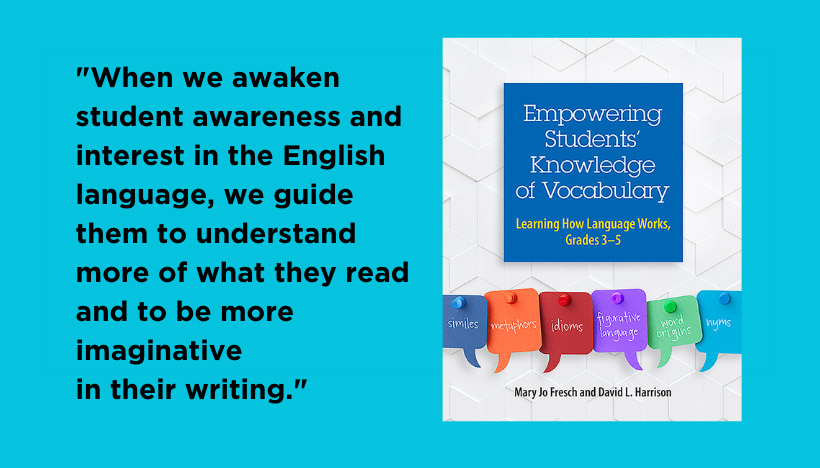

This post was written by NCTE members Mary Jo Fresch and David Harrison, authors of Empowering Students’ Knowledge of Vocabulary: Learning How Language Works, Grades 3-5.

From the teacher’s perspective (Mary Jo)

How can we support student development of word knowledge by exploring vocabulary in new ways? We know depth of vocabulary assists in reading and writing. Graves (2006) analyzed a large number of vocabulary learning research studies. He found that the difference between linguistically advantaged and disadvantaged students’ vocabularies can be as high as 50 percent. A novel look at specific word categories will add an engaging way for students to learn more words without relying on the memorization model.

In Empowering Students’ Knowledge of Vocabulary (Fresch & Harrison, 2020), we dive into six categories of words. An examination of the “nyms” (acronyms, antonyms, eponyms, homonyms, retronyms, synonyms); similes, metaphors, idioms, shades of meaning and word origins all take students into an interesting realm of understanding the English language.

Our aim is to make words memorable, instead of memorized. We know joyful engagement can entice even the most reluctant learners (Fresch, 2014), so finding ways to motivate all students is crucial. As well, sharing examples of an author’s work can bring a ring of authenticity to the lessons we plan.

We believe a two phase approach for sparking student interest in words makes their work more engaging. What better way to entice student to think about their word choices than to examine the work of an author? In each of the categories, David L. Harrison shares his approach to writing. Mentor texts show students how this looks and sounds. Students are then scaffolded across several lessons to incorporate the ideas into their own writing. For example, when examining shades of meaning, David shares a story he wrote about a witch.

From the writer’s perspective (David)

Kids tend to write in short statements, unadorned with nyms, metaphors, and other elements of language that can make writing so entertaining. I started with a similar offering, a shaved-down version of the opening lines from a story called “Sally,” published in The Witch Book (Rand McNally, 1976.) Then I showed by example how to add the magic of language put to good use. Here’s what I gave them.

- A witch is flying through a terrible storm.

- It is nighttime.

- She isn’t afraid.

- She is laughing.

Not very exciting, I pointed out. What does it need? More description? More action? Better vocabulary? What kind of clouds? Is there any lightning? What does it look like when a witch flies through a nighttime storm? Is it noisy up there? What about thunder? How do we know the witch is having fun? Can we hear her laughing? Does the witch have a name? The opening lines became:

Huge storm clouds filled the sky. When lightning flashed you could see a witch flying among the clouds. You could hear her laughing above the sound of thunder. Far below everything was quiet. But up high the storm was howling. It was a good night for Sally the witch to go flying. She felt reckless. She yelled happily as she flew.

The writing continues to improve as students discover how to add metaphors, similes, and synonyms to season the delicious scene building above our heads.

Clouds become volcanoes erupting in the night. A blue-white tongue of lightning crackles across the sky. Cackling merrily, a darting form swoops and glides like a bony, black bird. Shrill laughter rings out above rumbling thunder.

From the teacher’s perspective (Mary Jo)

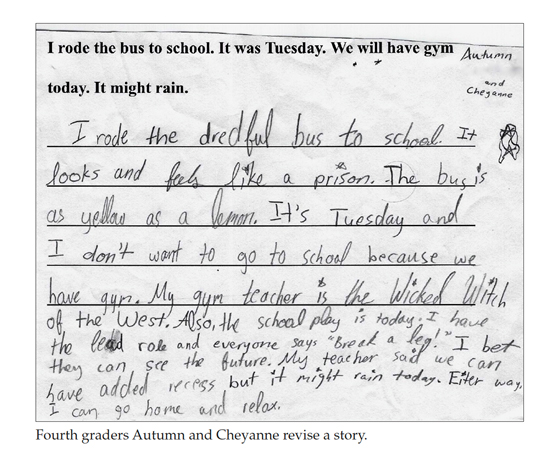

The teacher then takes the idea of shades of meaning and provides the students with a prompt. Below is a sample of student work, inspired by David’s suggestions:

Not only do we use David’s writing as mentor texts to inspire better vocabulary, but we also asked a number of well-known children’s authors to share about their experiences and ideas about word choice.

From the writer’s perspective (David)

Mary Jo and I wanted to share input by some of America’s best, and best known, authors of books for young people. Chapter 6 features a who’s-who list of eight writers whose collective work reach and thrill young fans around the globe. They are Larry Dane Brimner, Margaretta Engle, Charles Ghigna, Nikki Grimes, Kenn Nesbitt, Obert Skye, Janet Wong, and Jane Yolen. What they have to tell us about how they make stories and poems that fascinate millions of readers adds extremely helpful insight to our book. Here are three snippets.

Nikki Grimes says her challenge is, “to tell my story, paint a mental picture, using as few words as possible…With so little space, I must choose my words with precision because every word counts.”

Kenn Nesbitt says, “When poets write, they often think of many ways to write each line. Even after they choose the words they feel best express what they are trying to say, they may go back and rewrite, change a word here, a phrase there, until they can find no way to improve what they have written.”

Jane Yolen provides a concrete example of what Nikki and Kenn mean by telling about a night she was trying to describe the moon in a story she was writing and none of the usual adjectives, similes, or metaphors seemed quite right. Finally, Jane went for a walk, looking up at the moon and listening to night sounds as her feet crunched through the snow. Jane goes on to explain how she eventually combined two words—ballooning and hullabaloo—in the perfect one word: hulaballooning.

Mary Jo and I are truly delighted to bring such wisdom from major writers directly into the classroom.

From the teacher’s perspective (Mary Jo)

When we awaken student awareness and interest in the English language, we guide them to understand more of what they read and to be more imaginative in their writing. Fun with these categories (P.S.—your homework is to look up “retronyms”—students love this category!) encourages students to do their own, self-selected research into words. And what better way to empower students than to make them independent?

Mary Jo Fresch is an academy professor and professor emerita in the School of Teaching and Learning, College of Education and Human Ecology, at The Ohio State University. She has been an educator for more than forty years. Her research focuses on the developmental aspect of literacy learning. She has over sixty peer-reviewed articles in professional journals; her professional books include Strategies for Effective Balanced Literacy (2016), The Power of Picture Books: Using Content Area Literature in Middle School (2009), Engaging Minds in English Language Arts Classrooms: The Surprising Power of Joy (2014), and An Essential History of Current Reading Practices (editor; 2008). She coauthored Learning through Poetry (2013), a five-book phonemic and phonological awareness series, and 7 Keys to Research for Writing Success (2018) with David L. Harrison. Fresch continues to provide professional learning workshops for teachers across the United States.

Mary Jo Fresch is an academy professor and professor emerita in the School of Teaching and Learning, College of Education and Human Ecology, at The Ohio State University. She has been an educator for more than forty years. Her research focuses on the developmental aspect of literacy learning. She has over sixty peer-reviewed articles in professional journals; her professional books include Strategies for Effective Balanced Literacy (2016), The Power of Picture Books: Using Content Area Literature in Middle School (2009), Engaging Minds in English Language Arts Classrooms: The Surprising Power of Joy (2014), and An Essential History of Current Reading Practices (editor; 2008). She coauthored Learning through Poetry (2013), a five-book phonemic and phonological awareness series, and 7 Keys to Research for Writing Success (2018) with David L. Harrison. Fresch continues to provide professional learning workshops for teachers across the United States.

David L. Harrison has published more than 100 books of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction for young readers and teachers, and has been anthologized in 185 others. Harrison’s professional books include Easy Poetry Lessons That Dazzle and Delight (1999), with Bernice Cullinan; “Yes, Poetry Can,” the poetry chapter for Children’s Literature in the Reading Program (edited by Deborah Wooten, Lauren Almonette Liang, and Bernice Cullinan, third [2009], fourth [2015], and fifth [2018] editions); Learning through Poetry (2013), with Mary Jo Fresch, a five-volume set to build phonemic awareness and phonics skills; and Partner Poems for Building Fluency: 40 Engaging Poems for Two Voices with Motivating Activities That Help Students Improve Their Fluency and Comprehension (2009), with Tim Rasinski and Gay Fawcett. In 2020 he became the first recipient of the Laura Ingalls Wilder Children’s Literature Medal.

David L. Harrison has published more than 100 books of poetry, fiction, and nonfiction for young readers and teachers, and has been anthologized in 185 others. Harrison’s professional books include Easy Poetry Lessons That Dazzle and Delight (1999), with Bernice Cullinan; “Yes, Poetry Can,” the poetry chapter for Children’s Literature in the Reading Program (edited by Deborah Wooten, Lauren Almonette Liang, and Bernice Cullinan, third [2009], fourth [2015], and fifth [2018] editions); Learning through Poetry (2013), with Mary Jo Fresch, a five-volume set to build phonemic awareness and phonics skills; and Partner Poems for Building Fluency: 40 Engaging Poems for Two Voices with Motivating Activities That Help Students Improve Their Fluency and Comprehension (2009), with Tim Rasinski and Gay Fawcett. In 2020 he became the first recipient of the Laura Ingalls Wilder Children’s Literature Medal.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.