This post was written by NCTE member Cody Miller.

With the surge of youth activism making headlines across the nation, along with the vitriolic backlash to said activism, it is a ripe time to examine how “youth” exists as a social and cultural construct.

Drawing on Nancy Lesko’s Act Your Age!: A Cultural Construction of Adolescence, this analysis would have us think how, historically and socially, the concept of “youth” has been created by political and cultural institutions. In order to study the social and cultural construction of youth, we must first honor the interests of today’s youth, which requires us as educators to challenge, deconstruct, and reconstruct the canon with our students.

The focus of February’s NCTE chat was the “Canon of Our Community,” which called on educators to reimagine the purpose, content, and form of the canon in order to “celebrate the voices of our students and honor the literacies of their communities.”

As Perry and Stallworth (2013) note, today’s student “thinks from multiple perspectives, partially because of the advancements in technologies, but also because of the diverse society America itself has become” (p. 16). These advancements in technology should prompt us educators to expand the form of texts we study as well. Television, video games, music, and other digital and nonprint texts are just as worthy of critical analysis as traditional print texts. For too long, white, cisgender, heterosexual male standards have dominated what and who is deemed worthy of canonical status.

As English teacher and critical pedagogue Julia E. Torres notes in her examination of AP course content, the powers that deem a text “canonical” are “not the ones teaching the texts to high school kids” (April 14, 2018). Torres then calls for a reconstruction of the canon with students and teachers working as the coauthors.

Torres’s call echoes author Jason Reynolds’s assertion that educators need to “expand” the literary canon to honor the full range of texts, authors, and topics that young people are already critically consuming. These calls to action should be centered in the way we teach English and the ways in which we prepare the next generation of English teachers. It is my belief that we cannot analyze youth culture if we marginalize and ridicule texts that youth consume in their lives as lacking merit.

The texts young people consume have merit; the fact that young people are engaging in the texts is the merit.

This school year, I created a unit for my ninth graders that focuses on the study of youth. This unit was inspired both by youth activists across the nation and a presentation I attended at last year’s NCTE Annual Convention in St. Louis entitled “Using YA Lit and a Youth Lens to Promote Student Voices in the Classroom” (Hinton-Johnson, Roseboro, Arenas, Shafqat, & Wilmot, 2017).

In the unit, we explore how youth is positioned, constructed, and altered in our culture and society. The driving questions of the unit are

- How is youth socially and culturally constructed?

- How do social and cultural constructions of youth intersect with other identities? How do those intersections relate to power dynamics?

- How has youth historically been socially and culturally constructed?

- What differences exist between sociocultural understandings of youth and biological understandings of youth?

- How can texts challenge or confirm dominant sociocultural views of youth?

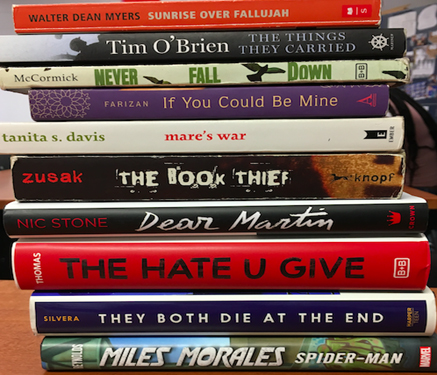

Students select one anchor book from the list represented in the stack here to read throughout the unit.

Then, as a class, we watch several television shows spanning the decades in order to analyze how youth has changed throughout generations. We watch contemporary shows like Grown-ish and On My Block as well as older shows like Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, Daria, and the Degrassi series (Yes, I do feel my age when I categorize shows I grew up with as “older.”).

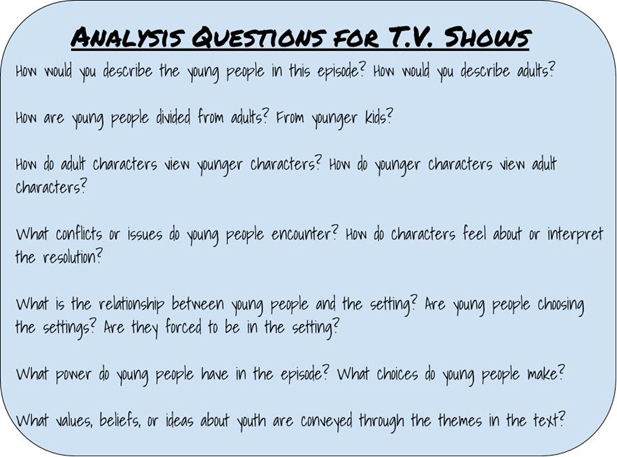

Then we analyze the shows using the guiding questions included here. They were adapted from an article by Petrone, Sarigianides, and Lewis (2015).

Finally, we read nonfiction texts that illuminate how youth has been socially and cultural situated throughout the history of the United States.

As we analyze the various texts, we consider how this text either challenges or confirms dominant views of youth. It is also important that we do not isolate “youth” as a singular identity. As writer Ijeoma Oluo illustrates, systemic racism denies Black and Brown youth the rights “to be kids” and robs Black and Brown youth of the right to “look fondly on their teenage hijinks—because these get them expelled or locked away” (2018, p. 133).

We cannot ignore the reality that “teenage hijinks” and carefree youth are realities to those with privileged identities. Students should critically examine how youth intersects with race, gender, sex, sexuality, class, and other identities that characters inhabit to address how “multilayered structures of power and domination” shape the experiences of young people (Cho, Crenshaw, & McCall, 2013, p. 804) . Indeed, reconstructing the canon allows for the voices of marginalized youth to be centered and studied in the classroom.

I am not advocating for full abandonment of “classic” texts. In fact, Romeo and Juliet makes for an excellent case study in discussing social and cultural constructions of youth. Rather, I am suggesting we challenge systems that get to define who and what composes the canon and vigorously coconstruct a new canon with students. A new canon would include everything from Shakespeare to stand-up comedies; from poems to tweets; from amended AP prompts to young adult literature. In studying youth culture through a new canon, we challenge the notion that the canon is static.

In fact, we reimagine a canon that is living, breathing, dynamic, and reflective of the world our students live in. Additionally, we move from viewing youth in deficit-centered discourses to understanding youth culture as something worthy of analysis within a classroom space.

For more readings on using youth theory in English language arts classrooms, educators should read Rethinking the “Adolescent” in Adolescent Literacy by Sophia Tatiana Sarigianides, Robert Petrone, and Mark A. Lewis, which was recently recommended as a summer professional development text by NCTE.

References

Cho, S., Crenshaw, K., & McCall, L. (2013). Toward a field of intersectionality studies: Theory, applications, and praxis. Signs, 38(4), 785–810.

Hinton-Johnson, K., Roseboro, A., Arenas, S., Shafqat, S., & Wilmot, R. (2017, November). Using YA lit and a youth lens to promote student voices in the classroom. Panel discussion at the National Council of Teachers of English Annual Convention, St. Louis, MO.

Lesko, N. (2012). Act your age!: A cultural construction of adolescence (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Oluo, I. (2018). So you want to talk about race? New York. NY: Seal Press, Hachette Book Group.

Perry, T., & Stallworth, B. J. (2013). 21st-century students demand a balanced, more inclusive canon. Voices from the Middle, 21(1), 15–18.

Petrone, R., Sarigianides, S. T., & Lewis, M. (2015). The youth lens: Analyzing adolescence/ts in literary texts. Journal of Literacy Research, 46(4), 506–533.

Reynolds, J. (2018, January 23). Interview with Trevor Noah. The Daily Show with Trevor Noah. Retrieved from http://www.cc.com/video-clips/avk8pe/the-daily-show-with-trevor-noah-jason-reynolds—serving-young-readers-with–long-way-down-

Sarigianides, S. T., Petrone, R., & Lewis, M. (2018). Rethinking the “adolescent” in adolescent literacy. Urbana, IL: NCTE.

Torres, J. (2018, April 14). Literary canon-boom! #educolor [Blog]. Retrieved from https://juliaetorres.blog/2018/04/14/literary-canon-boom/.