This post was written by NCTE member Gabrielle Stecher.

As we move into the back-to-school season, we are all inundated with ads for school-supply sales and the chaotic and often messy aftermath of store aisles strewn with notebooks, fuzzy pencil cases, and stacks of construction paper. As a university English teacher, I was never used to these sales being particularly relevant to the kind of work done in classrooms like mine. For the most part, the supplies we tell our students to bring to class centralize computer access and the readings we assign—the rest is often up to the discretion of the students and whatever note-taking methods they prefer. Suffice it to say, as a student I was used to an English classroom with little more than whatever book we were reading, a whiteboard, and sometimes a projector, and these experiences initially shaped what I thought my own classroom was supposed to look like.

That was until I started rethinking the kinds of active learning strategies that I was being told by my administration were necessary for increasing student engagement. There are so many wonderful resources for getting started with active learning, but I was looking for something more tangible than the usual think-pair-share and jigsaw strategies. As a crafter at heart, I wanted to physically make something that could, one, scratch that creative itch and, two, be reused semester after semester. Much of my experimentation with creating active learning materials involved my searching outside of the many wonderful pedagogical resources geared toward higher education instructors. For inspiration, I began following elementary school teachers on social media, and this has forever changed my outlook on how creative I can and should get with the activities I set up for my students. We need more K–16 partnerships across the board—that’s no secret (see, for instance, Jason Courtmanche’s MLA Profession essay on this topic here). But on a more individual level, one of the important things we can learn from our elementary teaching colleagues is how putting effort into crafting tangible and reusable active learning materials can transform any classroom for the better.

So, I purchased a cheap laminator that I saw teachers raving about to supplement the paper trimmer and stash of colored card stock and hook-and-loop fasteners I already had on hand and got to work. Every semester in my first-year writing courses, I spend a week working with my students on crafting stronger body paragraphs. We walk through all of the necessary components, from a topic sentence that functions as a mini-thesis statement to a concluding observation and transition and all of the evidence and analysis in between. It is one thing to model what these paragraphs can and should look like for your students and have them put into practice what they’ve learned in a first draft. But what I really wanted to figure out is how I could make negotiating the purpose of each sentence in a body paragraph an exciting group activity.

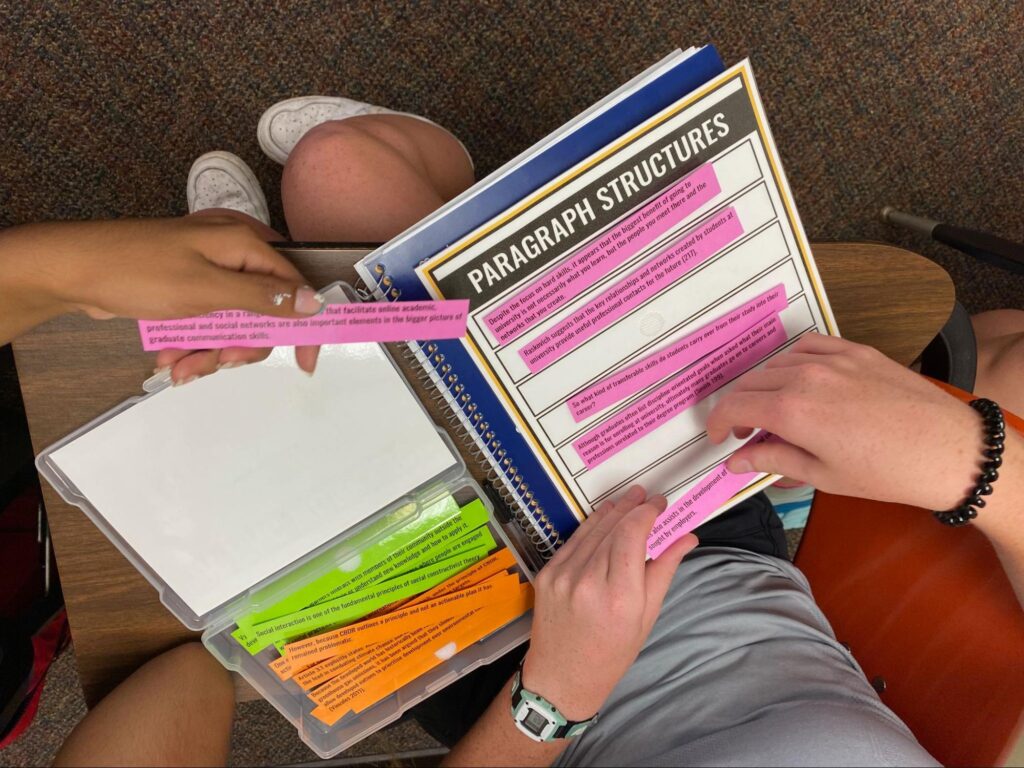

Taking what I’d observed about creating materials for centers-style instruction in early elementary classrooms, I developed the following activity to help my students better visualize the components of a successful body paragraph. It has since become one of my greatest hits and an activity that has come up again and again in student conferences and in my course evaluations because it is that engaging and evokes nostalgia about the kinds of active learning activities students got used to as children. Here, students work in small groups to reconstruct paragraphs from scrambled-up sentences; they must debate and determine the function and original placement of each sentence. As they work, they can attach and remove the laminated sentence strips on the corresponding board. Together, we discuss our findings, comparing our arrangements with what the writer actually wrote. If a group proposes a different order for the sentences than the author intended, we work together to rationalize the new arrangement and offer suggestions for how the author of the paragraph could revise it. Ultimately, students leave with the ability to better visualize the different ways paragraphs can be organized, as well as a greater understanding of how they must keep their readers’ needs in mind as they structure and revise their own body paragraphs.

So, as these back-to-school sales turn to clearance deals, think about how you might stock up on some supplies that can transform your own pedagogy. Get crafty, look outside of your grade level and subject for inspiration, and, most importantly, when you create something that works, share what you’ve learned with the colleagues in your department! If we want to create lasting, collaborative partnerships that can truly transform the ways we engage students, we have to be willing to get creative and share what works so that we can continue to learn from one another.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.

Gabrielle Stecher is a lecturer and assistant director of undergraduate teaching in the English department at Indiana University Bloomington.