By: Dr. Ted Kesler, coeditor, Talking Points

Modified from a speech that Dr. Kesler gave as chairperson at a May 2025 graduation ceremony for undergraduate and graduate students in the Elementary and Early Childhood Education Department in the School of Education at Queens College, CUNY

Dear Graduates,

As you enter this noble profession, I want you to know that you will always have children with difficult lives. In our troubled world, you will have children who may have experienced linguistic differences, acts of prejudice, housing or food insecurities, troubled home lives, fractured families, wars, disease, and death. You may have children terrified they won’t see one of their parents ever again when they return home from school. I want to challenge you to consider what kind of teachers you will be for those children.

In 1990’s The Boy Who Would Be a Helicopter, Vivian Gussin Paley, the MacArthur “genius” early childhood educator, stated, “Aside from all else we try to accomplish, we have an awesome responsibility. We must become aware of the essential loneliness of each child,” whatever the source. “Our classrooms, at all levels, must look more like happy families and secure homes, the kind in which all family members can tell their private stories, knowing they will be listened to with affection and respect.”

In 2019’s The Vulnerable Heart of Literacy, educator Elizabeth Dutro teaches us that this deep listening requires two actions: testimony and critical witness. Testimonio is an important form of storytelling with roots in Latin American indigenous communities. Testimonio is a story of personal experience that signals the larger histories of oppression or struggle to which it is connected. It is one form of autoethnography, in which we discover the grand narratives that shape us. Autoethnographies are connected to our cultures, histories, experiences with loved ones, and the pain, struggles, joy, and celebrations that represent us. Testimony is an intentional move toward vulnerability in your teaching. Testimony is also your source of strength for the kind of teacher you intend to be.

I am the youngest of four siblings. My parents were Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe who survived the horrors of World War II. They came to the United States in their early twenties with no money and no English. My father also had no family or friends in the United States. They met at a foreign students’ event in Cambridge, MA. My father was attending MIT. My mother was in the second class at Harvard Medical School to admit women.

The ravages of war and the horrors of anti-Semitism shaped my testimony. Even as a young child, I was aware of my mother’s fractured family, of my father’s deep emotional pain that he survived the war while his parents didn’t. I was also shaped by the enormous value my parents put on education for a better life, for a life of possibility.

But by the time I came around, I was also nurtured and deeply loved by my three older siblings. My parents were becoming secure in their professions. We were living the American Dream.

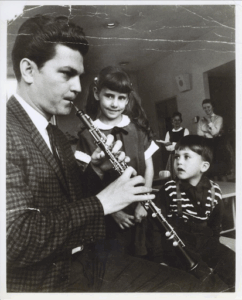

Here I am at five years old, in kindergarten. This picture was featured on the front page of our county newspaper. It was the first time I ever heard a wind ensemble. I was mesmerized by the oboe player. My kindergarten teacher, Mrs. Crossen, (the taller woman next to the principal), must have noticed because she arranged for a second-grade girl and me to meet the oboe player after the performance. Soon afterward, my parents got me started on the violin, which I play to this day.

Here I am at five years old, in kindergarten. This picture was featured on the front page of our county newspaper. It was the first time I ever heard a wind ensemble. I was mesmerized by the oboe player. My kindergarten teacher, Mrs. Crossen, (the taller woman next to the principal), must have noticed because she arranged for a second-grade girl and me to meet the oboe player after the performance. Soon afterward, my parents got me started on the violin, which I play to this day.

It was also soon afterward that my world unraveled. My mother became sick. For five years she was wracked with pain and disease. She had long stretches in the hospital. Children were not allowed to visit then, and I would not see her for weeks. I missed her terribly. When he wasn’t working, my father spent all his time in the hospital. We became bankrupt, broke. We kids were left to fend for ourselves. School became a disconnected, distant place. I was full of anguish.

After my mom died, I suppose in a gesture of kindness the school named the library in her honor. One day, I went in there with a troublemaker classmate, and at my urging, we ransacked the library. We knocked most of the books off the shelves. The school administrators never found out who did it. To this day, I think about why I did that. I suppose it was from a deep rage at my mother’s anguish, at not being able to save her, that the larger world kept spinning while my world unraveled, that there was no one to be a witness to my testimony, and so I felt like the loneliest boy in the world.

Now I’m not saying that, as a classroom teacher, I readily share these stories with children. These are moments of my testimony, my autoethnography, that give my foundation for why I teach. They enable me to make connection. I want to be someone who can bear witness for boys like me.

So let’s turn our attention to the second way to support children: critical witness. Critical witness is deep listening, a radical empathy. In Cori Doerrfeld’s 2018 picturebook, The Rabbit Listened, Tyler’s magnificent block structure comes crashing down. Animal after animal—the chicken, the bear, the elephant, the hyena, the ostrich, the kangaroo, the snake—offers advice, and leaves. Only the rabbit approaches Tyler quietly, stays, and listens until Tyler feels safe enough to express his hurt, his frustration, his anger, his relief, until he is finally ready to rebuild with the conviction, “It’s going to be amazing.”

My call to all of you is to know your own testimonials, your own autoethnography. Be brave by embracing these vulnerabilities, so your students feel safe sharing their testimonios. Then, be the rabbit: provide critical witness for your students. As Dutro concludes: By doing this, our classrooms become places “of connection, of love, and of respect for the knowledge that comes from pain, from struggle, and toward the power of bringing that knowledge to learning.”

Ted Kesler, EdD, is chairperson of the Elementary and Early Childhood Education Department in the School of Education at Queens College, CUNY. He is coeditor, with Dr. Marcela Ossa Parra, of the NCTE journal Talking Points. www.tedsclassroom.com

Ted Kesler, EdD, is chairperson of the Elementary and Early Childhood Education Department in the School of Education at Queens College, CUNY. He is coeditor, with Dr. Marcela Ossa Parra, of the NCTE journal Talking Points. www.tedsclassroom.com

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.