This blog post was written by NCTE member R. Joseph Rodríguez as part of a blog series celebrating the National Day on Writing®. To draw attention to the remarkable variety of writing we engage in and to help make all writers aware of their craft, the National Council of Teachers of English has established October 20 as the National Day on Writing®. Resources, strategies, and inclusion in a blog post does not imply endorsement or promotion by NCTE.

This blog post was written by NCTE member R. Joseph Rodríguez as part of a blog series celebrating the National Day on Writing®. To draw attention to the remarkable variety of writing we engage in and to help make all writers aware of their craft, the National Council of Teachers of English has established October 20 as the National Day on Writing®. Resources, strategies, and inclusion in a blog post does not imply endorsement or promotion by NCTE.

April (student, pseudonym): “Who’s gonna wanna read my writing? Tell me.”

Me: “I’ll read your writing. I wanna read what you’re thinking. I really do, April!”

I began my teaching career in the 1900s, and decades later students still want to write today.

They do!

My years of teaching always bring some laughs and surprises to my high school students.

And I keep teaching and writing—even across two centuries. Imagine!

Students write if we invite and encourage them to do so. I learned this from my own teachers while attending the public schools of Houston, Texas, and years later when I pursued my teaching certificate.

When I was introduced to the writings of Donald H. Graves, I learned that I must “encourage writing” among my students because they have something to say that reveals their self-determination, concerns, and brilliance (76).

Youth Scribes

Through the years I’ve gotten to know students better by listening to their ideas on the page, screen, and canvas. Every student has the capability to express their ideas as a scribe, and as their teacher I can influence their writing ideas and goals.

My years of encouraging students to write has led me to make their writing interests and moves more visible to teachers in our profession. In Teachers Speak Up! Stories of Courage, Resilience, and Hope in Difficult Times, Sonia Nieto and Alicia López Nieto note, “We know that most teachers rarely get to tell their own stories, particularly pre-K–12 teachers who work in public schools” (1). This resonated with me after reading articles and listening to news stories that missed the points of view held by students and teachers in schools.

In 2021, each school day I documented what students did that got them writing. As a result, over a three-year period, I gathered and assembled my notes into what became the book Youth Scribes: Teaching a Love of Writing.

In 2021, each school day I documented what students did that got them writing. As a result, over a three-year period, I gathered and assembled my notes into what became the book Youth Scribes: Teaching a Love of Writing.

My use of the word scribe refers not only to the ancient practice that predates the printing of writing and the creation of manuscripts and maps, but also to the modern forms of communications we practice today (Rodríguez). For instance, students can experience editing, transcription, and interpretation to show understanding across various audiences, cultures, disciplines, modes, and situations. Rhetoric comes alive and gains relevance for my students as they come of age.

The ancient practice of scribes can become a scribal rite of passage for our students today. In fact, student scribes surround us if we pay attention to them and take notice. Their engagement involves devices, and they want to be scribes who engage in these acts: handwriting (print, cursive), typing, audio recording, video recording, drawing, and verbalizing their responses—if we invite them to do so and beside us, too.

Writing is interconnected to reading; both rely on scribes making meaning for understanding. As a teacher-poet and scribe, I connect with Graves’s view as I work beside my students: “The reader and myself as writer wilt under the weight of words” (266). The heaviness of words can be daunting to us and our students, but it also leads to the making of sentences and wonderment.

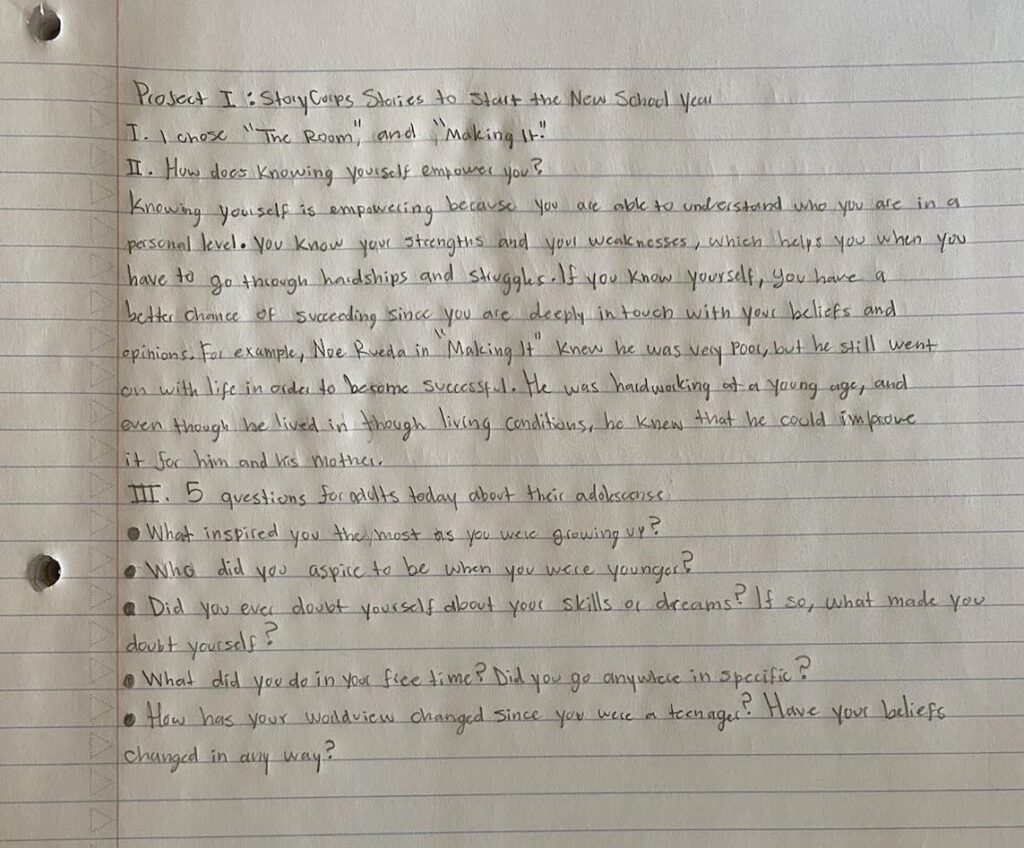

Students often ask me where the words come from that I write into poems or books, or how the ideas may have begun for the authors of young people’s literature we study. One student, Katherine, dived into the StoryCorps audio recordings titled “The Room” and “Making It” and then drafted questions for a conversation with an adult. Her reflections reveal her inquisitiveness and sense of self.

Katherine examined two StoryCorps selections and prepared questions to ask an adult about their adolescence.

Where do the ideas form first? When does an actual story start? How do you know? Or how does one create with ideas, images, or words? My students’ inquiries guide me to find answers with them.

Scribal Inquiry

“How do we keep doing this—making art?” asks Stacey D’Erasmo in The Long Run: A Creative Inquiry (3). When I heard April’s questions (see epigraph above), I was reminded of D’Erasmo’s question to her readers.

Students who attempt writing sometimes demand I tell them how much they need to write to get by or how many pages they must produce for a specific [passing?] grade.

How do I keep them going and writing in their own thoughts—free from or assisted by AI? AI can be a springboard for ideas, but it can also be limiting to demonstrating one’s own conceptual thinking. Some students want to know for whom they are writing in the first place. Would it matter to the world what I write? they seem to be asking.

Yes, yes! I tell them, although their question comes to this: Who cares, anyway?

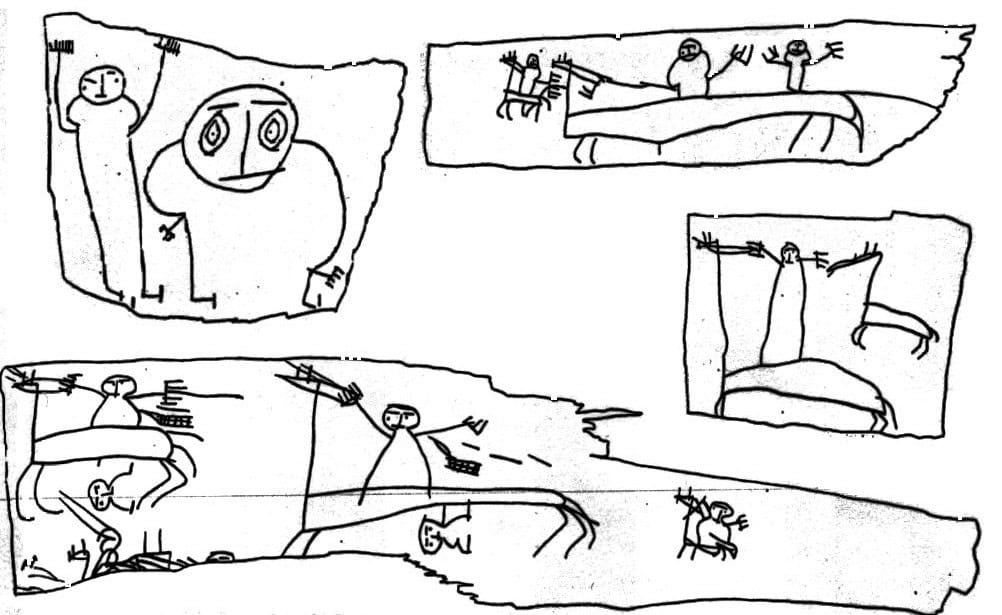

And then I introduce them to the schoolboy Onfim’s sketches, which Onfim drew on birch bark in the 1200s. Can you believe it?

Onfim lived in Novgorod, or present-day Russia. His drawings show school notes and homework exercises scratched on bark later preserved in clay soil (Andrei). He was possibly six or seven years old. Onfim drew battle scenes that depict him and his own teacher in action. His sketches demonstrate his knowledge of an alphabetical system as well as his young imagination and inventiveness.

Onfim’s drawings tell stories. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

I find it revelatory that Toni Morrison explains, “A writer’s life and work are not a gift to mankind; they are its necessity” (ix). I think about the necessity of our students as scribes in our classrooms and in the changing world as well as the scribes before them—across civilizations and cultures—who circulate many ideas for our understanding, self-determination, and agency as thinkers and artists.

Indeed, there is work to be done: we must write and act with our students.

We can do it.

We must write right now and with them.

Write on!

Joseph Rodríguez is a secondary language arts teacher at William Charles Akins Early College High School in Austin, Texas. He is the author of Enacting Adolescent Literacies across Communities: Latino/a Scribes and Their Rites, Teaching Culturally Sustaining and Inclusive Young Adult Literature: Critical Perspectives and Conversations, and This Is Our Summons Now: Poems. Joseph is a former editor of English Journal and founder of the literacy initiative Libre con Libros. He and his students are avid readers of banned and challenged books.

Joseph Rodríguez is a secondary language arts teacher at William Charles Akins Early College High School in Austin, Texas. He is the author of Enacting Adolescent Literacies across Communities: Latino/a Scribes and Their Rites, Teaching Culturally Sustaining and Inclusive Young Adult Literature: Critical Perspectives and Conversations, and This Is Our Summons Now: Poems. Joseph is a former editor of English Journal and founder of the literacy initiative Libre con Libros. He and his students are avid readers of banned and challenged books.

References

Andrei, Mihai. 2024. “These Drawings Were Made by Onfim, a 7-Year-Old Boy in the 13th Century.” ZME Science. 24 July 24. www.zmescience.com/science/archaeology/drawings-onfim-novgorod/. Accessed 11 September 2024.

D’Erasmo, Stacey. 2024. The Long Run: A Creative Inquiry. Graywolf Press.

Graves, Donald H. 2003. Writing: Teachers & Children at Work, 20th Anniversary Edition. Heinemann.

Keefe, Rugenia, and Cole Phillips. 2020. StoryCorps. “At the End of High School, a Special Kind of Thank You.” June 19. www.storycorps.org/stories/at-the-end-of-high-school-a-special-kind-of-thank-you/.

Morrison, Toni. 2019. The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations. Knopf.

Nieto, Sonia, and Alicia López Nieto. 2024. “Introduction.” In Teachers Speak Up! Stories of Courage, Resilience, and Hope in Difficult Times, edited by Sonia Nieto and Alicia López Nieto. Teachers College Press.

Rodríguez, R. Joseph. 2025. Youth Scribes: Teaching a Love of Writing. Heinemann.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.