From the NCTE Standing Committee on Global Citizenship

This post was written by NCTE member Kylowna Moton.

“Far from demonstrating idleness or a lack of commitment to your chosen field, time away leads to insights you won’t gain in your normal habitat and can inspire a sense of greater purpose in your work.” —David W. Wildermuth

Welcome to summer, educators. You deserve a break. Yet the truth is that many of us have already started to prepare for next year’s students. I tend to start this process well before my spring students have even started their final exams. I write myself notes reflecting on what went well, and even more about what could stand to be improved. When the summer actually starts, the time away from the classroom gives me a chance to start working out the details of the upcoming semester while the student experiences, and the ideas they generated, are still fresh in my mind.

What I am thinking about most this summer is improving the way I communicate to my students the higher purpose—the practical application—of what I am teaching and what they are asked to learn.

In the midst of assessments, standards, student learning outcomes, policy changes, committee objectives, and other pressures from beyond the classroom, it’s too easy to lose our sense of the end goal of our work with students, as we are swept up in the myriad details of our daily practice. However, it is this understanding that students may need the most.

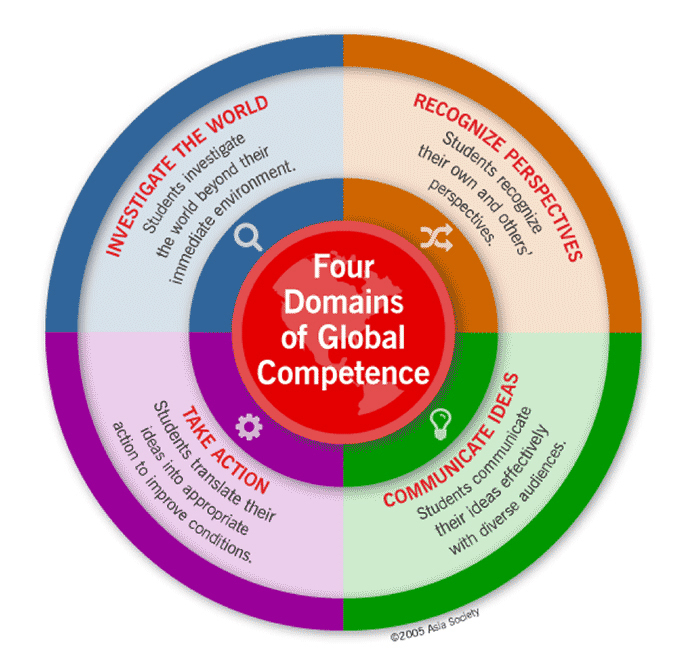

One resource that can help to establish a clear framework for teaching is the work done with domains of global competencies.

Source: California Global Education Project

I first encountered the global competencies in a session with California International Studies Project (now the California Global Education Project) at a California Association of Teachers of English (CATE) annual convention, and I immediately saw in the global competencies the potential to frame and focus the work I do in my English composition classes.

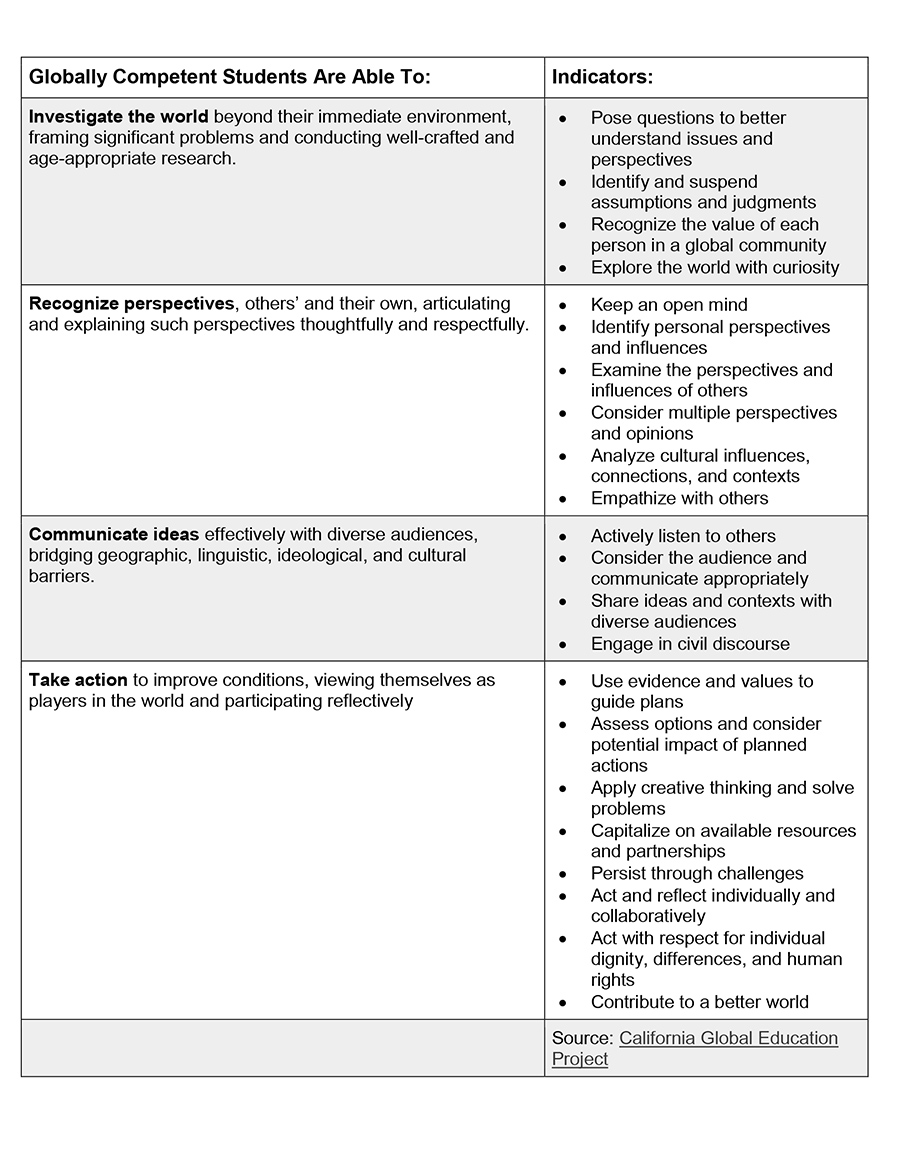

The first three of the four competencies (investigating the world, recognizing perspectives, and communicating effectively) are the macro-skills at the heart of not just an English composition class, but any class in the humanities or liberal arts. The indicators, sometimes referred to as “soft skills,” are what students need to be able to do in order to accomplish the macro-skills.

A cursory glance at the list of indicators reveals that the skills emphasized (suspending judgment, analyzing influences, considering multiple perspectives, empathizing with others, active listening, engaging in civil discourse, etc.) are what reasonable people expect to see in any well-educated person.

The importance of the indicator skills becomes even more apparent when we think about what happens in their absence:

- What kind of a society do we have when its citizens don’t explore the world with curiosity?

- What if we never identify and analyze our own perspectives and influences?

- Who benefits or suffers if we do not listen actively to others and engage in civil discourse?

- How is our greater society affected if we don’t empathize with one another?

The answers to these questions are not difficult to imagine.

I can think of no better way to make clear the need for the so-called “soft skills” taught in the liberal arts and humanities than to interrogate and reflect upon the real-world value of the indicator skills related to the four domains of global competence. This is what we do in the humanities and the liberal arts, even in the face of being told that our disciplines are irrelevant.

We teachers are often told that students need to leave our classrooms with 21st-century skills in order to have a chance at resolving some of the issues they will face in the world they are to inherit. The need for a powerful and flexible skill set is apparent. What those skills are has not been made so apparent.

I say those skills are the global competencies.

Students are told that they should read widely, write clearly and effectively, and think critically, but the reasons given for this need can be rather esoteric. In high school, students are told they need these skills for college; in college they are told they need these skills for their higher-level classes, then, to impress employers.

While all these things may be true, what we should be telling them is something quite different.

We should be telling them what Howard Gardner says in the preface for Educating for Global Competence, that “young people need to understand the worldwide circulation of ideas, products, fashions, media, ideologies, and human beings. These phenomena are real, powerful, ubiquitous. By the same token, those growing up in the world of today—and tomorrow!—need preparation to tackle the range of pervasive problems: human conflict, climate change, poverty, the spread of disease, the control of nuclear energy.”

We should tell students that reading, writing, thinking critically, and communicating effectively build global competency, that global competencies are super powers, that they are needed to save the world.

Mastering global competencies alone won’t do, however. Those skills and competencies need to be pointed in a meaningful direction. This is where the fourth domain of global competency comes into play.

The Global Education Project makes a direct link between the skills built into the domains and indicators of global competency to an actual mission to transform and save the world, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, “a call for action by all countries—poor, rich and middle-income—to promote prosperity while protecting the planet. They recognize that ending poverty must go hand-in-hand with strategies that build economic growth and address a range of social needs including education, health, social protection, and job opportunities, while tackling climate change and environmental protection.” (Source: United Nations Sustainable Development Goals)

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals may seem overwhelming, but they are goals that matter; they are addressable on the local, regional, national, and global level. If we are not teaching young people to use their education to take action—to work toward solutions to ubiquitous problems and improve conditions in the world—what are we teaching them to do?

“Globally competent individuals are aware, curious, and interested in learning about the world and how it works. They can use the big ideas, tools, methods, and languages that are central to any discipline (mathematics, literature, history, science, and the arts) to engage the pressing issues of our time. They deploy and develop this expertise as they investigate such issues, recognizing multiple perspectives, communicating their views effectively, and taking action to improve conditions.”

—Veronica Boix Mansilla & Anthony Jackson

If students are not learning to engage in a meaningful and active way with the issues of our time, they are not learning the skills they need to live in the world they will inhabit.

Going forward, I know that my task is to front load the global competencies and their importance—even as I’m trying to teach to my courses’ student learning outcomes (which are often focused more on formal conventions).

This summer break has already given me the ability to step back from day-to-day interactions and refocus on my greater purpose as a teacher—to release my students into the world well-prepared to understand, shape and change it.

Online Resources

California Global Education Project

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

Educating for Global Competence: Preparing Our Youth to Engage the World

Kylowna Moton is an Assistant Professor of English at LA City College, and she taught English in the LAUSD for over 20 years. She is a member of the NCTE Standing Committee on Global Citizenship. Her research interests include everyday rhetoric and decolonizing the classroom as a means promoting lifelong literacy to reluctant and emergent readers and writers. Kylowna is an avid traveler and sees her work as integral to her experience of the world and its people.

“The Standing Committee on Global Citizenship works to identify and address issues of broad concern to NCTE members interested in promoting global citizenship and connections across global contexts within the Council and within members’ teaching contexts.”