This blog post by NCTE member Frank Baker appeared originally on MiddleWeb on 11/14/21, and is reprinted with permission.

In my media literacy posts, I’ve often written about how popular culture (movies, TV, film, magazines, etc.) as well as current and historic events (elections, the pandemic, civil rights, etc.) can be used by teacher/educators to meet teaching standards and help students better comprehend what it means to be “media literate.”

Our students—the social media generation, often glued to their mobile devices—are exposed to countless media messages every hour. Everyone, it seems, wants their attention.

With disinformation, fake news, and malicious clickbait exploding on social media, evaluating media messages has become one of the most important and relevant 21st century skills. Yet, in a Common Sense Media 2017 report, News and America’s Kids, less than half of young people aged 10–18 agreed that they know how to distinguish fake news stories from real ones.

Are your students media evaluators? Do you feel prepared to teach them?

Evaluating a Media Message

One of the earliest definitions of media literacy was: “the ability to access, analyze, EVALUATE and create media in a variety of forms.” (Source)

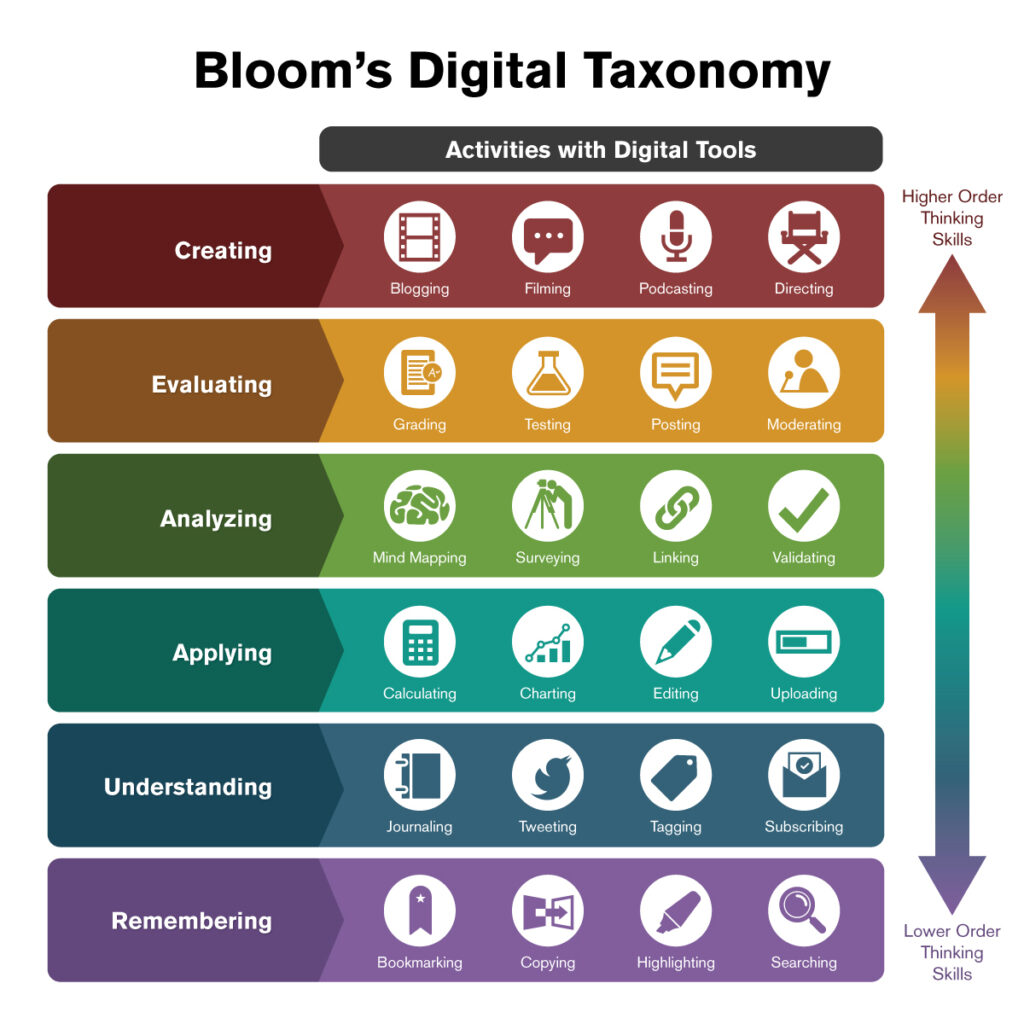

Evaluation also holds a prominent position in the Bloom’s Digital Taxonomy of higher order thinking skills (HOTS) which places evaluating near the top, just behind creating.

Source: Arizona State University (Infographic by Ron Carranza)

So what does it mean to “evaluate” a media message? A writer for the Poynter Institute, a Florida-based journalism organization, recommends these six questions as the basis for evaluating media:

- Who created, or paid for the message?

- Who is the target audience?

- What is the product?

- What are the direct messages?

- What are the indirect messages?

- What is omitted from the message? (Source)

I would include another question to add complexity and push student thinking even further:

- Who benefits from the message?

Media Evaluation in the Classroom

Every time you use images or video in instruction, you have opportunities to engage your students in critical analysis and evaluation skills. You also have the chance to increase their “visual literacy” skills as they learn to “read” media.

I frequently use ads (print and non-print) in my workshops because they are so pervasive. I like to demonstrate how to help students “read” these highly persuasive and influential messages. Incorporating them into instruction is another way of introducing the media literacy/critical thinking questions we want students to think about.

I’m using advertising here as the jumping off point for you to consider the seven questions I’ve shared above.

1. Who created/paid for the message?

During a summer media literacy course I was teaching, I asked educators to select a media sample (one chose an ad for Ford automobiles) and apply the media questions. When answering “who created the message” one teacher thought it was Ford Motor Company. I had to correct her: Ford did not create the ad, but rather hired experts in advertising and marketing to create the ad.

She had not considered that distinction, and I’m guessing most students won’t either. Often we don’t know the name of the ad agency that created the ad, unless we research among the trade magazines, like Advertising Age.

This distinction between manufacturers of products and promoters of those products is another reason to teach students not only how ads are produced, but also the argument or technique of persuasion being used to convince/persuade the buyer. (Learn more about ethos, pathos and logos in this ReadWriteThink article “Persuasive Techniques in Advertising.”)

2. Who is the target audience?

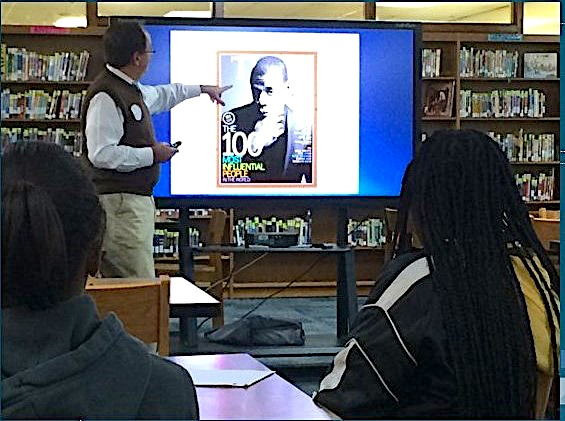

During a workshop with middle school students, who were each assigned magazine covers to examine, I introduced the word “demographic” and the phrase “target audience” and challenged them to identify exactly who (age, gender, ethnicity) the magazine was trying to reach with their advertising. Many students did not know. Would TIME magazine featuring Jay-Z on the cover appeal to them, or to someone else?

When some of the middle schoolers had trouble identifying the magazine’s audience, I suggested that they open the magazine and consider two or three of the ads in it. That simple exercise helped many of them recognize the intended audience for the magazine’s marketing.

A political campaign ad, aired during an episode of ABC’s Black-ish sitcom (for example), is designed to appeal to viewers the advertiser knows are sure to be watching. It’s known as “targeted advertising.” (Read how advertiser Proctor & Gamble bought its way into the show in 2018, in what trade publication Variety described as “an effort to align with consumers who have grown increasingly resistant to traditional commercials that shovel sales talk into lives that are already busy.”)

Most media message creators are always considering: Who am I trying to reach AND how can I get my product in front of their eyeballs. And speaking of attracting eyeballs, the annual Super Bowl football game regularly attracts more than 100 million people in the United States, and lots of time and attention is given to the products. (Read my post about teaching with Super Bowl ads.)

3. What is the product?

Have you ever watched a commercial and were perplexed because it wasn’t obvious right away what they were selling?

I frequently use this almost 3 minute long commercial entitled JOURNEY to promote a discussion of this type of advertising. (I don’t reveal that the ad is sponsored by Louis Vuitton, the high-end luxury fashion maker.)

As you watch the ad it’s not immediately clear what’s being sold: we’re simply exposed to beautiful (and sometimes disturbing) images while being influenced by meditative music playing in the background. It’s not until near the end of the long commercial that we begin to get glimpses of the product. Even then it’s subtle.

The ad is meant to convey the “true and rich essence of travel as a process of both discovery and self-discovery” according to the head of communications at Louis Vuitton. (Source) Did this spot seem “hypnotic” or make you feel relaxed or suspended from reality? That’s one of the goals. This writer suggests we are more vulnerable in this state.

Did people immediately purchase a Louis Vuitton handbag after watching this ad? Probably not. But it might make some feel an emotional connection. This spot highlighting the accomplishments of women in sports, which ran during the 2021 summer Olympics, offers another example where the product is not evident until the conclusion.

To go even deeper, media literacy invites us to consider that WE are the products being constantly sold to companies by media marketers. Companies want to create a connection, a bond, so that we might become brand loyal, life-long customers—and they hire marketing experts to help make that happen. (Read more about this idea here.)

Even today, as information shifts from traditional TV formats to streaming and platforms like Instagram, TikTok, etc., the information much of us share via social media is fodder for advertising and marketers, who then use that information to deliver more targeted and tailored ads to us. Students’ privacy and the need for marketing transparency are issues that could be considered here.

4/5. What are the direct/indirect messages?

Direct messages make it clear who or what is being sold; indirect ones are not so obvious.

The Vuitton JOURNEY spot is a perfect example: it’s clear (when you realize who the advertiser is) that they are selling expensive products to customers who can afford those products. But asking students “what else is being sold” can generate a lively discussion.

Politics is often about indirect messaging. A commercial for a political candidate might incorporate images such as the American flag, a family picnic, people singing in church—all designed to associate the candidate with American values. That symbol placement is not by accident. [For more about this, see my website The Role of Media in Politics.]

This is one of my favorite questions and I use it often in my media literacy workshops.

6. What is omitted from a message?

In an activity where I distribute tobacco ads from magazines, I ask students “what are you not told?” It’s fairly obvious what Big Tobacco omits. And students will use their prior knowledge about the dangers of tobacco products when they are given an opportunity to create a “counter-ad.” I guarantee they will be creative in their media productions. [Read more about my tobacco ad activity here.]

How often does a car commercial reveal exactly how much the car costs? Why would prescription drug companies withhold what a drug might cost? There are so many examples here to consider, and of course your students can research the answer to what’s not evident.

Chase First banking video

This activity might engage your students. Have them watch this 45-second ad for the Chase First Banking debit card for kids aged 6–17 on YouTube. Although the ad is aimed at parents and guardians, rather than children themselves, have students watch the commercial several times and take notes listing questions they have and statements in the ad they wonder about. What’s omitted? How can they find out the answers? (This Chase webpage can be a teacher resource.)

7. Who benefits from a media message?

This is another of my favorite questions that students rarely consider. Here’s an idea for you to try with your students.

Remember advertisers want to get their product as close as possible to their customers. Many of us can relate to this scenario: standing in a long line waiting to check out at the grocery store.

Did you ever consider why those magazine racks are positioned there? How often have you picked one up, flipped through it, deciding whether to put it back or buy it?

Another favorite question of mine, perhaps as I’m browsing the aisles at my local Barnes & Noble where literally hundreds of periodicals are on display, is this: Who benefits when I purchase one of these magazines?

First, I would want students to define the word benefit. From there, encourage them to brainstorm “who benefits.” Have them make a list and challenge them to come up with more than 10.

Why Is All This Important?

Evaluating media messages like advertising is another way to help meet all-important literacy learning standards.

Increasingly today, students are the targets of advertisers (and influencers—a whole other topic for future consideration). Introducing the “media literacy” questions is an appropriate way to ignite their critical thinking skills and to get them in the habit of always considering those questions.

Advertising, in many ways, does not want us to “think”—rather it wants us to feel. It is those emotional connections that often get us to remember the product and commit to make a purchase.

I’d appreciate hearing from you about how you incorporate the media literacy questions when you have your students consider evaluating a media message. I trust it will be rewarding: for you and them.

Resources

Critically Analyzing Media (KQED)

https://microcredentials.digitalpromise.org/explore/critically-analyzing-media-2

Critical Media Literacy: Commercial Advertising (Lesson plan)

https://www.readwritethink.org/classroom-resources/lesson-plans/critical-media-literacy-commercial

Social Media Influencers: Who Do We Trust Online?

https://www.middleweb.com/42047/social-media-influencers-who-do-we-trust-online/

“What Are They Selling” Exercise

https://gestureandmeaningblog.wordpress.com/coursework-exercises/part-four-advertising/project-selling-the-product/exercise-what-are-they-selling/

Admongo (Federal Trade Commission) Lesson Plans/Activities

https://www.consumer.ftc.gov/Admongo/_pdf/curriculum/FTC-Lesson-Plans-Student-Worksheets.pdf

Use Print and TV Ads As Informational Texts

https://www.middleweb.com/43732/use-print-and-tv-ads-as-informational-texts/

Media Literacy: Teaching Kids About Political Ads

https://www.middleweb.com/43459/media-literacy-teaching-kids-about-political-ads/

Using Super Bowl Ads In The Classroom

https://www.frankwbaker.com/mlc/super-bowl-ads/

Frank W. Baker conducts professional development workshops both face-to-face and via webinar and virtual workshops. His most recent book Close Reading The Media was praised as “an incredible resource for any middle or high school humanities teachers looking to teach students how to think critically about the media they regularly consume.” Follow him on Twitter @fbaker

Frank W. Baker conducts professional development workshops both face-to-face and via webinar and virtual workshops. His most recent book Close Reading The Media was praised as “an incredible resource for any middle or high school humanities teachers looking to teach students how to think critically about the media they regularly consume.” Follow him on Twitter @fbaker

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.