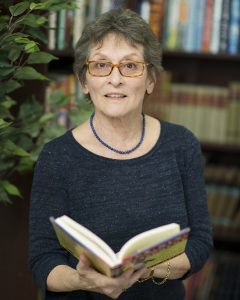

This post by Joan Bertin, former executive director of the National Coalition Against Censorship and 2017 NCTE Intellectual Freedom Award Winner, is reprinted from The Council Chronicle (June 2018)

Many people recognize that the First Amendment is essential to protect individual freedom, advance democratic ideals, advocate for social change, and hold elected officials accountable.

Fewer know about the critical role it plays in public education. It is the key to fending off attacks on public schools and teachers for teaching about evolution, climate science, and sexual health, and for exposing students to a wide variety of literature. These are the kinds of materials that are challenged in schools around the country on a daily basis.

The Role of Professional Educators

The Constitution doesn’t tell teachers or schools what or how to teach; rather, it recognizes the essential role of professional educators in selecting the materials for a sound educational program that serves the needs of all kinds of students.

However, the First Amendment does protect the right of students to read material that has been selected for its educational value, even if some people consider it offensive, controversial, or wrong-headed. The integrity of public education depends on this principle and the teachers who implement it. Without it, public education would be chaotic or meaningless.

Challenged Books

Consider a few of the books that have been regularly challenged: Beloved, Harry Potter books, Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret, and many more. (See lists of frequently challenged books compiled by the American Library Association.)

Textbooks are also vulnerable to challenge—especially history, social studies, science, and health texts—because some people disagree with content that is widely endorsed by subject matter experts.

Regardless of what kind of book is at issue, the test under the First Amendment is whether a book or idea has educational value, not whether people like it or agree with it.

This sounds reasonable in principle, but in practice it’s not always so easy. Faced with a specific book—say Adventures of Huckleberry Finn—some parents, students, and even teachers will be put off by language that is widely considered offensive. They’ll ask—why that book? Isn’t there another choice that’s not offensive? Of course there are always other books, but virtually every book is vulnerable to challenge. People have widely different views of what materials are “offensive” or “appropriate,” and it is not possible to please everyone; once one book is removed, there’s little rationale to prevent the removal of others. If today it’s Huck Finn, tomorrow it might be The Diary of Anne Frank or The Merchant of Venice.

The Remedy for “Bad” Speech

This doesn’t mean that teachers and students should ignore aspects of books that are disturbing or offensive. It’s often said that the remedy for bad speech is more speech, not enforced silence. The First Amendment encourages discussion of controversial ideas, in part to expose ideas that are flawed or harmful. In the marketplace of ideas, the theory is that better ideas will prevail through reasoned and informed debate and persuasion.

Preserving the freedom to read, think, and speak freely requires effort.

The challenge for teachers is to help students learn both to tolerate speech and ideas they dislike and to respond to those ideas critically and effectively. In other words, to prepare them to engage constructively in today’s diverse and contentious world.

I’m so grateful to all the members of NCTE who do this hard work on a daily basis. It’s not easy!

During her 20 years as executive director of the National Coalition Against Censorship, Joan Bertin tirelessly advocated on behalf of public school teachers facing censorship battles in communities throughout the United States. In 2017, NCTE honored Bertin with the NCTE National Intellectual Freedom Award for her courage in advancing the cause of intellectual freedom.