This post was written by NCTE members Cody Miller and Christian Hines.

Questions about citizenship and structures of government have long been on the radar of English teachers. Lord of the Flies and Julius Caesar are frequently positioned in terms of civic life in classroom discourse, while the past decade has seen a rise in discussing dystopian governments due to the popularity of series like The Hunger Games and Divergent.

Both canonical and young adult literature can offer pathways into conversations and analyses of government functions. We would like to widen that conversation to incorporate comics and graphic novels as texts that open up dialogue about civic life with secondary students.

Popular American comics have long grappled with questions of citizenship, identity, and large-scale politics broadly. As literary scholar Ramzi Fawaz details in The New Mutants: Superheroes and the Radical Imagination of American Comics, ubiquitous superhero teams like the Justice League, the X-Men, and the Fantastic Four responded directly and indirectly to social movements of the 1960s and beyond.

This radical history of comics combined with calls for reimagining English language arts as a space for constructing new civic possibilities by scholars like Antero Garcia and Nicole Mirra positions newer titles in the Marvel universe as crucial pedagogical texts for our classrooms. We are not alone in seeing the potential of Marvel narratives and civic engagement. Psychology professor Justin Martin recently outlined how the cinematic adaptation of Black Panther can inform elementary civics education.

This work is urgent and vital in our current sociopolitical landscape as white nationalism continues to rise both nationally and globally. Strengthened attacks on voting rights in various states combined with the failed insurrection earlier this year paint a picture of a democracy far from what can be considered healthy. The need to interrogate, critique, and reimagine civic identity and activity is urgently needed in our public life and classrooms.

Please note that it is essential that we do not equate “civic engagement” with legal definitions of “citizenship.” Equating “civic engagement” with legal definitions of “citizenship” erases multiple communities, including undocumented students, who are leading one of the most important civic movements today.

We’re particularly interested in positioning newer narrative variations of iconic heroes in English curriculum. House of Powers and House of X, the recent installments of the popular franchise The X-Men, depict the titular mutants constructing their own nation state to avoid the discrimination and oppression they’ve faced since they first appeared in the series. Meanwhile, the Outlawed story arc finds adolescent superheroes like Miles Morales (Spiderman), Kamala Khan (Ms. Marvel), Riri Williams (Ironheart), and others being legislatively stripped of their superhero identities; their status as teen superheroes is constructed as an illegal identity by adult legislators.

Both series offer up models for how those with power construct who counts within the parameters of a nation state. Equally important, these comics demonstrate what happens to those who are considered outside the bounds of constructed citizenship.

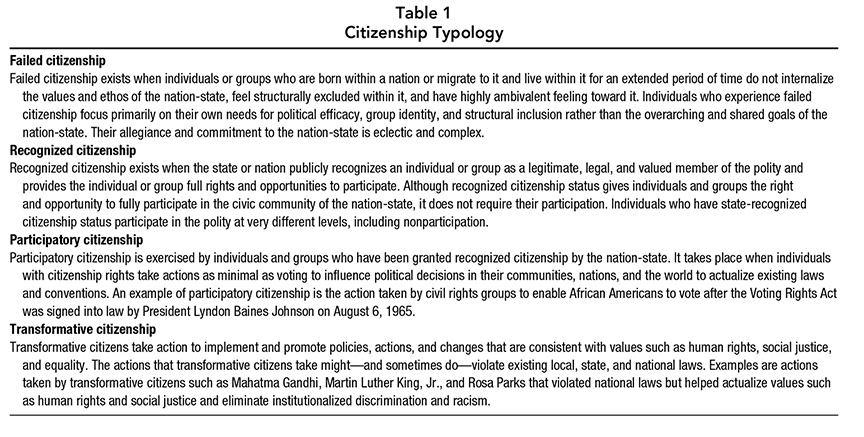

In teaching these comics, we believe students need language for considering the bounds of citizenship and civic identity. In “Failed Citizenship and Transformative Civic Education” [Educational Researcher, 46(7)], education scholar James Banks offers a framework for understanding types of citizenship enacted in nation states and perpetuated by public school curriculum that is valuable when teaching the Marvel titles we outline in this piece. Dr. Banks’s “citizenship typology” offers four distinct modes of citizenship that guide our thinking about teaching civics, graphic novels, and English language arts curricula. The typology is below:

House of X and Powers of X offer examples of transformative citizenship as a response to failed citizenship. The mutants are born in their respective nation states (X-Men has a range of characters from across the globe). Yet the various countries’ political systems work to deny mutants basic rights, even ranging to mutant genocide in some cases. As a result, some mutants form their own allegiances to create communities outside of their nation states throughout the history of X-Men. Perennial antagonist Magneto is the embodiment of this ethos while the sagacious leader of the X-Men, Charles Xavier, works to fold mutants into the nation state through ideas of tolerance and acceptance.

However, in House and Powers of X, Charles loses hope of this vision and works to create an island nation state (recognized by the United Nations) called Krakoa where mutants can live separate and ostensibly peaceful lives away from humans. This narrative history is not necessary to incorporate the comics into classroom discussions. House and Powers of X easily work as standalone texts. Teachers can open up questions regarding citizenship with the following questions that students can answer with textual evidence:

- How do characters understand their identity in relation to the nation state Krakoa?

- How are decisions made on Krakoa? Who is heard and who is maligned?

- How would you describe what life is like for people on Krakoa?

- How is Krakoa an inclusive space and how is Krakoa an exclusive space? How are ideas of citizenship expanded or limited in Krakoa?

- The Fantastic Four are not allowed on Krakoa due to their status as people who were not born with superpowers but developed powers due to external factors. How does this decision complicate the idea of transformative citizenship?

- In many ways Krakoa is a model of transformative citizenship. How might Krakoa be an example of failed, recognized, and participatory citizenship for other characters in the narrative?

The Outlawed saga offers examples of participatory and transformative citizenship when the Champions take action to defy the law that renders teen heroes as vigilantes and continue to save those who are at the greatest risk of being hurt, despite the government rendering them powerless. Crimes are still happening, and the teen heroes refuse to be bystanders. Their transformative action takes place when they accept that the laws that are dictated are not only harmful but meant to be used as tools to control and silence young people (by means of reformatory education) who are seen as a threat to those who are in power.

When the Champions decide to meet with United States government officials, they are met with resistance by local authority; but they have garnered support from their respective communities. Miles (Spiderman) and Riri (Ironheart) have to consider their community spaces when they are both deemed illegal heroes. Miles continues to patrol Brooklyn and risks arrest in order to ensure the safety of his neighborhood. Riri considers her family and what getting arrested would mean for her mother. She decides initially not to risk getting arrested so as not to bring negative attention to her community. Both Miles and Riri later decide that their cause extends beyond their local communities and both heroes decide to continue in their fight for justice by taking up their teen superhero mantles. Bringing their stories into the classroom can offer a space for discussion regarding:

- In what ways do narratives of teen superheroes challenge what we typically see in superhero media?

- In what ways do adults work to silence and curtail youth civic engagement? Why are adults concerned about youth civic engagement?

- How do educational systems and people within educational institutions attempt to stop efforts at transformative citizenship by young people? Why do adults not want to see young people enact transformative citizenship?

- How do laws and the legal system ensure young people do not have as much civic power as adults?

- In what ways do communities provide a space for youth to develop personal and political stances? How do communities provide models of citizenship outside the nation state? How can students’ funds of knowledge and community membership contribute to enacting civic engagement?

Considering the bounds of citizenship as both a physical and socio-political construct can support students in analyzing characters, discussing setting and its impact on characters, and connecting plot points across a text.

Additionally, positioning citizenship and civic action as a framework for analyzing literature can open up a space for students to make thematic connections between Marvel comics and more commonly taught print books in English classrooms. Positioning the Marvel titles we suggested in conversation with other texts in a broader curricular unit could be one way to approach the type of work we’ve outlined throughout this piece.

Outside of teaching comics, teachers should ask how schools can become an inclusive place to nurture and enact transformative citizenship. For starters, we can model ways of engaging our students in participatory and transformative citizenship. By working toward inclusion and youth activism we can cultivate spaces where student voices are amplified within the scope of school-based civic activities. This can be done by interrogating the range of student input on school policies and procedures via student council and student government or creating avenues of connecting students’ communities to their academic contexts with student-led community liaisons.

We can allow for participatory citizenship via classroom activities (e.g., creating a student-led survey to address school issues and concerns, a student-created school action plan, student documentaries on community histories and citizens). These actions and activities will facilitate our students’ need to be included in their schools’ overarching interests and goals, and it will help to develop strong student buy-in to their democratic educational pursuits.

Interrogating and critically questioning ideas of citizenship and civic life are imperative. Amanda Gorman’s “The Hill We Climb” became a moving symbol of democratic potential earlier this year. The poem speaks to ways English curriculum can be envisioned to discuss a more equitable civic life. As English teachers, we should heed the call. Educator Amber Cook (2021) reminded us in the wake of the insurrection and inauguration of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, “Amanda Gorman is in your classroom right now. Do your diligence to cultivate it” and “Insurrectionists were once in someone’s classroom. Do your work and teach antiracism.” These are the stakes and the possibilities.

Cody Miller is an assistant professor of English education at SUNY Brockport. During his seven years as a high school English teacher and in his current role, he positions texts as vehicles to discuss broader sociopolitical issues in students’ lives and worlds. Miller is chair of the NCTE LGBTQ Advisory Committee. He can be reached at hmiller@brockport.edu or on Twitter @CodyMillerELA.

Cody Miller is an assistant professor of English education at SUNY Brockport. During his seven years as a high school English teacher and in his current role, he positions texts as vehicles to discuss broader sociopolitical issues in students’ lives and worlds. Miller is chair of the NCTE LGBTQ Advisory Committee. He can be reached at hmiller@brockport.edu or on Twitter @CodyMillerELA.

Christian Hines is a doctoral student and instructor in the Department of Teaching and Learning at The Ohio State University. She is a former high school English teacher who believes in the transformative power of reading and in exposing students to a wide array of multicultural literature, engaging them in culturally inclusive reading materials, and empowering them with mentorship and community building. Twitter handle: @Mshines831.

Christian Hines is a doctoral student and instructor in the Department of Teaching and Learning at The Ohio State University. She is a former high school English teacher who believes in the transformative power of reading and in exposing students to a wide array of multicultural literature, engaging them in culturally inclusive reading materials, and empowering them with mentorship and community building. Twitter handle: @Mshines831.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.