This post is written by Bryan Christopher, NCTE’s P12 Policy Analyst from North Carolina

Some seniors catch senioritis. Others convince the federal government to change its immigration policy.

There are times when I teach and students learn. Then there are moments when my students teach me — about myself, my job, and my community.

It started on January 28 when Wildin David Guillen Acosta forgot his book bag. He started his car, ran back to his apartment, and found Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) officers waiting to arrest him.

Wildin is one of hundreds of undocumented students attending Durham’s public schools. He was targeted, arrested, and detained during a series of raids focused on recent arrivals instead of individuals with criminal records or gang ties. Wildin met the criteria: he is a legal adult, arrived in the United States after January 1, 2014, and skipped an immigration court hearing in 2015, resulting in a deportation order.

Word around school traveled fast. Students get arrested all the time, but not kids like Wildin. Yes, he was undocumented, but he stayed out of trouble, played soccer, joined clubs, and was on pace to graduate in June.

So students started asking questions. “Why are schools and churches off limits for ICE but early morning bus stops aren’t?” “Who made the decision to quit targeting undocumented adults with multiple criminal convictions in favor of teenagers with no criminal record and good academic standing?” “Don’t they know that he fled Honduras because a gang threatened to kill him?”

Above all, they asked, “Why Wildin?”

Then it became, “How can we bring him back?”

News of the arrest made local headlines. The media moved on, but Riverside High School students didn’t. They corresponded with attorneys and community organizations; reached out to Wildin’s parents, teachers, and friends; and covered the story in the school newspaper in both English and Spanish. Then they took to social media, gained traction with nearby schools, and earned support from advocacy groups.

On February 3, Durham’s Human Relations Commission asked federal immigration officials to stop deporting young people from the city. A few days later, the City Council followed suit. By the middle of February, Durham’s school board condemned the ICE raids and requested Wildin be released and return to school.

Momentum was building, but changing the minds of federal immigration officers still felt out of reach. From Stewart Detention Center in Lumpkin, Georgia, Wildin requested his schoolwork. Teachers mailed it on February 19, but the center rejected the package. The teachers mailed the work again on March 3, amid increased media coverage and local support, and Wildin received it.

Students signed petitions to give to elected officials. They gathered more than 400 signatures, photos, and videos in three days while advocacy groups and attorneys added their own pressure.

Then Washington called and invited Wildin’s mother and a Riverside teacher to talk on March 10. They delivered the petitions and handed students’ letters to Congressman G. K. Butterfield (who represents Durham’s district) and Deputy Secretary of Homeland Security Alejandro Mayorkas. They spoke with Representatives Alma Adams, Luis Gutiérrez, Zoe Lofgren, and Robert Menendez and with Senators Patrick Leahy, Harry Reid, and Thom Tillis, among others. They shared photos of current and former students, parents, and community members showing support for Wildin through their social media campaigns.

Still, after a day of conversations, his status remained unchanged.

Undeterred, some of my senior newspaper editors, who had been leading students’ efforts throughout, used their journalism skills to up the ante. One asked if she could spend one class period hammering out a guest column for the Raleigh News & Observer. Another asked to work through lunch to edit a video compilation of students advocating for Wildin’s return.

On March 17, a third student asked for an extension on her upcoming prom story deadline so she could join a conference call with the US Department of Education. She, along with students in Charlotte, North Carolina, discussed the ICE raids’ impact on school attendance. They talked about the many undocumented students who had stopped coming out of fear of arrest. This immigration policy, they said, contradicts the Obama administration’s graduation goals. The United States will never get its graduation rate to 90 percent if kids are afraid to come to school.

Later that evening, after Butterfield released a statement detailing his efforts to request

Wildin’s release and supporters rallied in downtown Durham, an immigration judge denied a last-minute request to reopen the case. Wildin was to be deported Sunday, March 20.

The next day in school more than 500 students wore white wristbands in a show of solidarity. They placed more than 100 calls to Butterfield and organized another rally. Hours later, students from several area schools, community members, and advocacy groups marched through Durham and ended at the doorstep of Butterfield’s office. They didn’t leave until they heard from him.

On Sunday morning, after working with Butterfield and Lofgren through the night, ICE Director Sarah Saldaña issued an order to delay Wildin’s deportation. Immigration lawyers planned to seek an appeal and request he be released while they lobby for his asylum, but no one knew how long his deportation would wait.

Twenty-four hours later, the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) extended the hold on Wildin’s deportation order and agreed to reopen his case. The appeal process could take months, during which WIldin will remain at the detention center.

After BIA reopened Wildon’s appeal, I donned a purple ribbon and pledged my support during a district-wide #week4wildin. Students signed more petitions and took photos and videos to send to the Department of Homeland Security, ICE, and President Obama. They also convinced Butterfield to visit our school on April 4, participated in a rally in Raleigh on April 7, and reached out to Hillary Clinton for help.

Momentum slowed after Wildin’s appeal case reopened. Butterfield formally requested Wildin be released from Stewart while his appeal plays out in court, but it was denied by ICE Director Saldaña.

Then the New York TImes added new pressure in an April 20 op-ed about Wildin and other students arrested during the winter ICE raids. Wildin also had a few visitors at Stewart, including journalists and, most recently, his mother. My students continue to advocate, visiting college campuses as guest speakers and communicating with advocacy groups around the country. They don’t plan to stop advocating until Wildin returns to Riverside and graduates.

For me, the past few weeks are not about politics. They’re about watching kids learn how to communicate, advocate, and mobilize for a cause — and person — they believe in. What started as a hot-button issue on the campaign trail became an opportunity for students to become part of something much bigger than themselves.

When I was 18, I struggled to stay awake during morning classes. I stopped doing homework once I was accepted to my top college choices and filled the extra time hitting baseballs on an empty field. It still takes me days to write a column, and I’ve never spoken to anyone at the US Department of Education. As I watched my students rise to the challenge, I realized they didn’t need me anymore. At the expense of a prom story deadline, I got out of their way.

My school days will return to normal soon enough. I’ll keep teaching writing, literature, and journalism in the most engaging ways I can. It won’t be anything like the past few weeks, but I take great satisfaction in knowing that my students possessed skills they needed when the time came to persuade others urgently and peacefully.

Most of all, this experience has taught me that when kids find something they really believe in, teachers should stay out of their way. My students have shown me why I teach in the first place: to deliver instruction, provide support, and, most important, step aside when they’re ready to lead.

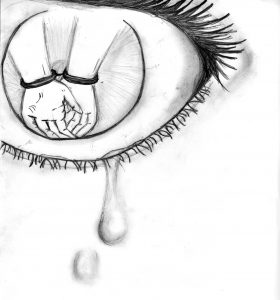

Note: The cover artist is Margot Gersing, junior at Riverside High School.

To learn more about Riverside students’ efforts to bring back Wildin, read the March and April issues of The Pirates Hook newspaper and follow #RHSwantswildinback, #freewildin, and #educationnotdeportation.

Bryan Christopher teaches English and Journalism at Riverside High School in Durham, NC. He’s also an NCTE Policy Analyst and Hope Street Teacher Voice Fellow. Email or Follow him @bryanchristo4.

Bryan Christopher teaches English and Journalism at Riverside High School in Durham, NC. He’s also an NCTE Policy Analyst and Hope Street Teacher Voice Fellow. Email or Follow him @bryanchristo4.