This blog post was written by NCTE member Trevor Aleo.

In a 1985 interview published in Language Arts, Paulo Freire claimed that if citizens are to be successful, they must learn to read their world as well as they read the word.

It’s an idea I’ve always found fascinating, as well as one that I believe is increasingly important in our digitally driven culture. After all, in the age of smartphones and 5G, we carry “the world” in the palm of our hand and spend quite a bit of time staring at it.

This is especially true of teenagers. The latest research on the media habits and screen time of Generation Z shows just how integral a role technology plays in their day-to-day experiences.

Considering the amount of time spent on devices, the effects of technology on teens can’t be overstated. It’s not only how they communicate (or don’t), but how they construct their sense of self—cultivating identity through their curation and creation of multimodal posts, designs, and content. More and more of teens’ lives and experiences are mediated by online platforms amidst a churning flood of images.

Our conception of the world has also become inexorably bound up in the media in which it is presented. This has far-flung consequences that we’re only just beginning to understand. Our students don’t follow the news by reading the paper, but by watching YouTube, tracking Twitter, and scrolling through Instagram. They aren’t alone either. Most Americans now prefer watching the news as opposed to reading it and a rising number of them get that content online. Like it or loathe it, the texts through which our culture communes and communicates are becoming increasingly visual.

Broadening Our Understanding

Frank Serafini, author of the fantastic “Reading the Visual,” refers to these print, visual, and video combinations as “multimodal ensembles” to capture the fact we rarely encounter information in a single mode anymore.

Whether we’re viewing a snapchat or reading an online article, most of the texts we engage with convey meaning across several modes that shape the meanings within.

As English teachers, this should give us pause. Should we broaden our understanding of literacy beyond a simple cognitive skill if that’s the case? Should we begin to also regard it as a “set of cultural competencies for making socially recognizable meanings by the use of particular material technologies” (Lemke, 1998) to modernize our conception of literacy? Considering the prominent role these ensembles play in our culture and media, one could make a compelling case that they’re deserving of more attention in our core literacy curriculum.

This case is strengthened by Bill Cope & Mary Kalantzis, two eminent experts in the intersecting fields of literacy, semiotics, and instructional design. It’s their belief that we need to consider and integrate new forms of literacy that “will be essential in creating new or transformed forms of employment, new ways of participating as a citizen in public spaces, and new forms of community engagement.”

There’s a lot of empty rhetoric about 21st century skills but having read their 1,000-page multimodal manifesto, “Literacies,” I believe their message is one with real substance and vision. I strongly subscribe to their assertion that “if our learners become good at navigating across different contexts of language use, they will be good at living in a highly interconnected, globalised, multicultural world” (Cope & Kalantzis, 2012).

They’re not alone in that belief either. There’s already been a shift in English language arts curriculum over the last decade or so to account for this expanded view of literacy.

Although the print-based goals of traditional literacy are still rightly front and center, English teachers are becoming responsible for a growing number of other tangentially related domains of knowledge—media literacy, cultural studies, art and film criticism, and so on.

Leveraging Multimodal Literacy

I understand how integrating insight from these new domains sounds daunting and time consuming, but it doesn’t have to be.

Much the same way that understanding history and psychology can enrich our ability to identify themes and analyze characters, borrowing concepts from fields like semiotics can help us more effectively teach content already present in our curriculum. It’s still early days, but there’s some compelling scholarship exploring how multimodal literacy can be leveraged to both support and challenge students by affording them a broader set of meaning making tools.

Despite my enthusiasm, there are some clear challenges that are often ignored when it comes to multimodal literacy in the ELA classroom. For instance, Serafini believes that “teachers are rarely, if ever, exposed to these fields of study [art history, semiotics, media, culture studies, communication studies, graphic design, typography, photography, and advertising] in their certification coursework, graduate degree programs, or professional development workshops” (Serafini, 2013).

Obviously, this is a problem. Considering the prominence of multimodal targets and standards in modern curriculum (just check the new IB Diploma Program Subject Brief), this knowledge gap seems to be an area of critical need.

I believe this gap is one factor contributing to the ubiquity of what my buddy Dan Ryder refers to as “dumpster projects.”

Without the knowledge necessary to make students’ understanding of multimodality deep and transferable, we often fall prey to assigning watered down arts and crafts in the name of creativity, even in high school. It doesn’t matter how flashy the final outcome is, creative busy work is still busy work. We need to give students agency to create texts, but we also must challenge them to critically engage with the design process, not mindlessly complete tasks and construct products.

Honing a Sense-Making Skillset

Multimodal literacy isn’t about pretty pictures and popsicle sticks. It’s not about Pinterest Pedagogy. It’s about honing a sense-making skillset our students can use to navigate the complex times in which we live.

It’s not just academic or theoretical either. I use it to plan units with my colleagues, design slide decks, and create manipulatives. My students use it to communicate complex ideas, plan essays, collaborate on group projects, take notes, and more. It’s a tangible set of tools that can be leveraged in countless contexts.

To illustrate, here are examples of recent student work from this year’s projects:

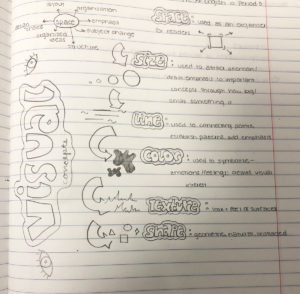

Visual Concepts: We begin the year by learning about and applying some baseline concepts.

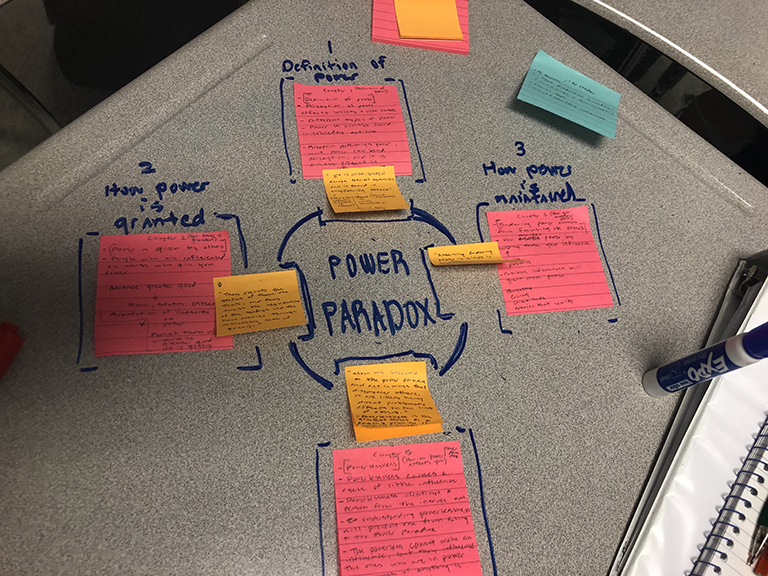

Making Sense of Texts: Students are able to use visual thinking as a tool to organize and communicate their understanding of complex ideas and texts.

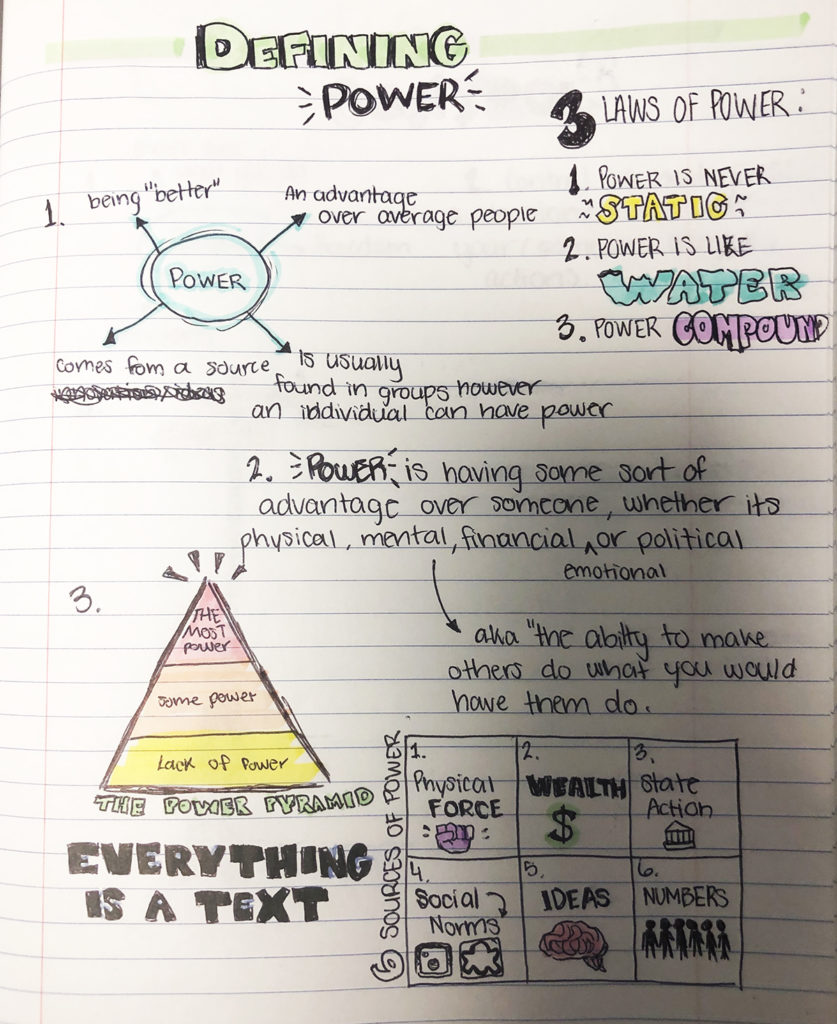

Taking Notes: Visual thinking provides students with a utility belt of knowledge and procedures they can use to be more effective note takers.

Student Covers: Students created a cover to accompany their short story in which they leveraged knowledge of design concepts.

If you’re interested in exploring multimodal literacy in your classroom beyond the resources I’ve shared here, the New London Group’s article “Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures” is a great jumping-off point.

References

Lemke, J. L. (1998). Metamedia literacy: Transforming meanings and media. In D. Reinking (Ed.), Literacy for the 21st century: Technological transformation in a post-typographic world (pp. 283–301). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Kalantzis, M., Cope, B., Chan, E., & Dalley-Trim, L. (2016). Literacies. Port Melbourne, VIC, Australia: Cambridge University Press.

Serafini, F. (2014). Reading the visual: an introduction to teaching multimodal literacy. New York: Teachers College Press.

Trevor Aleo is an English teacher in the DC suburbs. He received his MA in teaching from James Madison University in 2014. He has a passion for innovative teaching practices, finding the intersection between pop culture and pedagogy, and incessantly asking his students “Why?” You can find him pontificating on the state of American culture and education on Twitter @MrAleoSays.