This post is written by members Richard Beach and Allen Webb. This is the first of two parts.

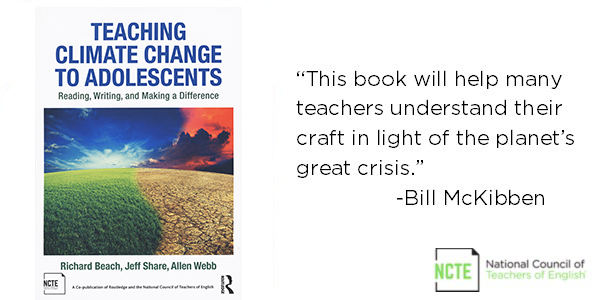

Even with the publication of our book, Teaching Climate Change to Adolescents: Reading, Writing, and Making a Difference (co-published by NCTE and Routledge), we are still asked: why address climate change in English language arts? Isn’t climate change a subject for Earth Science, not English?

Our response is multifaceted:

- We know global warming is happening and is caused by humans because of scientific findings.

- We know that climate change profoundly involves

- history, culture, society, and the social order;

- understanding the experience of others;

- reflecting on crucial moral and ethical questions;

- addressing inequality, racism, and nationalism;

- and using the imagination to better understand the past, present, and future.

- We believe that addressing climate change requires students to

- draw on the literary imagination,

- critically understand mass media,

- write creatively and persuasively, and

- develop an ability to speak out on perhaps the most profound challenge to face the human race and life on Earth.

- These areall practices found in the English language arts classroom.

After reading a chapter from Bill McKibben’s book Eaarth: Making Life on a Tough New Planet, one of Allen’s English students remarked this past week, “We are in serious trouble. It appears that global warming is much, much, much worse than I originally thought.” For most Americans, including most English teachers, the impact of climate change has not yet really sunk in. The corporate media is not informing us about the problem. Yet, what we do in the next few years will make the difference between the Earth warming 2ºC–the target set by the Paris Agreement—and 4ºC or more.

One of the world’s leading climate scientists has said that the difference between 2ºC and 4ºC is “human civilization.” In 2016 alone, the earth warmed 0.12ºC so that at that rate, two full degrees can happen in less than 20 years. Although the earth has only warmed 1ºC so far, climate change is already having profound impacts. Massive droughts around the world including in the US and Europe, heat waves, sea level rise, unprecedented human migration, devastating megastorms, and much more is already underway. 20 million people are currently in famine in Africa because of climate-change-related drought, leading to what the United Nations has described as, “the greatest humanitarian crisis since World War II.” Serious scientific predictions are that beyond 4ºC, dangerous climate feedback loops threaten the extinction of all life on Earth.

Science without the imagination fails to recognize these impacts of climate change on society, and what can be done to address it. In his endorsement of our book, leading climate-change expert, Bill McKibben (2010), notes the relevance of climate change to English language arts:

The scientists and engineers have done their work, providing a timely warning on climate change and producing the technologies like solar panels that would help take it on. It is the rest of us that have so far failed, and it’s largely a failure of . . . imagination, precisely the reason we have English class. This book will help many teachers understand their craft in light of the planet’s great crisis.

Responding to Literature

Even though the effects of climate change—rising temperatures, warming/acidification of oceans, sea rise/flooding, droughts, and extreme weather events—are increasingly evident, many people still do not understand the profound implications of climate change, nor do they perceive the need for immediate action. In responding to Romantic poetry and contemporary environmental writers as well as literary works often taught in the secondary curriculum—from The Grapes of Wrath to Lord of the Flies and from The Tempest to Frankenstein or Huck Finn—students are experiencing portrayals of the relationships between human beings and nature.

In reading more contemporary “cli-fi” literature, students are transported into the near and more distant future in which characters are coping with even more extreme adverse climate change effects. For example, in responding to Memory of Water (Itäranta, 2014), students enter into a world in which climate change has led to droughts and wars over water. They empathize with Noria Kaitio, the main character who is a seventeen-year-old living in a Scandinavian country. Noria has studied to become a tea master like her father, so she knows the location of hidden water sources. When her father dies, she acquires knowledge of a secret spring, but the army also learns that there is a spring and seeks to imprison her unless she reveals the location. Through the novel, students experience a future world coping with drought, a condition already impacting much of the Mideast, Africa, and India and forcing people to migrate to other parts of the world.

There are also many accessible, impactful works of climate fiction appropriate for secondary students, including three recent short story collections:

Martin, M. (Ed.) (2011). I’m with the bears: Short stories from a damaged planet. New York: Verso.

Milkoreit, M. (2016). Everything change:An anthology of climate change fiction. Tempe: Arizona State UP.

Woodbury, M. (Ed.) (2015). Winds of change: Stories about our climate. Coquitlam, Moon Willow Press.

Many of these stories have teenage protagonists or raise crucial questions that young people can further explore.

References

Itäranta, E. (2014). Memory of water: A novel. New York: Harper Voyager.

McKibben, Bill. (2011). Eaarth: Making life on a tough new planet. New York: St. Martins Press.

Richard Beach is Professor Emeritus of English Education, University of Minnesota. He is author/co-author of 25 books on teaching English, including Teaching Climate Change to Adolescents: Reading, Writing, and Making a Difference (Routledge) and co-distributed by NCTE, that includes a resource website. Twitter: #rbeach

Allen Webb is Professor of English Education and Postcolonial Studies at Western Michigan University, USA. He was a former high school teacher in Portland, Oregon. Allen has authored a dozen books, mostly about teaching literature for secondary teachers published by NCTE, Heinemann, and Routledge. He has also been studying, teaching, and involved in political organizing on climate change for the last five years. Currently, Allen teaches about climate change in literature, environmental studies, and English teaching methods classes.