From NCTE’s Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC) Disability Studies Standing Group.

This post was written by NCTE member Dale Katherine Ireland, who is also a member of the CCCC Disability Studies Standing Group.

Rolling to the classroom

No ramp

No ramp (oh no)

Prof ain’t got the slides

Feeling cramped

Feeling cramped (yeah yeah)

They say “work harder”

just can’t stand

Can’t stand (uh huh)

No voice

No choice

Gotta take a stand

Take a stand

–“Bad Accommodations” (Disability Pride Anthem)

Last month was Disability Pride month, and as I reflect on it now as a disabled person, I feel many things: activism, celebration, and, yes, exhaustion. This month brought a surge of recognition, advocacy, and opportunities. There were more talks to give, articles to write, and opportunities to avail, such as an inclusive online

bachata dance class. I participated in the dance class from my bed. The instructor shared the dance’s rich history, described and demonstrated different ways of performing each movement, while captions, ASL interpreters, and supported chat ensured everyone could participate. More classes like this please! Beyond immediate celebrations, Disability Pride Month also opened doors to speculative futures, inviting us to communally imagine: What if things were different?

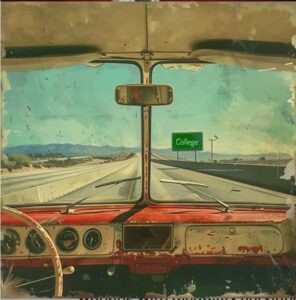

Living with chronic inaccessibility, I have often contemplated a world in which difference is not treated as an exception. Before I dropped out of high school, I was in a mix of AP, special ed, and other classes. My non-special-ed teachers accused me of not trying hard enough. They reprimanded me for not focusing more, for how slowly I read and wrote, and for my “abhorrent” spelling, all of which were understood as moral failings on my part. I was told to focus more, stop daydreaming, keep up, pay attention, sit still, look at me when I am talking to you, stop being careless, and do better. Several were incensed that I was in special ed and AP classes. As a high school dropout, with then undiagnosed learning disabilities, I remember fantasizing about school. When my partner and I would drive down to Los Angeles to visit family, an exit sign for a community college would spark imaginings of how to return to education. How could I someday take that exit to college?

ID: Starting from inside an old van, including the steering wheel to the left, a dashboard, two visors above the split window windshield, a rearview mirror, two windshield wipers problematically inside the bus, to which we might shrug and move our attention beyond the windows. The van drives down Interstate 5 in California. A green sign with white letters says, “College” on the right side of the Interstate. The vista fills with distant hills at the horizon and desert-like landscape on either side of the Interstate. The sky is blue with a few clouds to the right. The image is faded and has distressed edges like a favorite worn photograph. I co-created the image using my memory, Midjourney, my iPhone photo app, and Snapseed.

Years later, after my partner’s welcoming my curiosity about his high school algebra book and the open doors of the Berkeley Adult School, where I eventually earned my GED, I took the highway exit to community college, at which I was eventually diagnosed with learning disabilities. I transferred from community college to a four-year college.

As a University of California, Berkeley undergraduate, my favorite rhetoric professor invited me to his graduate seminar because he thought I was better suited for graduate-level work. Despite attending a few enlightening sessions, the department advisor dropped me from the course, citing my “incomplete” grades. While I was lectured on my moral failings, I was advised once again not to take my reduced course load accommodation. I needed to step it up, get serious, and remember I would not get “help” in the real world. Noted. I was the problem.

This pattern of misunderstanding and resistance to accommodations was not limited to administrative decisions; it extended to the classroom environment as well. One professor sat me outside of class, in a busy hallway, as an alternative quiet testing environment accommodation for an exam. It was an uncanny accommodation at best and representative of many more accommodations to come.

ID: A student, wearing a light shirt, dark vest, and dark pants, sits at a small desk in a hallway teeming with students while writing in a notebook—trying to take an exam. I co-created the image using my memory, Midjourney, my iPhone photo app, and Snapseed. You might be wondering why I keep including such poorly composed images and the song in the introduction. I’ll explain, just not in this moment.

While Disability Services and some faculty offered support, the systematic dismantling of my accommodations forced me to struggle forward as I was pushed back. These subtle, counterproductive accommodations were imperceptible to others unless I expended additional effort to expose and challenge them—effort that would have detracted from my academic work. While I fought for some accommodations, I often chose to channel my energy into my ethnic studies and rhetoric classes instead. Despite these challenges, like the complex dynamics of Disability Pride Month—which balances celebration with advocacy while raising awareness—there were aspects of my undergraduate education I do cherish.

As a student, I excelled academically when I had my accommodations and was deeply involved in campus life. My work was recognized with scholarships and even mentioned in a speech by Chancellor Tien. I served as a teaching assistant for a rhetoric class, sat on several university committees, and co-coordinated the student transfer center. Outside the classroom, I played women’s water polo and served on the disability services student advisory board.

The joyful part of my relationship with reading and writing was evident in my roles as a writing tutor, president of the rhetoric association, and frequent library user with a coveted stack pass. I found joy in both writing and literature and discovered a love for ethnic studies and rhetoric. However, as a disabled student, I constantly faced difficult choices about what to sacrifice or miss out on. Rarely was I allowed to fully choose anything. In these challenging moments, I found solace and guidance in the words of my professor, June Jordan, who taught me a powerful coping mechanism: write about it. And here we are.

My experience isn’t unique; even today, the dropout rate for high school students with disabilities is nearly double of that of non-disabled students. Recognizing this systemic issue, I sought ways to address it. Through collaboration, I realized we achieve better results when thinking collectively and developing solutions that include everyone.

Well-intentioned educators often modify their existing curriculum to accommodate students with disabilities. However, these modifications are typically afterthoughts. Jay Dolmage calls these retrofits

: “we retrofit our structures for access, we add ramps at the sides of buildings and accommodations to the standard curriculum—still, disability can never come in the front door.” This retrofitting approach creates a dichotomy of “us” and “them,” where courses are designed for “us” and modified for “them.” As someone who is both “them” and “us,” I want to imagine classes as spaces with accessible “front doors”—environments we can all enter and inhabit together. I also want us to be able to go together in the way Mia Mingus describes: “I want to be with you. If you can’t go, then I don’t want to go.”

ID: A group of smiling disabled college students moving through an open door. Students are walking and one student is using a wheelchair as they move through open doors into bright sunshine. The style is oil painting with visible brush strokes and bright reds, blues, greens, reds, and yellows. I co-created the image using my memory, Midjourney, my iPhone photo app, and Snapseed.

Togetherness in education transcends physical proximity and synchronicity. There are myriad ways to connect and cultivate a sense of community. It also does not imply a uniform approach to language use and practice. Linguistic justice, as conceptualized by April Baker-Bell, promotes an equitable, anti-discriminatory framework for teaching language and literacy. Baker explains that “The belief that there is a homogenous, standard, one-size-fits-all language is a myth that normalizes white ways of speaking English and is used to justify linguistic discrimination on the basis of race.”

Ironically, many well-intentioned educators who modify curriculum for accessibility expect students to do the same with their language—to alter it. In essence, they are asking students to suppress their authentic selves. Gloria Anzaldua explains how language discrimination harms: “So, if you want to really hurt me, talk badly about my language. Ethnic identity is twin skin to linguistic identity—I am my language. Until I can take pride in my language, I cannot take pride in myself.”

Our educational system often encourages students to conform rather than embrace the truth of who they are and who they are becoming. This was poignantly explained by a story shared by Sunn M’Cheaux, the keynote speaker at the 2024 Language Equity in Academia: Reimagining kNowledge (LEARN) Conference.

M’Cheaux recounted an interaction with his former high school vice principal on graduation day. This administrator, previously a guidance counselor, had frequently ordered M’Cheaux to “Pull up your pants.” Similar things were said to M’Cheaux about his language. The vice principal’s past actions along with those of others had sent a clear message: M’Cheaux’s language was inferior, his dress was inferior—he was inferior. But M’Cheaux was also thriving. He explains, that in high school, “I’m a student teacher for the subject that I’m not doing well in because I’ve won the writer conference competition, and that was one of the things that you got to do.” M’Cheaux tells a story of thriving and failing, but what was noticed? His slightly sagging pants.

On graduation day, the vice principal approached M’Cheaux with a series of questions:

“Did you win the wrestling tournament?”

“Yes,” M’Cheaux replied.

“Did you win the writing competition?”

Again, M’Cheaux answered affirmatively.

“Are you going to college?” the vice principal inquired. M’Cheaux admitted he didn’t know how to apply.

At this point, the vice principal—who had rarely engaged with M’Cheaux beyond admonishing his appearance—remarked, “I wish I had known you were smarter sooner.” That last sentence is heavy with centuries. I will be holding that sentence close and learning it in ways I have yet to imagine.

This anecdote starkly illustrates how we often push students to conform rather than celebrate their individuality. We teach our students to fight themselves instead of inviting them to be themselves. By failing to recognize the student who would win the writing competition, choosing to instead fixate on pants, we more than risk stifling students’ potential. We do great harm. Much of what M’Cheaux talked about was recognizing linguistic discrimination and ways we could create inclusive learning ecosystems. I encourage you to read or listen to M’Cheaux’s keynote; I cannot do it justice in this small space.

This call for inclusivity and recognition of diverse voices aligns with broader trends in the field of writing studies. Writing studies has been moving away from upholding ideals of academic standard writing. Mya Poe reminds us that Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC) scholars are shifting away from rigid universal standards and toward a more inclusive approach. Professionally, we are rejecting the idea of a single, correct way to write. We are now concentrating on expanding possibilities for written expression, recognizing writing is a dynamic process that can reflect and incorporate varied cultural and linguistic backgrounds across academic and professional settings.

I have more questions. These are some I am asking myself: Where do I make assumptions about competence, and what is informing those assumptions? Am I policing language, and here does language policing limit access to sources?

As a disabled academic, I still internalize and perpetuate ableism. Working with these and other questions helps me stay curious and create space to learn and keep myself accountable.

As I have been teaching this summer and preparing for the fall semester, I have been talking and working with other colleagues. We increasingly think about AI and equitable communication practices on our students’ behalf. Disability and linguistic justice have remained at the forefront of our considerations. Because human knowledge reflects human bias and AI trains on human knowledge, we must be attentive to how AI perpetuates bias. You may have noticed I used AI for the song hyperlinked in the introduction and that I co-created with AI when I produced images for this post. We have asked or are going to be asking our students to work with AI. How will we know what tools are accessible, what output is accessible, how to read output for bias, and what tools we and our students may use to make our AI output accessible?

To address these barriers and biases, we need practical strategies that promote accessibility and linguistic equity. Margaret Price offers us a valuable approach: access priming. Price explains that “Access priming, as I define it, is making a concrete suggestion about how one might be helpful or supportive—without yet doing it. Both of those italicized points are important.” This concept provides a framework for thoughtfully considering and proposing inclusive practices before implementation, allowing for collaborative refinement and avoiding presumptive action. Applying this framework to our classes reveals its crucial importance: when one of our students does not have access to their accommodations and/or to their language, the entire class faces a shared barrier: access to one another. Pride in our educational practices should stem not just from academic achievements, but from our commitment to creating inclusive spaces where every student’s needs, abilities, and linguistic backgrounds are welcome through the front door.

Dale Ireland (she/they) is a disabled academic specializing in disability studies. She is an adjunct faculty member in the Writing, Languages, and Literature Department at California State University, East Bay, and a doctoral student in English at The Graduate Center, CUNY.

Dale Ireland (she/they) is a disabled academic specializing in disability studies. She is an adjunct faculty member in the Writing, Languages, and Literature Department at California State University, East Bay, and a doctoral student in English at The Graduate Center, CUNY.

Ireland’s research focuses on representations of accommodations and care labor in disability studies. Their current work explores concepts such as “uncanny accommodations,” which are barriers paradoxically presented as accommodations. Her scholarship has been published in Disability Studies Quarterly and Perspectives on Communication Disorders and Sciences in Culturally and Linguistically Diverse (CLD) Populations. They also coauthored the instructor’s manual for the 8th edition of Reading Critically, Writing Well: A Reader and Guide (Bedford/St. Martin’s). In addition to her academic work, Ireland has served as an elections officer for the CCCC/NCTE Disability Studies Standing Group and in other capacities for regional affiliate societies of the American Society for Eighteenth-Century Studies.

Dale Ireland is deeply invested in collaborative curriculum development and design. They specialize in teaching composition courses, disability studies courses, and writing-intensive courses featuring works of 18th and 19th century British literature, contemporary English speculative fiction from the 20th and 21st centuries, and nonfiction.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.