed me directly: “I think many of us who work in middle and high schools do not embrace workshop structures like read-alouds because we cannot envision what they might look like in our own classroom. . . . We have to prepare ourselves and our students—the magic doesn’t occur without practice.”

I do read to my students: the syllabus on the first day of class (“Now you can’t say you didn’t know the policy!”), that one test question that got cut off on every copy (“The copier tried to foil your test, but I SAVED you! You’re welcome!”). If I’m feeling adventurous, I’ll read my favorite poem, or a passage I really love in one of our anchor texts. If I’m feeling desperate, I read the part of the novel that everyone has questions about or absolutely-pretended-to-read-while-watching-Ugly-Betty-or-whatever-it-is-the-kids-watch-these-days.

This week, however, Styslinger inspired me to read picture books out loud. Out. Loud!

I practiced reading to my son, my dog, and my mom, whether they wanted me to or not, and Styslinger is right! “Middle and high school teachers especially need to practice reading picture books.”

We definitely need to practice! It’s hard to read and show pictures, and it’s incredibly hard to read with voices and animation if you haven’t before! Luckily, my seven-month-old and my blue heeler only want to devour books in a literal sense at this point, and the-law-of-moms says she has to clap after I perform literally anything, but, Phew! It was tough! (As a side note, may I recommend Even Superheroes Have Bad Days by Shelly Becker and Jabari Jumps by Gaia Cornwall—I can’t wait for my son to be old enough to enjoy them with me!)

In our TALK thread this week, Lisa Storm Fink, NCTE Professional Learning and Member Engagement Project Manager, asked us to provide examples of texts we might use for aesthetic and for efferent purposes.

I appreciate the conversation, especially the reiteration that all texts ask you to both read for whole meaning/connection to the text and to read for bits of information. A shout-out to Sue (Thank you, Sue!) for reminding us that “as readers we shuttle back and forth between the stances but may lean in one direction more than the other depending on the text and the ‘reservoirs of experience we bring to the transaction’.”

In the MAKE activity, we wrote our own questions to prompt personal responses from our students.

This was a learning experience for me because I have limited experience with reader response as a formal classroom tool. I think my reader’s response questions might have rung a little formal (think Socratic seminar), but after rewatching the videos of Styslinger and the three contributing teachers, I think I understand the concept a bit better.

Really, the reader response format is meant to create engagement. In the video, Styslinger explains that reader response is not analysis and isn’t meant to replace it. I found this immensely reassuring—one of my personal misconceptions about reader’s workshop is that it’s “low level.” Listening to Styslinger clarifies that analysis isn’t going away—rather than beginning with the historical or authorial relevance of a text, we’re going to begin with a student-to-text connection. I’m all for it!

TAKE was especially useful to me this week—I actually created a special folder so that I don’t lose all the resources before I get a chance to flesh out my own units.

This week, I most appreciated the videos of conversations between Styslinger and the teachers who opened up their classrooms to her—in a recorded web seminar, they discuss how each of them uses the workshop model in their classroom to meet the unique needs of their students and their teaching environment. They provide ample resources and explanations, and the information is incredibly helpful! I took notes (Raise your hand if you’re still a nerd—Okay, good, it’s not just me!) and wrote down questions to bring back to my copy of the book.

In the text itself, I found that Styslinger and I are singing the same tune! In chapter 4, she addresses critical literacy, which is essentially my entire classroom model! Using the reader response as a jumping off point, Styslinger asks students “to search for the author’s underlying messages and assumptions.” She asserts that analytical readers need “to understand the text’s purpose in order to avoid being manipulated by it. They question who is writing the text and contemplate who is deciding what is included and excluded within its pages.”

I think sometimes because a work is part of “the canon,” we’re afraid to question or criticize it—Styslinger encourages her students to question the goals and biases of a work in order to better understand the cultural influences within the work itself and with us as readers.

I think a big assumption—that perhaps no one addresses because it should be obvious—is the incredible amount of planning and preparation that needs to go into a classroom in this structure. So if you’re like me, you’re going to need to find your inner Erin Condren or Marie Kondo, and organize yourself! Buy a planner, use a calendar, lean hard on your incredibly organized and supportive teaching partner, but be sure to make time to work through what your units will look like, and how you’ll select supplemental texts, and when you’ll curate your amazing list of independent reading choices.

If you’re that person waiting on the copier to warm up 20 minutes before 1st period—just know that we love and support you-—but you’re going to have to Step. It. Up. Don’t worry! I’m right behind you!

Featured image from @DavisTeachELA on Twitter as part of #NCTEReads.

Vikki Orepitan is a 9th grade Pre-AP English teacher at Cinco Ranch High School in Katy, TX. This year she was awarded the Mercedes Bonner Leadership Award by TCTELA (Texas Chapter of NCTE) as well as the NCTE Intellectual Freedom Award for publicly opposing her district’s ban of Angie Thomas’s novel, The Hate U Give. She has taught multiple levels of English as well as Ethics (Civics) to students in Abu Dhabi and in Texas in grades ranging from 7 to 12. Inspired by her childhood teachers, her college instructors, and her mentors, she wishes to empower educators (and students) to challenge injustice and model leadership in their communities.