This post was written by NCTE member Miriam Plotinsky.

Gina stares at the essay her teacher just returned. It looks like it’s bleeding, she thinks in dismay as her mind tries to process the comments, acronyms and symbols strewn emphatically across the pages. After a few moments of trying to remember what “awk” stands for, Gina gives up. She’s never been able to do well on her writing assignments, and that will probably never change. On her way out the door, dejected, she tosses the essay into the trash.

Across the room, Gina’s teacher sees her throw the essay in the garbage. There goes a half hour of my time, he thinks in frustration. Why do I bother making the effort to give them feedback if they’re just going to ignore it? Shaking his head, the teacher wonders if there is any way of getting through to his students.

This scenario likely resonates for almost any teacher of writing. Nothing feels more futile than spending hours marking papers only to have students disregard the comments and get stuck making the same mistakes repeatedly. Rather than get caught in an endless loop of angst, there are better ways to provide targeted feedback to students so that they are fully cognizant of where they might be struggling with their writing and be more aware of what they can do to improve.

The Purpose of Feedback

Traditionally, feedback is defined as the information that teachers give students about performance. However, it can be easy to muddy the waters unintentionally by overextending the intention of feedback. According to backward design expert Grant Wiggins, “The term feedback is often used to describe all kinds of comments made after the fact, including advice, praise, and evaluation. But none of these are feedback, strictly speaking.” At first, this statement might seem confusing. If “advice, praise and evaluation” aren’t feedback, what is?

Essentially, feedback is objective information that tells students where their work stands in relation to a stated goal. Suppose a class is finding textual support for literary analysis essays and the stated criteria for success includes the following elements: at least three pieces of directly quoted evidence, a clearly stated connection to the thesis, and a selection of quotations from different points in the core text. If a student only quoted two examples, the product does not yet meet the expressed standard. An example of teacher feedback in this situation would be: “Your essay has two cited textual examples. One more example is needed for this essay to meet criteria.” This fact-based observation is focused on what the student has produced in a transparent way rather than being grounded in unclear language that leaves room for interpretation.

Keeping Guidance and Evaluation Separate

While feedback needs to remain free of judgment and focused on facts, there is a place in writing instruction for guidance and evaluation. Consider the example above in which a student has neglected to cite a third example. The feedback points out that discrepancy in relation to the criteria for success, but the teacher should probably then move into providing some suggestions (i.e., guidance) for improvement such as, “You might want to look at Chapter Three. The character has experiences that support your argument throughout that portion of the book.” That way, the student has some guidance from the teacher in figuring out how to meet the provided expectations.

Evaluation usually takes the form of a grade and presumably, the criteria for success represents the highest point on a rubric. If an ideal essay is scored with the number four, the student who has not yet included enough examples in her product might be scored more toward the number three, which could translate roughly to a “B.” Regardless of the specifics, a grade should be a transparent reflection of student success in relation to the criteria. Otherwise, the evaluative process loses its meaning and more importantly, students are unaware of how they should improve their writing without the necessary clarity.

Keeping both guidance and evaluation separate from feedback helps to build the sort of “no-secrets” classroom that is ideal. If a criteria for success checklist is provided both with every writing assignment students receive and then attached to the finished product as a vehicle for teacher feedback, two separate areas can be provided below, one for brief suggestions that can help students meet the missing criteria and a second for the grade itself. This practice will help to keep the three categories of feedback, guidance and evaluation connected but distinct.

“Habit Stacking” for Quicker Feedback on Written Work

The theory of “habit stacking,” popularized by the bestseller Atomic Habits by James Clear, describes the practice of building one habit atop another to gradually work toward a goal in manageable chunks rather than trying to achieve a huge shift in behavior all at once. As Clear writes, “It is so easy to overestimate the importance of one defining moment and underestimate the value of making small improvements on a daily basis” (p. 15). For students who are still establishing their writing skills, habit stacking is a powerful tool for providing meaningful but quicker feedback in a way that focuses on improvement in a skill or standard.

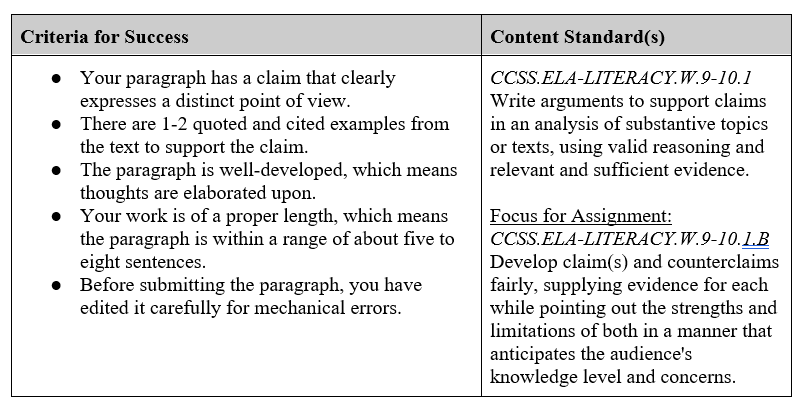

Suppose students have been working on writing paragraphs that have the following criteria for success and relevant standard(s):

Assuming that students have received the information above with their assignment so that they can be aware of the targets for their success from the get-go, the feedback process is all that more transparent, allowing the teacher to pinpoint where the paragraph is not meeting the expected standard more incisively.

Assuming that students have received the information above with their assignment so that they can be aware of the targets for their success from the get-go, the feedback process is all that more transparent, allowing the teacher to pinpoint where the paragraph is not meeting the expected standard more incisively.

So, how can ELA teachers avoid spending endless time in a grading rut and maximize the habit stacking process to ensure that students receive quick, actionable feedback? To develop a more gradual process that gets students used to receiving feedback from a standards-aligned criteria for success checklist like the one above, some possible steps to try might look like this:

Step One: Include a criteria for success checklist with each writing assignment. Get comfortable with this habit before proceeding to the next step.

Step Two: Take five minutes in class to focus on one item from the checklist (prioritize by importance) with students. Explicitly share the purpose of including this information with their assignment.

Step Three: When students complete their assignment after having the conversation in Step Two, provide feedback on just that one area of focus. Ignore the rest of the checklist for now.

Step Four: For the next assignment, go through the entire checklist with students. Ensure that everyone understands how their success will be measured.

Step Five: Provide focused feedback on the criteria. Circle areas for improvement, and make short comments in the checklist section only about how students performed in relation to the identified criteria.

As students become accustomed to this more focused, streamlined process for getting feedback on their work, they will develop a clearer understanding of how their work is assessed. Even more important, they will make more progress when they see that any grade resulting from their performance (the separated evaluation portion, as described earlier) is based on a clear and visible target, rather than on a murky judgment call that could be grounded in personal bias.

Nobody wants to mark up papers for endless hours only to see students throw their papers in the trash. To get out of a vicious cycle, building short but powerful habits over time that transparently show students how they can be successful will yield better results. That way, the painful image of a paper bleeding red can make way for a far more clear and doable feedback process.

Miriam Plotinsky is an instructional specialist with Montgomery County Public Schools in Maryland and the author of several education books: Teach More, Hover Less: How to Stop Micromanaging Your Secondary Classroom, Lead Like a Teacher: How to Elevate Expertise in Your School and Writing Their Future Selves: Instructional Strategies to Affirm Student Identity (W.W. Norton), as well as the forthcoming Small but Mighty: How Everyday Habits Add Up to More Manageable and Confident Teaching (ASCD, 2025). She is also a National Board-certified teacher with additional certification in administration and supervision. She can be reached at Miriam Plotinsky.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.