This post was written by NCTE members Rosanne Kurstedt and Jenny Tuten. It’s part of Build Your Stack,® an NCTE initiative focused exclusively on helping teachers build their book knowledge and their classroom libraries. Build Your Stack® provides a forum for contributors to share books from their classroom experience; inclusion in a blog post does not imply endorsement or promotion of specific books by NCTE.

“What’s in a name?” This famous quote from William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet resonates with us greatly, especially within the context of the diverse and multi-faceted school communities in which we work. Answered simply, we think there is a lot in a name. So much, in fact, that names warrant more attention in classrooms. Rudine Sims Bishop’s powerful and evocative metaphor of literature as windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors informs our thinking and practice.

Although teachers often use students’ names as an authentic way to introduce them to letters, sounds, and the way words work, we believe the study of names can have a broader and greater impact if we dig a bit deeper.

Think about it. The way each and every one one of us got our name has a story. And the story is part of who we are. Different cultures, religions, and even families have their own naming traditions. Learning the story of individual students’ names can be a powerful experience for students and their families; while, at the same time, creating a sense of community, respect, and understanding within a classroom.

The study of names can foster opportunities for students to

- learn about themselves (mirrors)

- connect and learn about and from each other (windows)

- learn about family cultures, traditions, and people they may have been named after, and

- connect with family members and help them connect with the classroom or school (sliding glass doors).

Jenny recently facilitated a family literacy engagement workshop at a local school in New York City. Fathers, mothers, uncles, sisters, and brothers joined their young learners in exploring the origin of their names. Tatiana learned that her mother loved all things Russian and chose her name to express that interest. Kaytish found out that her parents created her name as a compromise—a combination of a “K” name, for her dad Kevin, and Latisha, her mother’s name.

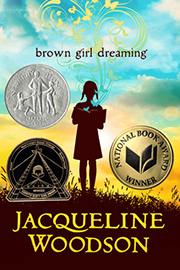

And after reading together an excerpt from Jacqueline Woodson’s Brown Girl Dreaming, about a girl named Jack, family members and children engaged in a rich discussion of names and gender. Some of the children laughed about the idea that a girl could be called Jack even as a nickname. Yet another student thoughtfully asked “Are there boy names and girl names?” We pondered this. A parent suggested some names that didn’t have clear gender markers, such as Taylor. We talked about why this was a good and hard question and the children and families determined they wanted to know more about traditions of naming.

In No More Culturally Irrelevant Teaching, Mariana Souto-Manning and teachers tapped into family literacies by engaging in an inquiry about students’ names. The project was called “No Name The Same.” Families were invited to share how each student received their name. The information was then made into a class book that lived in the class library. Copies were also made for all students and their families. The educators who implemented the No Name the Same project understood the power of learning about students’ names and bringing families’ voices into the classroom. The authors discuss how students felt proud as their family members’ voices were heard and celebrated.

The experiences highlighted above are just two ways to capitalize on the power of names. A great entry into such studies is reading various texts. Below we offer a list of books that focus on children’s names and identities. The first three are particularly useful for elementary-aged students.

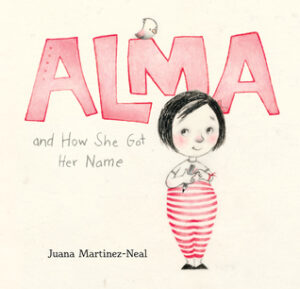

Alma and How She Got Her Name

Written and illustrated by Juana Martinez-Neal

What’s in a name? When Alma complains to her dad that her name is too long, their conversation helps her discover her family’s rich history and special strengths. We read this book with both teachers and children as an invitation to explore the meanings of our names.

My Name Is Sangoel

My Name Is Sangoel

by Karen Williams and Khadra Mohammed

Illustrated by Catherine Stock

Sangoel is a refugee from Sudan. His transition to the United States is challenging with so many differences from his homeland. And everyone mispronounces his name, which is a legacy of his father and grandfather. Sangoel’s creative solution is a great way to talk about problem solving and building relationships.

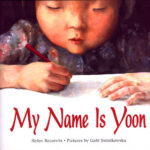

My Name Is Yoon

My Name Is Yoon

by Helen Recorvits

Illustrated by Gabi Swiatkowska

Why does my name look different? Why do I feel different? As Yoon, a recent immigrant, works through learning to write her name in English, we explore the conflicted and confusing emotions of young multilingual students.

Always Anjali

Always Anjali

by Sheetal Sheth

Illustrated by Jessica Blank

When Anjali can’t find a bicycle name plate with her name and other children start to tease her, she wants to change her name. Anjali learns to appreciate her name and be proud of it. Always Anjali, by Sheetal Sheth

Marisol McDonald Doesn’t Match/Marisol McDonald No Combina

by Monica Brown

Illustrated by Sara Palacios

Marisol McDonald learns to appreciate her name and how perfectly it fits with who she is.

Brown Girl Dreaming

by Jacqueline Woodson

An autobiographical chapter book written in free verse, with one chapter devoted to how Jacqueline Woodson got her name.

George

George

by Alex Gino

George is transgender and at ten years old, with the support of a best friend, she figures out how to be who she is in a world that sees her as a boy.

The books listed above are in no way an exhaustive list. We just wanted to provide you with a starting point. We’re disappointed we won’t be able to share more texts with you during an in-person Build Your Stack session this November, but hope to continue the conversation virtually!

Resources

Bishop, R. S. (1990). Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors. Perspectives, 6(3), ix-xi.

Souto-Manning, M., Llerena, C. L., Martell, J., Maguire, A. S., & Arce-Boardman, A. (2018). No more culturally irrelevant teaching. Heinemann.

Rosanne L. Kurstedt has been an educator for over 20 years. She is the associate director of READ East Harlem/Hunter College and is an adjunct professor at Hunter College where she teaches in the masters of literacy and doctoral programs. She is the author of several books and professional development guides for teachers, including Teaching Writing with Picture Books as Models and most recently a series titled 100+Growth Mindset Comments. She is a children’s book author and founder of The Author Experience, a nonprofit organization grounded in the transformative power of story, that partners with schools to build and sustain a culture of literacy—one in which students, families, and educators craft their stories and develop their voices together. Rosanne loves picture books and anything kid lit so she volunteers as the Assistant Regional Advisor for the New Jersey chapter of the Society of Children’s Books Writers and Illustrators.

Rosanne L. Kurstedt has been an educator for over 20 years. She is the associate director of READ East Harlem/Hunter College and is an adjunct professor at Hunter College where she teaches in the masters of literacy and doctoral programs. She is the author of several books and professional development guides for teachers, including Teaching Writing with Picture Books as Models and most recently a series titled 100+Growth Mindset Comments. She is a children’s book author and founder of The Author Experience, a nonprofit organization grounded in the transformative power of story, that partners with schools to build and sustain a culture of literacy—one in which students, families, and educators craft their stories and develop their voices together. Rosanne loves picture books and anything kid lit so she volunteers as the Assistant Regional Advisor for the New Jersey chapter of the Society of Children’s Books Writers and Illustrators.

Jenny Tuten is a professor of literacy education at Hunter College–the City University of New York. She is the director of READ East Harlem/Hunter College, a collaborative professional learning project uniting university faculty and K–2 teachers and school leaders to support teacher growth and student literacy learning. Her research focuses on the assessment and instruction of struggling readers and writers, the preparation of effective literacy teachers and coaches, and the development of responsive professional development models to improve literacy instruction in urban schools. She is the author of several books, including Crossing Literacy Bridges: Collaborating with Families of Struggling Readers.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.