This blog post was written by NCTE member Jennifer Ochoa as part of a blog series celebrating the National Day on Writing®. To draw attention to the remarkable variety of writing we engage in and to help make all writers aware of their craft, the National Council of Teachers of English has established October 20 as the National Day on Writing®. Resources, strategies, and inclusion in a blog post does not imply endorsement or promotion by NCTE.

This blog post was written by NCTE member Jennifer Ochoa as part of a blog series celebrating the National Day on Writing®. To draw attention to the remarkable variety of writing we engage in and to help make all writers aware of their craft, the National Council of Teachers of English has established October 20 as the National Day on Writing®. Resources, strategies, and inclusion in a blog post does not imply endorsement or promotion by NCTE.

Walking around my classroom last week, I went table to table, checking notebook drafts of kids’ memoirs. As each kid showed me the pages, pointing to where they wanted a teacher spot check, I quietly asked, “Are you pleased with this piece? Do YOU like it?” or “Are you proud of what you’ve written here, does it feel ready to publish?” Every time, the writer paused, looked back at their draft and thought before answering.

Where I teach in NYC, and in many other areas of the country, joyful, authentic aspects of literacy are being squeezed out by “scientific” practices. The writing students produce is responsive writing, analyzing excerpts from longer “rigorous” texts, mimicking the writing on standardized state exams. This isn’t new, it’s been happening in some form for at least the last two decades. Quite frankly, I participate in this myself. I’ve created test-like prompts for the kids in my eighth-grade classes. I ask them to write RATE paragraphs (Restate the question, Answer the question, Text evidence, Explain text evidence), and grade them against test-like rubrics. And, like many, I also push the boundaries of curricular mandates, figuring out spaces that joyful and authentic literacy experiences can still thrive. For instance, on Mondays, we read beautiful or funny picturebooks for our Community Read. Tuesdays and Thursdays are quickwrites in our notebooks, in the style of Linda Reif. And every single day, we hunker down for a cozy 15 minutes of independent reading, surrounded by our classroom library of hundreds of books. We’ve continued, for now, to squish the curriculum aside and maintain a launching unit that concludes with memoir writing. And we still end the year in total kid brilliance, when everyone writes and performs their own TED Talk.

I’ve noticed throughout the years, though, that when we’re writing responsive, formulaic, “schoolish” tasks, the kids’ level of engagement dissipates. Their level of care and thoughtfulness for their writing also dissipates. Has this happened to you? Kids turn in messy, sometimes ripped, occasionally food-smudged analytical response worksheets. Character analysis paragraphs might only be a couple sentences long and may not have carefully checked punctuation, spelling, or capitalization. I encounter less apathy when the writing we are doing is kid based. They’re excited writing drafts of memoirs or short stories or even personal responses to pieces of literature they find engaging. This writing is more thoughtful and carefully rendered. And for me, it’s a pleasure to read.

Years ago, I attended a lecture at Teachers College, Columbia University, featuring Dr. Lisa Delpit and Dr. Christopher Emdin. A notion that wiggled into my teacher brain was the idea Delpit and Emdin posed about creating spaces in our classrooms for kids to be responsible for their own learning, and times during which kids’ excellence is at the center of our curriculum. The scholars encouraged me to think deeply about how I challenge kids in my classroom beyond what is considered traditionally challenging in classroom spaces.

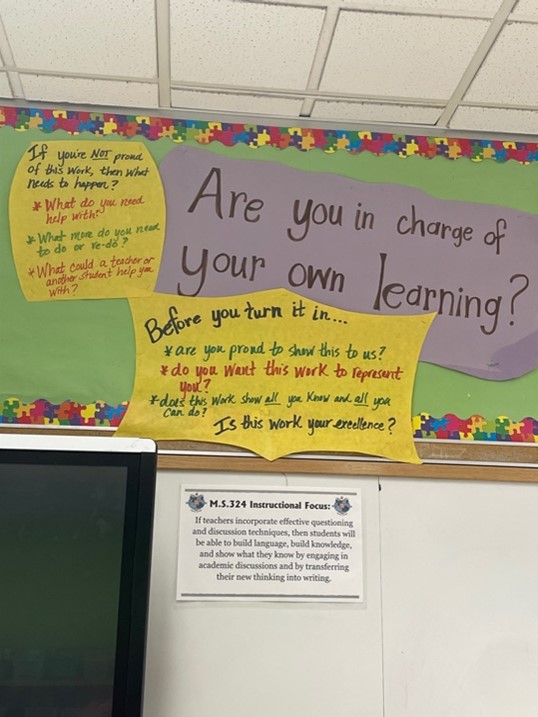

The next morning, I walked into Room A205 and looked around. I considered how what I say and how I frame our work directly impacts how seriously the kids take themselves as readers and writers. I thought about creating the elements Emdin and Delpit suggested. I made two charts that still live in the front of my classroom. The charts encourage kids to consider the work they are turning in. Is it something they are proud to put their name on? Are they proud to claim this work? It was around this time that I began pointedly asking kids, “Are you pleased with this? Are you ready to turn this in?”

Something weird and magical happened when I asked those questions. I assumed most kids would quickly exclaim, “YES!” shove the paper in my hand and be done with the exchange. But what actually happened was kids paused. When I asked, “Are you pleased?” they took a moment and thought. They looked back at their papers, their drafts, their quizzes and tests, and assessed themselves. They considered whether, as a person creating this piece, they were truly and happily done, or if the piece needed more work. After some reflection, kids said, “Yep, it’s ready,” and gave me the work. Or, they shook their heads and said, “No, I’m not ready yet.” Then we’d talk a bit more. I’d counter, asking if they knew what needed to happen next so the work felt done. They almost always knew. They’d explain they needed more details in a certain section, or they didn’t really like how it ended. Often, they needed to go back and check punctuation and spelling. And always when I asked if they had a little more time, would they be pleased, they said yes.

This simple exchange is now our common practice. It takes not more than a minute or two, but it’s changed how the writers in my class consider their writing. It honors the authentic process of going back into a draft and looking with new eyes. Asking, “Are you pleased with this?” rather than, “Are you done with this?” shifts the writer’s focus from completion to satisfaction in their creation. It puts the joyful pleasure of working hard on a piece of writing and feeling proud of what you’ve written back into the center of our writing work.

Jennifer Ochoa has been a high school and middle school ELA teacher for more than 30 years. When she’s not hanging out with eighth graders, she’s sitting calmly somewhere reading a book. Follow her on IG and Threads (@bronxsmiling) for her monthly book stacks!

Reference:

Delpit, Lisa, and Christopher Emdin. 2016. “Teacher as Activist: Bridging the Educational Divide” Lecture, Teachers College at Columbia University, New York, NY, September 21, 2016.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.