This post is written by Bryan Christopher, NCTE’s P12 Policy Analyst from North Carolina. It is the second part of a series about Wildin Acosta, an undocumented student. You can read the first part here.

On January 28, Wildin Acosta, an undocumented high school senior in Durham, NC, was arrested on his way to school. On August 29, he returned to school again, thanks to the advocacy efforts of his teachers, community, and, most of all, classmates.

In part one I wrote about the demonstrations, articles, conversations with lawmakers, and social media campaigns my student-advocates organized to halt Wildin’s deportation. But shortly after, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) Director Sarah Saldaña denied US Congressman G. K. Butterfield’s request for Wildin’s release from Stewart Detention Center until the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA) reached a decision on his case. It effectively ended his opportunity to finish the final semester of his senior year and graduate, and my students’ momentum slowed considerably.

With an unrelated trip to Washington, DC, on my own schedule, I offered to advocate on their behalf during a few spare hours near the White House. They made a few calls, sent several emails, and handed me a stack of papers, delivery route, and list of instructions a few hours later.

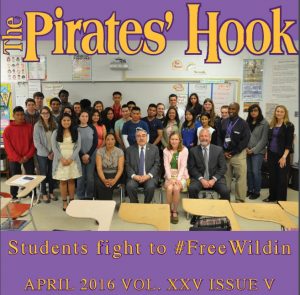

I landed in Washington the next morning, caught the train to Butterfield’s office, and met with Kyle Parker, one of his assistants. I handed him a few copies of The Pirates’ Hook, our school newspaper, with a photo of Butterfield’s visit on the cover. As Parker paged through the issue he noticed several articles written in both English and Spanish. It opened up a wider conversation about how much Durham has changed in the past 15 years and what makes it unique from other communities in North Carolina.

He didn’t have much to offer about Wildin, other than Butterfield’s slow-moving plans to visit Stewart. But he did say that, during the six years he’d spent working in Washington, he’d never seen anything like this before.

“Let’s be clear,” he said. “If it wasn’t for those kids at Riverside, Wildin would already be back in Honduras. There’s no doubt in my mind.”

“Americans see our government as this big, lumbering machine,” he went on. “It’s slow moving but steady by design. These kids, what they’ve done . . . it stopped the machine, if only for a minute.”

“They don’t know that yet,” I said. “Someday they’ll realize the magnitude of what they’ve done, but right now they just want Wildin to graduate.”

From Butterfield’s office I walked to a nearby cafe to meet Julie Mao, a deportation defense attorney with the National Lawyers Guild and member of Wildin’s legal team. She was star-struck to see so many student-advocates on the newspaper cover with Butterfield.

“We should bring them up here,” she said. “Let the press know. Get Butterfield to help.”

“It would be a great opportunity,” I said, “but funding could be an issue, and exams begin soon.”

She said she’d look for funding and let me know. In the meantime, she asked that, during my visit to the White House for President Obama’s Teacher Appreciation assembly, I hand lawmakers a folder filled with letters, a New York Times editorial about Wildin, and the April issue of The Pirates’ Hook.

“If you meet President Obama,” she said. “You can put this on his radar.”

We finished our coffee and she helped me hail a cab to the White House. After moving through seven security checkpoints, I walked past the president’s home movie theater toward the East Wing of the White House. I checked my coat and, watching the other teachers head empty-handed toward the reception, left my bag and Julie’s folder, too.

As it turned out, I couldn’t have made the hand-off, anyway. President Obama spoke to a small group of us for almost an hour, but only the front rows got handshakes. I missed him by fifteen feet.

After the assembly we were allowed to explore the East Wing. I grabbed a drink, meandered through the Green Room and bumped into Secretary of Education John King. He was taking a selfie with another teacher, and I was next in line.

King had met another Riverside teacher the week before during one of his “Tea with Teachers” events. After posing for my photo I thanked him for taking the time to speak with my colleague and listen to Wildin’s story.

King told me that he appreciates the work my school and students are doing to advocate for Wildin’s return. He said he’s reached out to Secretary of Homeland Security Jeh Johnson, but immigration policy is complicated and his hands are tied when it comes to making exceptions for individual students.

It was a more personal answer than I’d expected, but not good enough for my students.

“I understand, Secretary King,” I said. “But if you’d like another perspective, I have some students who would love to discuss it with you.”

He paused.

“You know,” he said, “we do invite students to share their perspectives on policy, and it would be an appropriate setting for their stories. Get in touch with the Department of Ed and see if we can set it up.”

I thanked him, finished my tour of the East Wing, and caught a flight home that night. Before falling asleep I emailed Julie, apologized for not delivering the folder, and asked her to check about that funding.

The next day at school I asked my students if they’d be interested in visiting DC, contacted the Department of Ed, and discussed fundraising options.

To be continued…

Note: The cover art is by senior Emilee Bachman.

Bryan Christopher teaches English and Journalism at Riverside High School in Durham, NC. He’s also an NCTE Policy Analyst and Hope Street Teacher Voice Fellow. Email or Follow him @bryanchristo4.

Bryan Christopher teaches English and Journalism at Riverside High School in Durham, NC. He’s also an NCTE Policy Analyst and Hope Street Teacher Voice Fellow. Email or Follow him @bryanchristo4.