This post was written by NCTE member Deborah Dean.

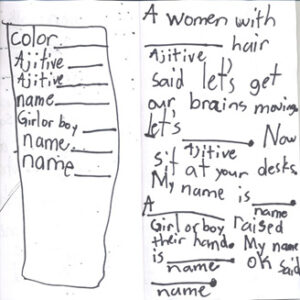

On the first day of a course for preservice teachers on teaching grammar in secondary schools, I ask students to share their feelings about grammar. Mostly, they express fear or dread in varying degrees of intensity. For many of them, grammar is something like what my granddaughter had in mind for the Mad Libs book she sent me, pictured here. (Mad Libs are stories with words removed and replaced by blank spaces.) It’s about parts of speech (which most of my students feel insecure about) or diagramming (which many of them don’t know how to do and think this class is going to be about), or esoteric terms like antecedents, objective complements, or copular verbs. No wonder they feel less enthusiastic in this course than, say, in the teaching reading course. Reading they know. Reading they like. Grammar? Not so much.

On the first day of a course for preservice teachers on teaching grammar in secondary schools, I ask students to share their feelings about grammar. Mostly, they express fear or dread in varying degrees of intensity. For many of them, grammar is something like what my granddaughter had in mind for the Mad Libs book she sent me, pictured here. (Mad Libs are stories with words removed and replaced by blank spaces.) It’s about parts of speech (which most of my students feel insecure about) or diagramming (which many of them don’t know how to do and think this class is going to be about), or esoteric terms like antecedents, objective complements, or copular verbs. No wonder they feel less enthusiastic in this course than, say, in the teaching reading course. Reading they know. Reading they like. Grammar? Not so much.

One of my goals for the course is to make sure that by the last day of it students feel confident, if not enthusiastic about the opportunity to infuse their future classes with language learning. On that first day, I stand in front of them with passion to explain that we are surrounded by language, by grammar. It is everything to us in our world. How can we NOT be engaged with it, not be passionate about helping students understand the value of realizing how knowing just a little about language can bring them confidence as they move through the world? People who understand language can make things happen. That is the point of grammar/language teaching. Not definitions. Not terminology. Language.

So how did we get here? To the point where future teachers are fearful of a course to help them teach language?

Mostly I think it’s because they have either not been taught anything at all about it or because they have been victims of poor understanding about what it means to teach grammar. When George Hillocks’s Research in Written Composition: New Directions for Teaching came out in 1986, explaining that research showed that grammar instruction did NOT improve writing, teachers tended to do one of two things: they stopped teaching anything about grammar at all or went “underground,” holding onto old grammar/diagramming books to secretly teach what they had learned and always taught.

Even decades later, remnants of these initial responses are still evident in DOL exercises or “grammar Mondays” where the lessons are all about correctness, about right and wrong. Nothing about passion. Nothing that might make language interesting to students. Or pertinent to their lives.

In the 90s, teachers like Constance Weaver tried to change the path of grammar teaching by promoting teaching “grammar in context,” something that research suggested should be more meaningful to students and more effective for their learning. The problem is that teaching grammar in context is tricky. It’s not really something that is easy to find in a book because contexts differ from one class to another. So, grammar in context requires a lot from teachers: time to develop unique lessons and some knowledge about grammar to know what and how to teach in the contexts of each classroom. For many teachers, the combination of these requirements was just too much. Again, grammar either went away or came from a workbook, reverting, again, to terms and correctness. Right and wrong. Too risky for many students. And many teachers are still in the same spot.

So how do we get to a better place, to a place where teachers and students see language infused in whatever they are teaching and learning, a place where language engages the interests of students to explore their lives and how language moves them through it? In little bits.

In my view, we don’t need to start with the big lessons on language; instead, we can start with the here-and-there lessons that enhance the texts we read and write. In two follow-up posts, I will go deeper into ways we get into language with reading and writing, but for now, let’s look at a few of the little-bit things a teacher can do to inspire interest in language.

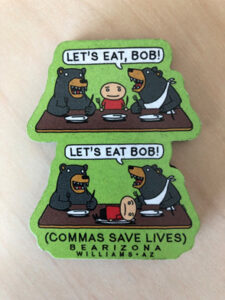

Bring in humor that depends on language for the humor. I see it in jokes or ads or memes, and will often share those with students. Mostly I just share the joke and we laugh. If a student doesn’t “get” it, she usually asks a neighbor to explain it—and how great is that? Students explaining language to other students! Here’s one I shared when a friend (who knows that I love language) sent me this magnet.

Bring in humor that depends on language for the humor. I see it in jokes or ads or memes, and will often share those with students. Mostly I just share the joke and we laugh. If a student doesn’t “get” it, she usually asks a neighbor to explain it—and how great is that? Students explaining language to other students! Here’s one I shared when a friend (who knows that I love language) sent me this magnet.- Richard Lederer’s website, Verbivore, shares all sorts of interesting things our language does: reverses natural order, for example. Why do we say we’re putting on our “shoes and socks” when we have to put on socks first? Language is full of interesting quirks, and having a few of them in our back pockets to share with students helps them see the interesting facets of the language they use, usually without thought, all the time.

If you have a few minutes at the end of class, consider showing some short videos that are funny about language. One sketch from Brian Regan is found at this QR code.

If you have a few minutes at the end of class, consider showing some short videos that are funny about language. One sketch from Brian Regan is found at this QR code.

Really, we just need to pump up our own interest in the language that swirls around us and bring it to our students for them to begin to see our interest in language. That, in itself, can often spark interest in students for the language that they see around them as they move through the world. And when we start with interest, we have a great foundation on which to build. What a wonderful way to start the lifelong journey of being language enthusiasts.

Deborah Dean, formerly a secondary English teacher, is a professor of English at Brigham Young University, where she teaches preservice and practicing teachers about writing instruction. She is the author of What Works in Grammar Instruction; Strategic Writing: The Writing Process and Beyond in the Secondary English Classroom; Genre Theory: Teaching, Writing, and Being; What Works in Writing Instruction: Research and Practices, and the Quick Reference Guide (QRG) Teaching Grammar in the Secondary Classroom.

Deborah Dean, formerly a secondary English teacher, is a professor of English at Brigham Young University, where she teaches preservice and practicing teachers about writing instruction. She is the author of What Works in Grammar Instruction; Strategic Writing: The Writing Process and Beyond in the Secondary English Classroom; Genre Theory: Teaching, Writing, and Being; What Works in Writing Instruction: Research and Practices, and the Quick Reference Guide (QRG) Teaching Grammar in the Secondary Classroom.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.