This post is written by member Kaylin Upah.

“Should she be teaching these students to write poetry when they need to know how to defend themselves from someone beating them up? Can a memoir by Malcolm X or a novel by García Márquez save them from the daily blows? And what about those who have such learning problems they can’t even manage a book by Dr. Seuss, but can weave a spoken story so wondrous, she wants to take notes. Should she give up writing and study something useful like medicine? How can she teach her students to take control of their own destiny? She loves her students. What should she be doing to save their lives?”

Sandra Cisneros, Introduction to The House on Mango Street, xviii-xix

On my first day of student teaching in seventh grade, our language arts class appropriately reads Gary Soto’s Seventh Grade, a short story about a boy named Victor who pretends he can speak French in order to impress his crush on the first day of school.

I read the story aloud to the class: “There were rivers in France, and huge churches, and fair-skinned people everywhere, the way there were brown people all around Victor.”

One of my students raises their hand. “Isn’t that racist?” He is not trying to be funny or offensive; he is honestly curious if it is racist for Soto to describe the color of skin of the people in his story.

Sometimes, teachable moments like this happen when we least expect them. It is clear that the student in my class does not have a clear understanding of what the term “racist” means. Although I can explain this to the student in a minute or less and move on with the story, the concept of racism is an important, complex conversation that will continue throughout the rest of the year.

There are people who would be surprised to hear that topics like racism arise in a seventh-grade classroom. In the stereotype of a seventh grader, people tend to belittle the “struggles” of adolescents to things like puberty, first kisses, and remembering to apply deodorant after gym class.

Yet life for a seventh grader in 2017 is more complicated than we know.

At the age of 12, there are students in my class who live with their grandparents because their parents have committed suicide. Another lives with his 18-year-old sister because his mom is in a mental institution and his dad is an alcoholic. Others struggle with depression, receive threats from their peers that they will be beaten up after school, and experience racism on a daily basis.

So, as Sandra Cisneros asks in her introduction to The House on Mango Street, what should we be doing as English teachers to save the lives of our students?

We need texts that demand action.

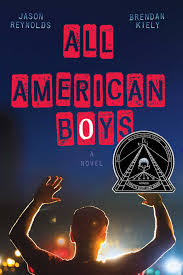

One text that could be particularly helpful is All-American Boys, a novel by Jason Reynolds and Brendan Kiely. In this novel, a white high school student named Quinn watches a cop severely beat a black student named Rashad outside of a gas station for a crime he didn’t commit.

After Quinn chooses to not do anything, another black student tells Quinn, “White boy like you can just walk away whenever you want. Everyone just sees you as Mr. All-American boy, and you can just keep on walking, thinking about other things. Just keep on living, like this shit don’t even exist” (Reynolds & Kiely, 176).

How many times do we as teachers walk away from hard questions and teachable moments whenever we want?

All-American Boys is a text that shows teachers and students that silence is not an option. It forces us to reflect, discuss, and act. How do we define racism in 2017? Does it still exist today? Will it always exist? What is white privilege? And what do we do about all of this?

As English teachers, it is not our job to know the answers to these questions. It is not our input that matters most. Rather, the most important role we have as English teachers is to show our students how they can share their thoughts, experiences, and voices with each other and the rest of the world.

There are a few ways we can go about this:

- Build an environment of respect.

The most meaningful, authentic learning experiences about topics like racism come from conversations where people can openly share their opinions in a safe place. We must embrace challenging and sometimes uncomfortable dialogue in our classrooms, where students can share without the teacher’s nod of approval, without the fear of being wrong, and without the stress of grades.

- Let your classroom become an outlet for free expression.

Allow your students to discuss and write about injustice they have felt in their own lives or witnessed in the lives of others. Introduce them to texts and authors that ignite conversation and fuel writing.

- Teach your students to share their voices with the world.

Once they have had the opportunity to share with each other, show students mediums they can use to share their voices outside of the classroom walls. By introducing students to blogging, spoken word, and advocacy journalism, we are teaching our students tools to express themselves to a wider audience. Teaching persuasive writing and speaking techniques can also help students in the delivery of their messages.

As a student teacher, these are a few goals I have for my future classroom, but I fully intend to make this vision a reality. It is funny how things like spelling mistakes, vocabulary lessons, and rubrics suddenly seem so insignificant when you start teaching what matters most. Let’s not be silent in our classrooms; let’s redefine what it means to be an “All-American” teacher in 2017.

Kaylin Upah is currently a student teacher in 7th grade language arts in Colorado Springs, CO. She enjoys books, travel, hot yoga, and lots of coffee.