This post was written by NCTE member Ted Kesler, author of The Reader Response Notebook: Teaching towards Agency, Autonomy, and Accountability (2018, NCTE).

The reader response notebook (RRN) is a ubiquitous tool in schools. In at least grades two through eight, teachers rely on this notebook as evidence of students’ reading. In my extensive visits to schools around the country, I noticed a common application for this notebook: students write summaries of the books they read, or respond to a teacher prompt, such as “Describe the main character” or “Tell what new information you learned from this text,” and always “Be sure to provide text evidence.”

Ultimately, most responses by students are expository paragraphs or essays that are often solely directed to and read by the teacher for evaluation. Responses soon become monotonous, devoid of voice and intention.

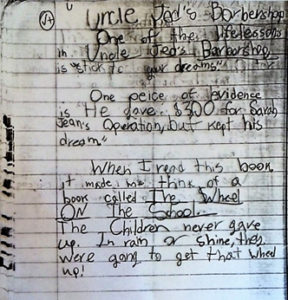

Here is an example from one of my third–grade students in my early years of classroom teaching:

The student met all the criteria for this response. She started with a topic sentence: a life lesson for the story, Uncle Jed’s Barbershop (Mitchell, 1998). She gave one piece of text evidence. She made a text-to-text connection to our read-aloud book, The Wheel on the School (DeJong, 1972).

Notice the √+ at top: that was my marking system to monitor my students’ responses. Fine. But expository responses often require substantial amounts of time, especially if they are done thoughtfully. We must consider the amount of time these kinds of written responses require and the fact that they inevitably take time away from students’ reading.

Moreover, notice that, like most responses of this kind, the student wrote a retrospective account (Hancock, 1993): in other words, students respond after reading the text. These kinds of responses then limit their opportunities to develop their thinking during reading, or what Hancock (1993) calls introspective journeys.

Finally, is this the only way to respond? What happens to students who are reluctant or resistant writers, or who do not represent their best thinking about the texts they read in writing?

In The Reader Response Notebook: Teaching towards Agency, Autonomy, and Accountability (2018, NCTE), I propose three key changes to the way we teach the use of the reader response notebook.

First, I encourage “designing on the page” that welcomes a wide array of writing and drawing resources. Second, I expand what counts as a text, including popular culture media. Third, I emphasize the sociocultural context of classroom literacy practices that supports students’ generative responses in their RRNs. My goal is to develop this ubiquitous tool for introspective journeys, where students can develop their thinking during reading.

Here are three examples from fifth-grade students of the generative thinking that is possible once we open up these new ways of using the RRN:

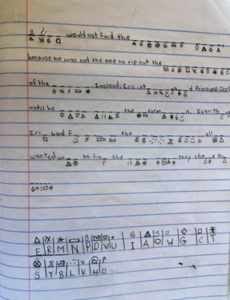

Figure 1. A coded message about Eric’s message in The Bully Book.

Figure 2. Text Messaging for All of the Above.

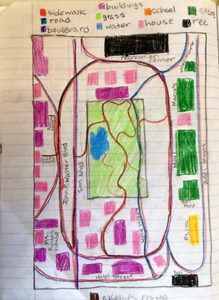

Figure 3. Skelly’s Route in The Graduation of Jake Moon.

In Figure 1, Samantha used a coded message to reveal the motives of the protagonist, Eric, in The Bully Book (Gale, 2013). In addition to showing impressive attention to detail, Samantha applied the same cryptic messages that Eric receives and uses throughout the book to solve the mystery of the Bully Book that torments his life.

In Figure 2, Emma imagined a text message exchange between Mr. Collins, the seventh-grade math teacher in All of the Above (Pearsall, 2008), with his adult daughter, at a pivotal moment in the story, right after the tetrahedron project with his afterschool math club was destroyed. In the book, we only know that Mr. Collins has an adult daughter and a son, but we know nothing of his relationship with them. Emma used a popular social media format to imagine this relationship.

In Figure 3, Elizabeth showed the route that Skelly, who has Alzheimer’s, took through the town on the night he wandered away from home unattended in The Graduation of Jake Moon (Park, 2002).

Elizabeth both envisioned the layout of the town and synthesized textual evidence to trace Skelly’s route. As in Figure 2, Elizabeth identified a pivotal moment in the story, and then realized that a map might be the best way to depict the tension and resolution of this event. She purposefully applied resources for map making, such as colors, shapes, symbols, and lines.

Ultimately, these new ways of using the RRN shape students’ identities towards becoming literate people. If we provide many opportunities for students’ risk-taking, approximations, and affiliation, and guide them to build bridges between school and their everyday literacy practices, they will strive towards proficiency. Their literacy development will become woven into who they are becoming in the world.

Ted Kesler is associate professor in the Elementary and Early Childhood Education Department of Queens College, CUNY, where he co-directs the MAT preservice program in elementary education. He does educational consulting in schools and school districts around the country.

Please visit him at www.tedsclassroom.com, @tedsclassroom, and www.facebook.com/tedsclassroom.