I went to see The Post the other day, and I confess that I cried when the Supreme Court ruled in favor of The Washington Post and The New York Times printing The Pentagon Papers, in favor of our First Amendment right of free press.

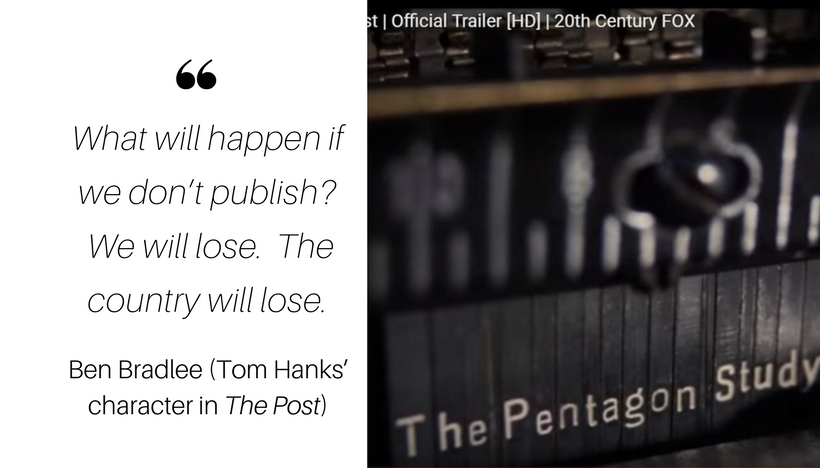

That right is so aptly spelled out in this scene from the movie:

“You’re talking about exposing years of government secrets,” Fritz Beebe (Tracy Letts’s character).

“Is that legal?” asks Michael (Will Denton’s character).

“What is it that you think we do here for a living,” replies Ben Bradlee (Tom Hanks’ character).

Your students, too, have a First Amendment right to report the truth even if that truth is unsavory, even if it exposes something that someone would rather not have exposed. This right was spelled out in the 1969 Tinker vs. Des Moines Community School District Supreme Court ruling which stated, “It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate.”

Unfortunately, the 1988 Hazelwood School District v. Kuhlmeier Supreme Court decision tightened control on student journalists when it found,

First Amendment rights of students in the public schools are not automatically coextensive with the rights of adults in other settings, and must be applied in light of the special characteristics of the school environment. A school need not tolerate student speech that is inconsistent with its basic educational mission, even though the government could not censor similar speech outside the school. Pp. 266-267.

The school newspaper here cannot be characterized as a forum for public expression…Accordingly, school officials were entitled to regulate the paper’s contents in any reasonable manner. Pp. 267-270.

The standard for determining when a school may punish student expression that happens to occur on school premises is not the standard for determining when a school may refuse to lend its name and resources to the dissemination of student expression. Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School Dist., 393 U.S. 503, distinguished. Educators do not offend the First Amendment by exercising editorial control over the style and content of student speech in school-sponsored expressive activities so long as their actions are reasonably related to legitimate pedagogical concerns. Pp. 270-273.

So now, because a state can loosen the ruling of the Supreme Court (but not tighten it), the New Voices campaign of the Student Press Law Center, the Journalism Education Association (an NCTE assembly), and other student journalism organizations is at work to get states to pass anti-censorship legislation that will grant extra protections for student journalists from administrative censorship, to loosen the laws on student publications and give student journalists their First Amendment rights. As of July 2017, twenty states do not have any extra protections for student journalists, twelve states have campaigns going to get New Voices legislation passed, six have protection for only high school students, and seven have protection for high school and college students. Check out the map to see where your state stands, to learn more about the campaign, and to download the Advocates Toolkit to help you organize a campaign in your state if your students are as yet unprotected. Why? Watch and listen.