This post is by NCTE member Anastasia Gustafson.

Just over a decade ago, young adult fiction was more than a cultural trend; it was a semi-cultish phenomenon that captivated the minds and wallets of a seemingly infinite number of young people. If not fresh in one’s memory, it might be easy to forget just how absolutely moving this time in YA publishing really was.

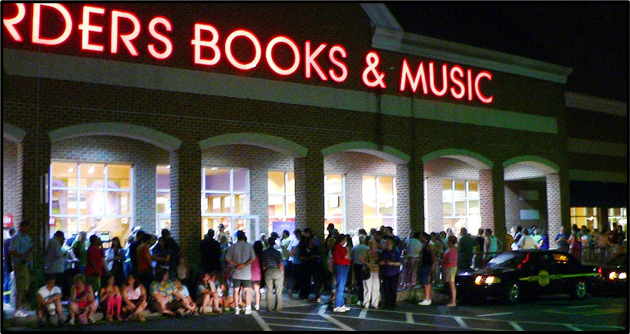

Maybe most prominently, the Harry Potter series sparked magical life into a reading revolution neither replicated since nor seen before in young people. When a new novel was released by J. K. Rowling, it kept young readers lining up outside of bookstores for hours on end.

Photo by Raul654 from Wikimedia Commons Depicting Harry Potter Fans Outside of Borders on July 16, 2005.

In response to the increasing popularity of this series, there was a time when some Christian parents led a book-banning crusade of sorts against the Harry Potter books because the texts were seen as both incredibly popular and possibly Satanic in nature. Parents were afraid the books might inspire young, impressionable children to try their hand at witchcraft.

But the concerned parents could not stop the movement; stronger than the Imperious Curse, young readers marched to the doors of bookstores willfully and without stammer. Young readers were so eager to get their hands on the books, in fact, that Barnes and Noble even began hosting midnight release parties. In Black Friday fashion—but in the middle of summer—the retailer would open its doors at midnight to long lines of young buyers who were eager to get their hands on the newest publication in the series.

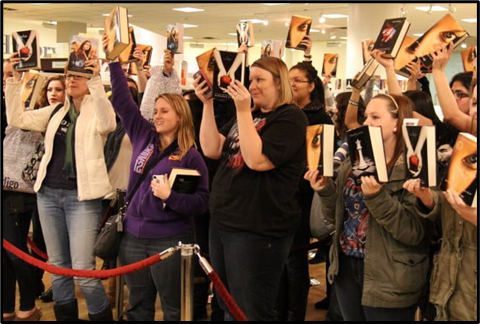

Then there was the unforgettable Twilight Saga, which clutched at the hearts of young female readers, who often bickered at lunch tables over perhaps the most potent YA fiction question ever posed: “Team Edward or Team Jacob?” It is hard to forget the screaming of young girls at the theaters, bookstores, and book-signing events.

Signing by author Stephenie Meyer inside Metrotown Vancouver. Photo from 604 Now, February 26, 2013.

In 2011, in the Atlantic, Alyssa Rosenberg wrote on the YA phenomenon, stating that Twilight and Harry Potter inspired a movement where “in the last decade, fans of all ages have flocked repeatedly to series aimed at young adults.” A genre meant for young readers bled into an audience much bigger than expected. The boom could not be contained.

Students at middle and high schools around the country took Divergent faction placement quizzes, and many English teachers added the books to their school’s curriculum after a hasty demand and uptick in the consumption of these popular novels. Seven universities even offered classes on Harry Potter, and Twilight became required reading at Ohio State University.

One of the more peculiar responses to the popularity of YA texts in the 2010s was how it inspired a generation of young mothers to begin naming their babies after their favorite books’ heroines. Katniss, Hermoine, and Bella were just a few of the names that received a surge in popularity during the era of 2010s YA fiction.

Of course, there were many more titles than just those from the Harry Potter, Twilight, Hunger Games, and Divergent series. Ender’s Game, The City of Bones, anything written by John Green, The Lightning Thief, and many other titles enchanted the minds of young readers just a few years ago. The list seemed to be endless.

But then, very quietly, young adult fiction seemed to fizzle out. Where did it go? And why did it go? Why has there not been a new rising YA star in nearly ten years?

Googling this question outright offers few leads. But as an English teacher myself, I have started to realize just how different readers of today are as compared with readers of “my time.” (I graduated high school in 2018, so I can at least say at this moment I am not too far removed from what high school felt like.) Still, with the COVID-19 pandemic, social media, and the fast pace of youth culture, years are more like decades in the measurement of how changing youth culture can be perceived.

Young readers who often pursue YA novels exist most frequently from grades 5 through 12. This 5–12 grade range is the group of students I will be speaking of when discussing “contemporary young readers.”

These students are drastically different from students ten years ago. Students today are behind where they should be, emotionally, socially, and academically, according to research done by the Brookings Institution.

“As we reach the two-year mark of the initial wave of pandemic-induced school shutdowns, academic normalcy remains out of reach for many students, educators, and parents. Students and educators continue to struggle with mental health challenges, higher rates of violence and misbehavior, and concerns about lost instructional time,” explain Megan Kuhfeld, Jim Soland, Karyn Lewis, and Emily Morton in their article, “The Pandemic Has Had Devastating Impacts on Learning. What Will It Take to Help Students Catch Up?”

Ask any educator currently planted in the classroom, and they will affirm that teaching post-Covid means working with students who lost learning time and socialization development during the pandemic.

The aforementioned study cites losses in reading scores, noting that “the average fall 2021 math test scores in grades 3–8 were 0.20–0.27 standard deviations (SDs) lower relative to same-grade peers in fall 2019, while reading test scores were 0.09–0.18 SDs lower. This is a sizable drop. For context, the math drops are significantly larger than estimated impacts from other large-scale school disruptions, such as after Hurricane Katrina—math scores dropped 0.17 SDs in one year for New Orleans evacuees.”

This might mean the books that worked for pre-Covid readers do not do the same things for those who are living in a post-Covid context. Sure, students should be challenged in the classroom by reading harder texts; many post-Covid students can certainly read Harry Potter books. But for pleasure, the texts read for fun ten years ago would be considered much harder to read by contemporary young readers. Harry Potter might simply be too challenging for contemporary young readers to find enjoyable.

So, maybe all students need is a large variety of easy-to-read YA novels? Researching this concept, however, also tends to lead toward more questions than answers.

There is no shortage of newly published YA novels. Further, YA novels come in all Lexiles, secondary genres, and styles. So, is it an accessibility problem? Maybe a little. A large part of YA fiction exists in the 700s Lexile, which might alienate readers who were left behind during the Covid era. But if that were the heart of the problem, teachers would simply see their ninth graders eagerly reading a new version of something akin to The Boxcar Children. If there is not a large accessibility problem, what else could it be?

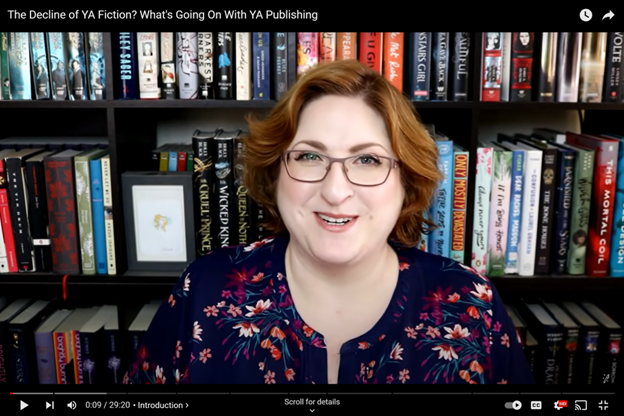

One person on the internet seems to think she has an answer to this question. Alexa Donne is an author, blogger, YouTuber, and graduate of Boston University who works in TV marketing, among other ventures. In her 2020 video, “The Decline of YA Fiction? What’s Going On with YA Publishing,” she offers many valuable insights as to why YA fiction is fading out of pop culture.

“The reality is the industry is shifting. YA has been saturated for a while, and what that means is too many books being published. They’re not selling enough, and the category has needed to pull back for some time. The brakes have been applied. . . . This has been going on for years,” Donne explains.

When considering whether the pandemic is the outright cause for the slump in YA, she has a firm response.

“Covid just hastened some things that were already happening. We started naturally reaching a [genre] saturation point about five to six years ago. The YA landscape of purchasing from 2008 to 2012 is the height of the boom. That’s when a ton of writers got their foot in the door. That’s when a ton of books broke out and created big careers for people,” Donne says in her video.

In essence, the genre was young, new, and exciting ten years ago. The marketing was enticing; these were books for young people, but not children. That drew readers in. Publishing companies saw this as a moneymaker and bought as many book contracts as possible from writers as they hoped to publish the next Twilight or Harry Potter. A decade after the major boom, the shiny YA label is not as exciting as it used to be.

Oversaturation of YA, pandemic learning deficits, and Lexile accessibility are all pieces of the puzzle. But there is something else lurking in the background that simply cannot be ignored when considering why YA fiction—or reading in general—is falling out of popularity: young contemporary students are becoming less interested in reading for pleasure at all.

“The shares of American 9- and 13-year-olds who say they read for fun on an almost daily basis have dropped from nearly a decade ago and are at the lowest levels since at least the mid-1980s, according to a survey conducted in late 2019 and early 2020 by the National Assessment of Educational Progress,” explains Katherine Schaeffer, writer for the Pew Research Center.

Reading for fun has been pushed out by something else. This answer, if one is a parent or teacher or works with children in any capacity, is often an insatiable appetite for technology.

“Our addiction to technology has massively impacted our attention spans and how we retain information. We are so easily distracted that no longer is it a simple task to sit and read a book. Our brains have adapted to this new digital age with constant short bursts of information instantly available,” explains Saorise Mullan in her essay “Is the Rise in Technology Causing a Decline in Our Reading Habits?”

YA fiction is indisputably fading from pop culture. For over ten years now, there has not been a rising star who can compete with the popularity of Twilight, Harry Potter, or the Hunger Games as they existed in the 2010s. However, this shift is a symptom of something much larger than young readers moving from one genre of interest to another.

There is a systemic and multifaceted issue at hand. Young people are spending more and more time on social media, which shortens their attention spans and deters their interest in reading a long and mentally demanding text. The pandemic left children far behind their predecessors academically, socially, and emotionally. In addition, there is an oversaturation of YA texts that struggle to meet contemporary young readers where they are.

These issues are pieces of a puzzle that English teachers, authors, and parents must grapple with if they want to spark the interest in reading observed just a decade ago in young readers. Solutions to these complex challenges will not be easy. Things we can do to start include distancing students from technology, providing additional academic support in English classrooms and at home, and searching for texts that resonate with readers.

Hope for the love of reading is not lost. John Green said in his new book, The Anthropocene Reviewed, that it seems art is not optional for human beings. As English teachers, we already know this inherent necessity is true of reading.

Anastasia Gustafson is an English teacher and basketball coach at Carmel Catholic High School in Mundelein, Illinois. She composes her own graphic novels and works as a freelance artist when she is not in the classroom.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.