This post is written by member Molly Ness.

Close your eyes for a second and think back to the last time you read aloud to a child; perhaps it was in your classroom of students or to a loved one, like your son or daughter or grandchild. In all likelihood, you did not merely plow through the book. Instead, you stopped periodically to get the reader’s insight. Perhaps you directed your class to make a prediction in a turn-and-talk. Or maybe you asked the child, “Why do you think the character felt that way?” But did you stop to think aloud? Did you use “I” language to model the thinking that you – as a proficient reader – did to comprehend the text?

All read-alouds – no matter the text genre, the age of the audience, or the content area – are an opportune time for students to internalize the metacognitive moves that a proficient reader employs to understand a text. In a think-aloud, a skilled reader provides quick explanations of what is going through his or her mind at periodic stopping points. With this transparent effort, students are more likely to internalize the reading comprehension strategies that will help them in their independent reading. Research shows the benefits of read-alouds. Students who are exposed to think-alouds outperform their peers who didn’t receive such instruction on measures of reading comprehension. The think-aloud is an energized, brief instructional burst that helps young readers take on the strategies modeled.

Despite their benefits, think-alouds are not commonplace in K–5 classrooms today. Because most teachers are proficient readers themselves, it may be difficult for us to pinpoint the sources of confusion for our students. In my work as a teacher educator, I have found that the explicit modeling component of think-alouds requires deliberate and diligent planning. Effective think-alouds do not emerge extemporaneously. We cannot assume that effective think-alouds will come to us naturally and without advance planning.

In a yearlong study with a teacher study group, I created a three-step process to help teachers think big with think-alouds. As I plan my think-alouds to be a powerful metcognitive strategy, I skim through the selected text three times – each rereading is described in the steps below. I equate this three-step planning process to teaching a child to ride a bike with training wheels. Just as training wheels provide stability and confidence in learning a new skill, so does the word-by-word script of a think-aloud. Our end goal is to be able to think aloud with comfort, ease, and skill, just as a young child hopes to ride a bike independently.

Read Once: Identifying Juicy Stopping Points

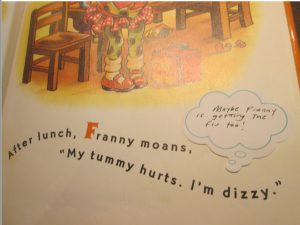

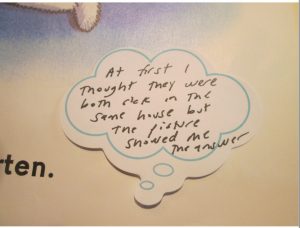

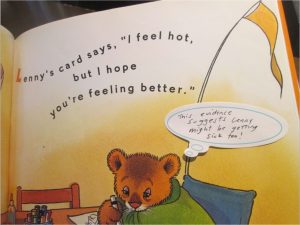

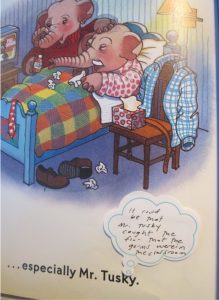

The first step in thinking aloud is a close examination of the text. I peruse the text searching for the comprehension opportunities in its pictures, words, and layout. I begin planning my think-alouds with a stack of sticky notes in hand. The purpose of this first reading is to mark the pages or paragraphs where I identify “juicy stopping points.” A juicy stopping point offers a range of possibilities, either comprehension opportunities or stumbling blocks. In my first reading, I may identify upwards of fifteen juicy stopping spots in a standard children’s picture book!

Read Twice: Determining Where and When to Think Aloud

In my second reading, I examine each stopping point and critically reflect on the need for that particular point. The goal here is to truly focus on which stopping points are appropriate and purposeful. I keep several factors in mind as I make my decisions, including my overall purpose for selecting this particular text, my learning objectives in this lesson, and which comprehension strategies are familiar or unfamiliar to my students prior to reading this text. After my second reading, I typically end up with about five to seven stopping points; these are the bare bones of the think-aloud to model in front of my students.

Read Three Times: Writing the Scripts on Sticky Notes

The goal of my third reading is to identify the script of exactly what I will say in front of students. I literally write out, in first-person narrative, what I will say in response to a text, so as to give students the chance to eavesdrop on our reading processes. Using “I” statements, I encourage my students to internalize these reading comprehension strategies so that they can emulate such purposeful reading.

The End Result of the Three-Step Process

Thinking aloud requires a paradigm shift in the language that we as teachers use during read-alouds. Typically, we ask our students surface-level questions such as “Where does the story take place?” and “Why do you think he left the town?” These questions serve merely to assess our students’ understanding of the text. Our time is better spent using language that builds their understanding, by showing them the thinking we are doing. As we think aloud, we mentor students in building the comprehension skills they need to become successful independent readers.

Molly Ness is an associate professor of education at Fordham University’s Graduate School of Education. She is the author of Think Big with Think Alouds (Corwin, 2018).