This is an excerpt from Xiaoying Zhao’s article, “What Kinds of Agents? A Framework for Creating Inclusive Classroom Libraries.” In this article, she introduces a framework of six types of agents in children’s books, presents the findings from reviewing a set of 49 picturebooks, and provides practical suggestions for educators to create classroom libraries in which all types of agents are equally included.

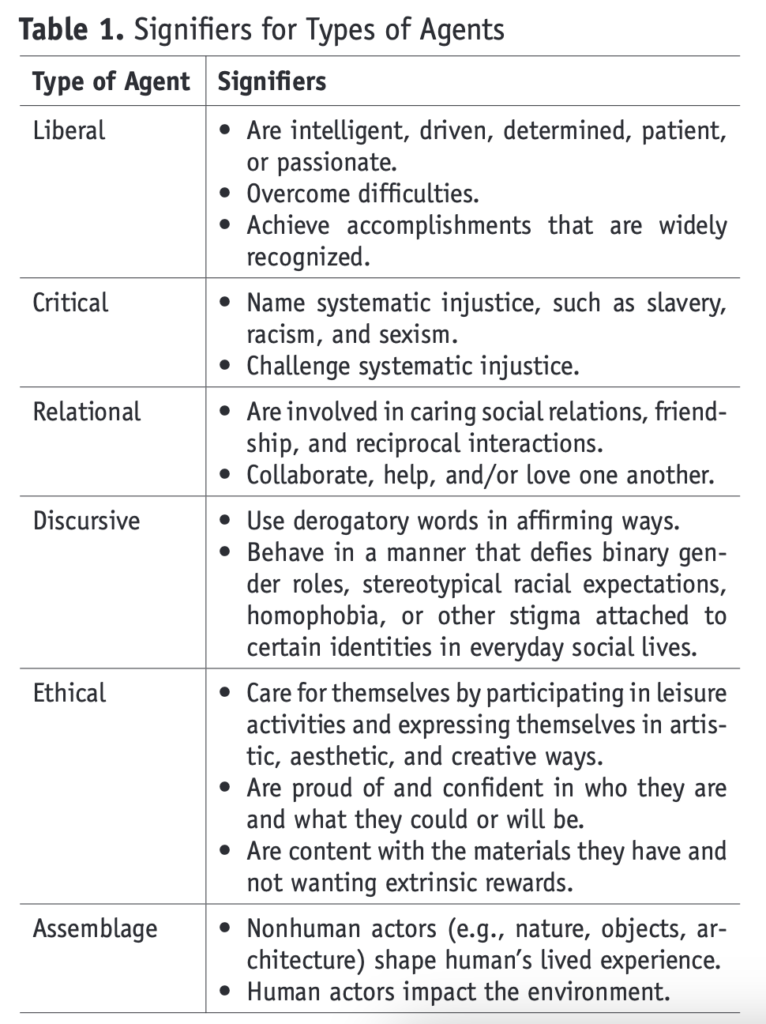

Agency is broadly understood as an essential characteristic of humans that does not require much explanation or theorization. I created a framework of types of agents to help educators include a balanced representation of agents in their classroom libraries, which could offer “windows and mirrors” that empower children to reach their fullest potential. The framework of agents includes liberal, critical, relational, discursive, ethical agents, and assemblage. Each kind applies to subjects situated in specific paths to certain purposes, in varied social relations, in different power relations, with unique language and body styles, and in differing relations with the natural, physical world. Table 1 details the characteristics of each kind.

The framework of six kinds of agents pinpoints varied possibilities that young readers can embody: overcoming challenges to achieve their goals; combating inequalities; building meaningful relationships with others; disrupting identity norms; caring for themselves; and being entangled with environments, objects, and other nonhuman agents. Who the characters are and what they do both impact what readers believe they can and should do. This framework allowed me to critically review the collection of 2019 social studies trade books for K–2 students. The disproportionate underrepresentation of critical and ethical agents in the collection is a reminder to teachers and librarians of the voices and experiences that are often marginalized in children’s literature. The following are my suggestions for educators to create an inclusive classroom or school library and develop character studies that focus on challenging injustices that children encounter in society today.

First, a critical review of agency through book characters can serve to counter white supremacy, as educators can intentionally select more books with critical agents and Black, female liberal agents. All citizens should “get in good trouble, necessary trouble,” as John Lewis suggested, and become agents of change. To help achieve democratic ideals, schools need more texts with critical agents like these to inform children about naming inequities and using dissent for social justice. To empower children of color, we must include more books about how people of color have stood against racism, worked together, and effected changes. For Black girls, who are under double oppression inside and outside of school, we must present more critical and liberal agents as role models to whom they can relate. All children, especially those who have been marginalized through identity stereotyping, can see themselves in the critical agents who challenge racism and sexism or the liberal agents who overcome constraints on the way to their personal goals. With scaffolding, children can examine literacy critically. When reading books with critical agents, educators can explicitly guide students to disrupt the commonplace and focus on the sociopolitical by asking the following questions:

- Who are the agents in this book? What kinds of agents are they? What are the relationships between them and the groups they represent?

- Do the characters support or disrupt power relations? What do they do?

- Why do you think the author(s) wrote this book? What do you think the author(s) think(s) about you, the reader?

Second, educators can include more books with discursive and liberal agents who identify as queer, who come from LGBTQIA+ or nonnuclear families, who have disabilities, who are economically underprivileged, or who come from other countries and regions. If we guide students to deconstruct assumptions about what is normal and what a normal person can achieve, they will have an open mind and begin to eradicate the stigma attached to people from underrepresented communities. Educators may ask the following questions to elicit children’s critical thinking:

- What similarities do you and the characters share?

- How are the characters different from you? What are their strengths? What do you think about your differences?

- Some people like these characters experience ridicule from others. Do you think that is fair? Why? How do you think mocking comments make the characters feel? What would you like to say to the characters? What would you like to tell those who look down on the characters?

Third, having more books with relational agents who build intergroup connections and ethical agents who care for and affirm themselves could encourage children to appreciate their own being-in-the-world and actively engage people from different sociocultural groups. Living in an increasingly diverse world, children encounter more diverse people, either directly or through media. Stereotypes, misconceptions, and close-mindedness could undermine their self-esteem and self-worth and hinder their ability to create and maintain meaningful connections with people from different backgrounds. More books affirming varied identities and intergroup relations are likely to motivate and guide children’s interactions with those who have differences in values, traditions, lifestyles, religions, and capabilities. Such interactions are critical to increase cohesion in the multicultural world.

Classroom teachers and librarians can use this framework of agents and their signifiers to reflect on the types of agents in their own book collections for young readers. They can analyze the characters and their actions, and use the characteristics and example books to classify what types of agents they are. Especially when selecting from books featuring the same characters, educators can apply this framework to differentiate them and make intentional decisions for their students. By comparing the numbers of agents of each type, educators can easily see what agents are over- or underrepresented. They can then pick more diverse, inclusive books so children will learn how to coexist with others in this world in ethical and equitable ways.

Dr. Xiaoying Zhao is an assistant professor of early childhood education in the School of Teaching and Learning at Illinois State University. Her research interests include critical literacy, children’s agency, and civic education.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.