This blog post was written by NCTE member Chyann Hector. It is part of Build Your Stack®, an NCTE initiative focused exclusively on helping teachers build their book knowledge and their classroom libraries. Build Your Stack provides a forum for contributors to share books from their classroom experience; inclusion in a blog post does not imply endorsement or promotion of specific books by NCTE.

“My history begins before me. It begins before the stories I know and the ones I long to know. My history begins hundreds and hundreds of years ago . . . and so does yours.”–This Book is Anti-Racist, Tiffany Jewell (2020).

Who is the greatest storyteller you know? Maybe it is a published author or someone you know personally. For me, it’s my grandmother. Over the years, she has recounted dozens of elaborate stories detailing her rich and varied life experiences. Some are etched into my brain because of the many times she’s told the same tale.

Oral storytelling is innate to hundreds of cultures but is often decentered in many traditional educational spaces. Our Common Core State Standards map out how we should teach and have students learn to write a narrative. There must be a sequence of events, and techniques like figurative language, characterization, a beginning, middle, and end. What room does this leave for us to explore the stories that raised us? What room does this leave for communal scribing?

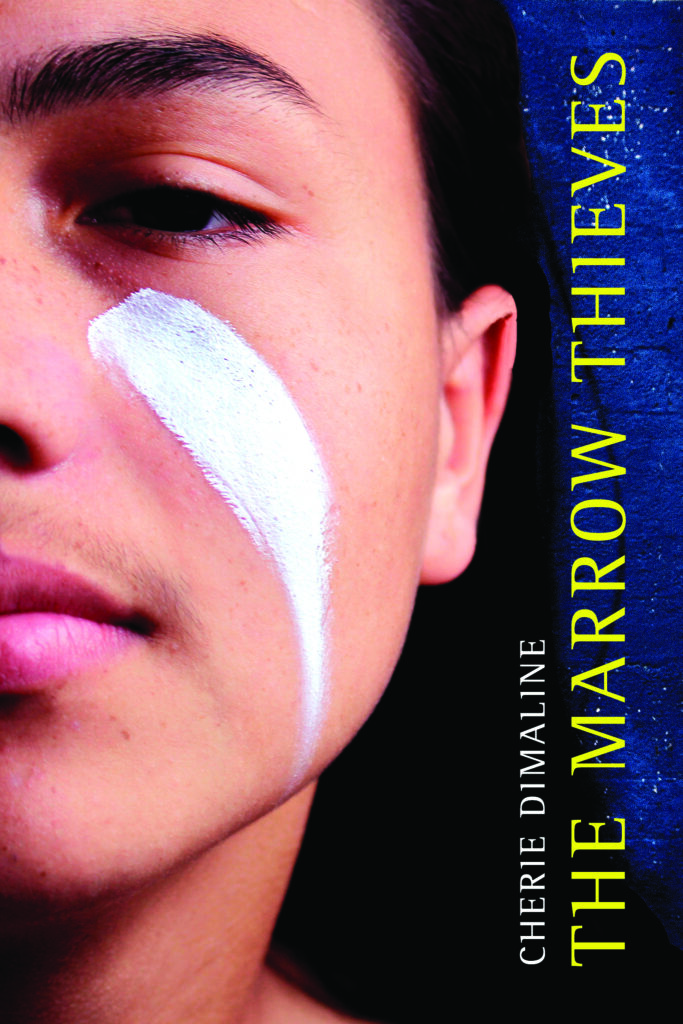

These questions lead me to Cherie Dimaline’s The Marrow Thieves as a textual anchor for a tenth-grade world literature unit. At the heart of this novel is the power of language, stories, community, and intergenerational solidarity. Dimaline reclaims the practice of storytelling through two unique structures that interrupt the present plot: “Story” and “coming-to-stories.” The former is a collective history (real and fictionalized) of the Anishinaabe people. The latter details the individual history of a character that is shared with the group. Both stories are shared orally among the teen and adult characters as a form of education and bonding. There is no novel without the characters reaching back into the past to understand their present.

With “coming-to-stories” as a model, I challenged myself and my students to record the oral history of a beloved community member and morph the recorded interviews into creative narratives. Another centerpiece of Cherie Dimaline’s novel is the importance and validity of the “found family.” So, it was important to make the distinction that students could interview any community member about a pivotal moment in their lives. They chose to interview parental figures, siblings, cousins, friends, coworkers, and even other teachers. The intention was to position students and their community members as experts of memory, experience, and knowledge and to interrogate how hi(stories) influence personhood.

To begin, I adapted the Smithsonian Archives Institute’s “Oral History Guide” into mini-lessons and gave students a planning guide for brainstorming and note-taking. We discussed what it meant to respectfully care and craft someone else’s story. There were mini-lessons on perspective, point-of-view, and the nested/frame story structure before interviews.

In The Marrow Thieves, Frenchie, the protagonist, yearns to learn his native tongue and feels disconnected from his culture altogether. Dimaline positions language as directly linked to identity and memory. Using this as a model, we talked about the power of multilingualism and techniques to make a place for it in writing, whether that meant providing direct, conversational, or implicit translations, or employing the curtain (Reese 2016). This allowed bilingual students to preserve and make space for varied cultural discourse within the classroom.

With the voices of their loved ones, students found a new way to give writing meaning. Some stories have yet to be told and never make it into a classroom. My hope is for this project to disrupt that. To say that every story rooted in pain and joy and every feeling in between deserves reverence. With Cherie Dimaline as a guide and oral storytelling as a tool, students become scribes of their own history.

Reference

“‘We Are Still Here’: An Interview with Debbie Reese.” 2016. English Journal 106, no. 1 (September): 51–54. https://doi.org/10.58680/ej201628735.

Chyann Hector (she/her) is an educator and poet-writer based in Georgia. She is passionate about centering equity and justice in literacy education. Her writing explores the experiences of Black women who are immigrants and descendants of immigrants. She has worked in the secondary English space for five years and now seeks ways to be a part of transforming education beyond the classroom.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.