This post was written by NCTE member Lorena Germán.

Our Racialized Imaginations

In The Dark Fantastic, Ebony Elizabeth Thomas talks about the idea of the racialized imagination gap. She explains that due in part to a lack of diversity in media (books included), there exists a gap, a missing piece in our national imagination in terms of race. This is to say that as individuals that make up this nation, we have a space in our imagination tainted by the monster of racism and bias. And she’s not wrong.

What happens to BIPoC when the majority of the books they read exclude them? And what happens when the books that include them present them as evil, monstrous, and/or suffering, broken? We would be naive to think this doesn’t shape and mold our perception of these groups of people. This racialized imagination gap explains how a teacher might see a toddler and think that exclusion is appropriate. It explains how someone might think “danger” and tighten their grip on their belongings when they see a dark-skinned person walking by. It explains how children may not want to play with another child based on their appearance. It explains how a police officer might see a Black person and think that shooting is the answer.

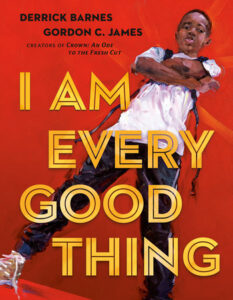

So what Derrick Barnes and Gordon C. James have done in their new book I Am Every Good Thing is deeply meaningful and important. This children’s book is an example of the way literature speaks to a social problem, addresses stereotypes, creates a counternarrative, and moves us toward restoration. It is an antiracist text.

In this beautifully illustrated and powerfully poetic book, Barnes and James move us to appreciate Black boys in all their ordinariness, marvelousness, beauty, and thunder. They invite us to see them as children, as whole, as regular people—as we should see them. The lines offer us a counternarrative to the stereotypes that exist of Black men and boys as violent and aggressive—negative portrayals that affect the public’s understanding and attitudes.

In this beautifully illustrated and powerfully poetic book, Barnes and James move us to appreciate Black boys in all their ordinariness, marvelousness, beauty, and thunder. They invite us to see them as children, as whole, as regular people—as we should see them. The lines offer us a counternarrative to the stereotypes that exist of Black men and boys as violent and aggressive—negative portrayals that affect the public’s understanding and attitudes.

This counternarrative, Barnes has explained in various interviews, was intentional. He wanted to strategically address our national perception and beliefs about Black boys and offer us an alternate viewing, and more important, to offer affirmation for this generally misrepresented and underrepresented group. He simultaneously talks to us, addresses our racial imagination gap, and speaks to the heart and soul of Black boys. In so many words, he says, “I see you. I love you. I value you. You are wonderful.”

This Book in Our Classrooms

Bringing this message and imagery into our classrooms is imperative. There are several ways to do it, depending on the age of your student group. For a younger age group, simply incorporating the book as a core text, reading it aloud, and celebrating the book works. If you can, also find ways to display copies of the book in your classroom. These images of Black boys are artwork; they are beautiful. Do this with students regardless of their ethnic identity. We all have a racialized imagination gap and we need to unlearn these ideas. We all need to see these images and witness Black boys experiencing joy. This book is for all classrooms and for all students.

If you teach an older age group, I would explicitly discuss the stereotypes imposed on and believed about Black boys. I would start there, introduce this book, among other materials, and discuss the ways the book is working against that stereotype, therefore functioning as a counternarrative. I’d pair the book with excerpts, other books, music, and even film clips. Create a collection of counternarrative tools and offer students the truth that counters the lies and stereotypes. English classrooms need to do better at prioritizing and teaching truth in explicit ways.

This is how we do antiracist work in the English classroom. We take on real-life problems and find ways to create real-life solutions through education and through literature. It’s the role we can play in moving our society toward positive social transformation (see Culturally Sustaining Pedagogies: Teaching and Learning for Justice in a Changing World, edited by Django Paris and H. Samy Alim).

Lorena Germán teaches at Headwaters School in Austin, Texas. She is chair of the NCTE Committee Against Racism and Bias in the Teaching of English and is a cofounder of the Multicultural Classroom and of #DisruptTexts.

If you missed the lively NCTE online event featuring Derrick Barnes and Gordon C. James, with Kimberly N. Parker as moderator, you can access that here.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.