By: Patty McGee, NCTE member and literacy consultant, author, and educator

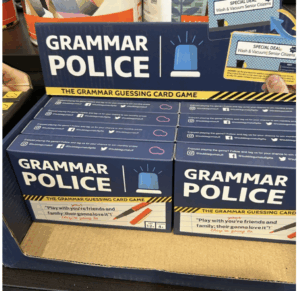

“Grammar police.”

“Edit or regret it.”

“I am silently correcting your grammar.”

“Fatal flaws.”

“Grammar warden.”

These phrases dominate many classroom conversations about grammar, creating a system of intimidation and judgment in language instruction. This punitive rhetoric creates exactly what it claims to prevent: fear, shame, embarrassment, and avoidance of writing.

The Lasting Effects of Grammar Shame

One story remains seared in my memory. A friend shared how, as a young student—likely with undiagnosed dyslexia—she had written her first full-page piece. Proud of this milestone, she eagerly awaited her teacher’s response, expecting praise or at least acknowledgment of her achievement.

Instead, the teacher held up my friend’s paper and used it as an example of poor grammar for the entire class. Worse still, the teacher posted the paper in the hallway, covered in red corrections, as a public display of what not to do.

I know too many stories that resemble this one.

This “gotcha” mentality and accompanying shame have embittered grammar instruction for generations. You’ve seen it or experienced it: students hunching over grammar worksheets, tensing up when called on to identify a subordinate clause, feeling the sting when their answer is incorrect. Usually, one student in the class becomes the budding grammarian who shares the correct answer every. Single. Time.

This experience creates a system of grammar haves and have-nots, separating the grammatically elite from the linguistically challenged.

The damage extends far beyond the classroom. This pervasive punitive approach creates adults who freeze when writing emails, second-guess every sentence, and hold the belief that they are terrible writers.

The Root of the Problem

Traditional grammar instruction, with its emphasis on rote memorization and decontextualized drill, is the root of the problem. Consider the common practice of teaching grammar in isolation from actual writing. It’s like teaching someone to use a paintbrush by having them memorize the names of different brush types without ever letting them touch paint to paper.

Grammar is to writing as a paintbrush is to an artist—it’s a tool for creating something beautiful and meaningful. When we separate grammar from its purpose, we drain it of its power and relevance.

A Better Way: Grammar Study

Instead of the gotcha approach, we need what my coauthor Tim Donahue and I call “Grammar Study.” This approach treats grammar as a set of flexible tools for achieving specific effects in writing while providing multiple opportunities to build grammar knowledge. Grammar Study allows students to get curious, hypothesize, play, seek feedback, and reflect—creating multiple entry points for studying and learning grammar.

An Example: Teaching Complex Sentences

Let’s say you’re teaching students how to create complex sentences.

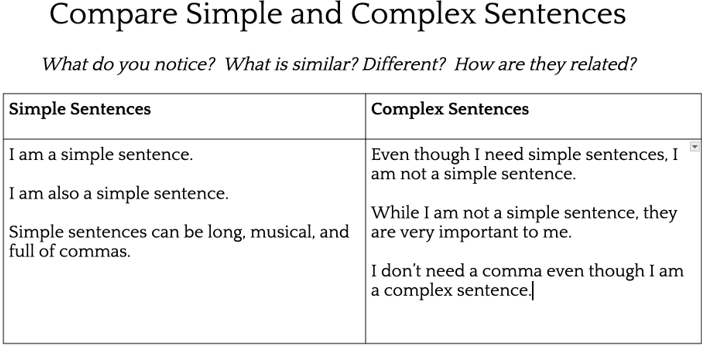

Step 1: Begin with Curiosity. Share a set of simple and complex sentences, and ask duos of students to theorize the difference between them. Some theories may be off base, but this isn’t a time for mastery—it’s the first step in setting Grammar Study in motion.

(McGee & Donohue, p.75)

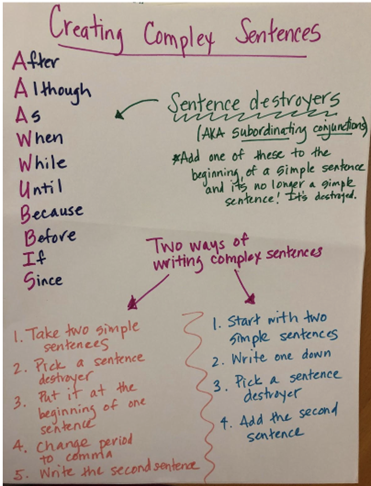

Step 2: Explicit Instruction. Following this exploration, provide an explicit lesson on combining simple sentences into complex sentences. It can be helpful to use an anchor chart showing how to use “sentence destroyers” (subordinating conjunctions) to build complex sentences.

(McGee & Donohue, p. 77)

Step 3: Experiment and Play. Give students a chance to experiment with their budding knowledge using grammar manipulatives—tangible items that partners can move around to try out grammar concepts.

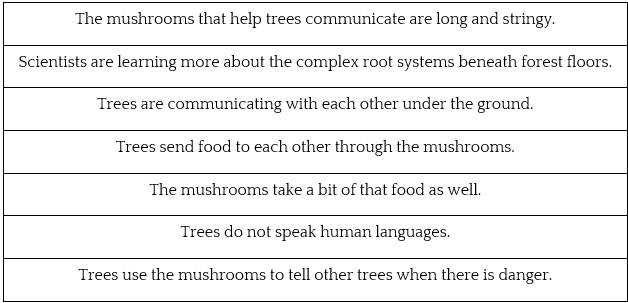

Ask students to cut out the sentences and use the anchor chart to create complex sentences. For example: “Although trees do not speak human languages, trees are communicating with each other under the ground.”

If students are inaccurate, instead of correcting them, nudge with words like, “That is almost a complex sentence. You’re missing one thing. See if you can find it.”

Shifting the Culture

These three connected but different experiences eliminate the shame, embarrassment, and punitive tone of traditional grammar instruction.

Let’s shift the culture around grammar from one of judgment to one of artisanship. In this new approach:

- Errors become experiments.

- Mistakes become learning opportunities.

- Revision becomes a celebration of growing skill.

Students learn that even professional writers struggle with grammar, that language is inherently messy and beautiful, and that the goal isn’t perfection but effective communication.

When we approach grammar instruction this way, we honor both the complexity of language and the humanity of our students. We create writers who see grammar not as a weapon of judgment, but as a powerful tool for expressing their ideas with clarity and style.

Patty McGee is a literacy consultant, author, educator, and advocate for delightful literacy practices, as well as a member of NCTE. Her recent publication with Tim Donohue is Not Your Granny’s Grammar: An Innovative Approach to Meaningful and Engaging Grammar Instruction. www.pattymcgee.org

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.