This blog was written by Elisa Wainsgort and the NCTE Standing Committee on Literacy Assessment.

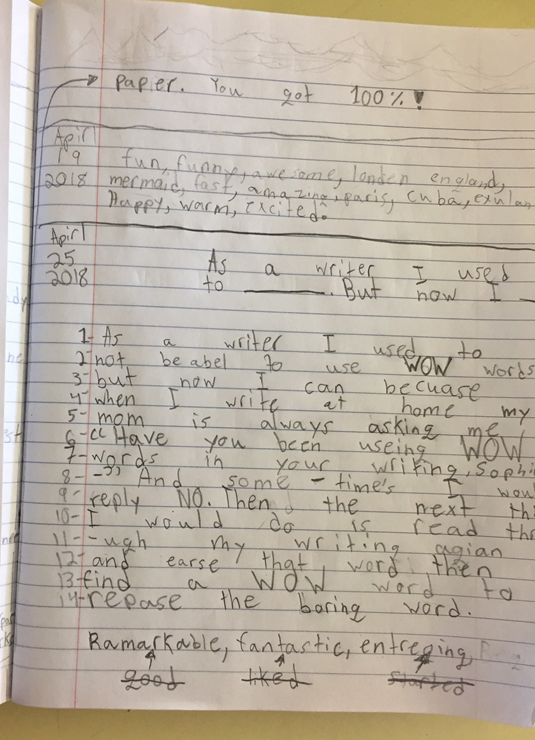

“I used to . . . but now I . . . .”

It is not a secret that classroom assessment practices can either enhance or hinder student learning and growth.

More often than not, external assessments are quantitative in nature and don’t tell a story of students’ learning over time. They certainly don’t tell a story from the point of view of the person most vested in the results: the student.

Classroom-based assessments paint a more accurate picture of what our students know and are able to do even if teachers are restricted to school or district mandated assessment tools that give students little or no voice over their own learning journey.

Classroom-based assessments provide valuable information about student learning that teachers, students and families can use to enhance and extend learning precisely because they take into account the learner and the context in which the learning took place.

More importantly, if we are going to permanently change the conversation around classroom assessment practices and beliefs, then we need to get serious about adopting practices that include students in their own learning and that are easily and convincingly communicated to all stakeholders, especially the families of our students.

As classroom teachers, we must challenge assessment practices that do little to inform us or our students and their families of what students are doing and what they have learned as a result of engaging in classroom learning events. As the NCTE/ILA Standards 2 & 3 emphasize, “the teacher is the most important agent of assessment” and “the primary purpose of assessment is to improve teaching and learning.” If neither of these conditions is in place, then our assessment efforts will not bear fruit.

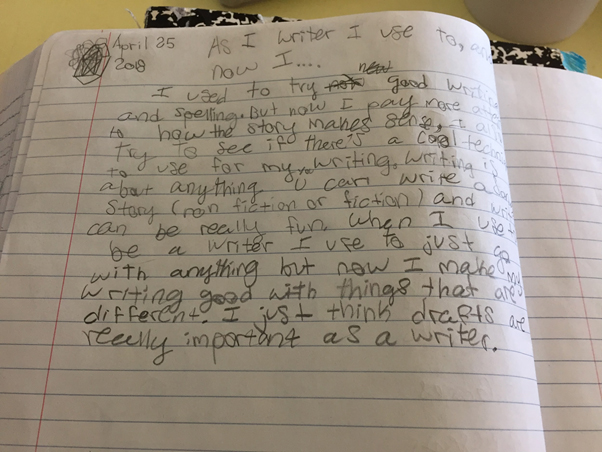

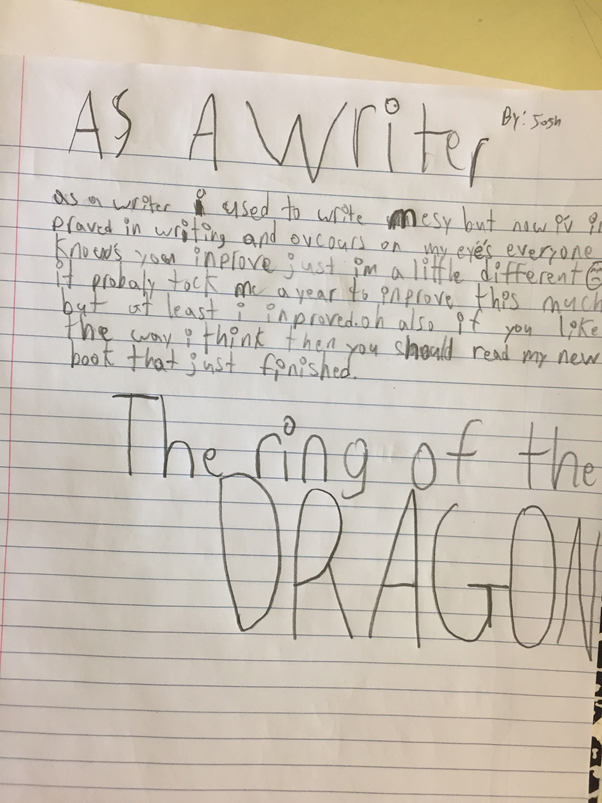

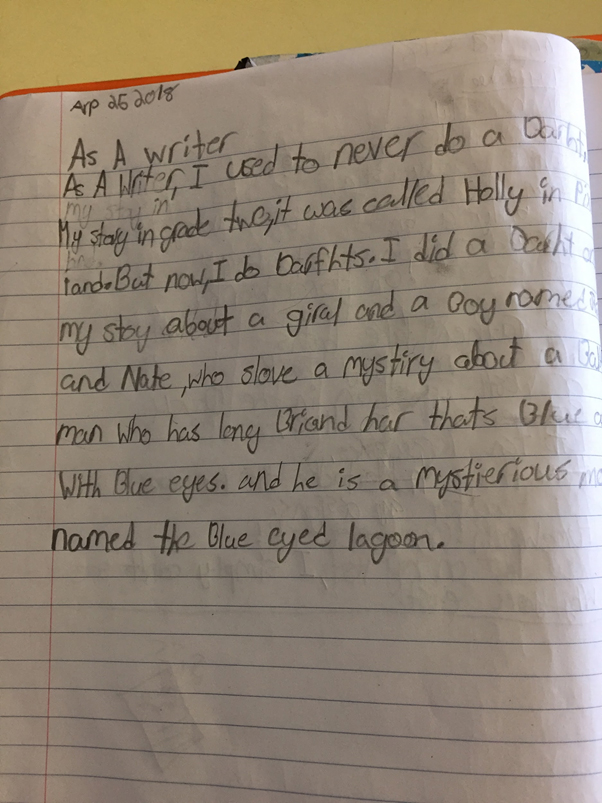

One practice that holds promise, though surface level simplicity may fool us into thinking that there’s nothing of value to look at, is to ask students to think about their learning over time in terms of “I used to . . . but now I. . . . ”

These statements allow students to think about a body of work over time. They can compare what they were doing as writers in September, for example, with what they are producing in December, and be able to affirm growth on their own terms or recognize that there hasn’t been much change during those few months of school.

Either way, this opens up possibilities for conversations with students and families, especially if these are timed right before parent-teacher interviews and/or student-led conferences. During the course of the school year, a record of these self-assessments could relate an important story about learning from the perspective of the student. If the teacher and possibly the student’s family also engage in this assessment process, we would have a rich story of a child’s year of learning as a writer. This would enhance and position student learning more authentically than using rubrics or checklists that are used primarily for evaluation purposes, such as a mark on a report card.

This assessment stance can be adapted and used at any grade level and in any discipline. Any time students take a look at where they’ve been and where they are as writers, readers, scientists, mathematicians, and learners, they are able to affirm the progress they’ve made and plan for next steps in learning. This can easily be adapted by changing “I used to. . . but now I . . . ” to “I used to think . . . but now I think. . . . ”

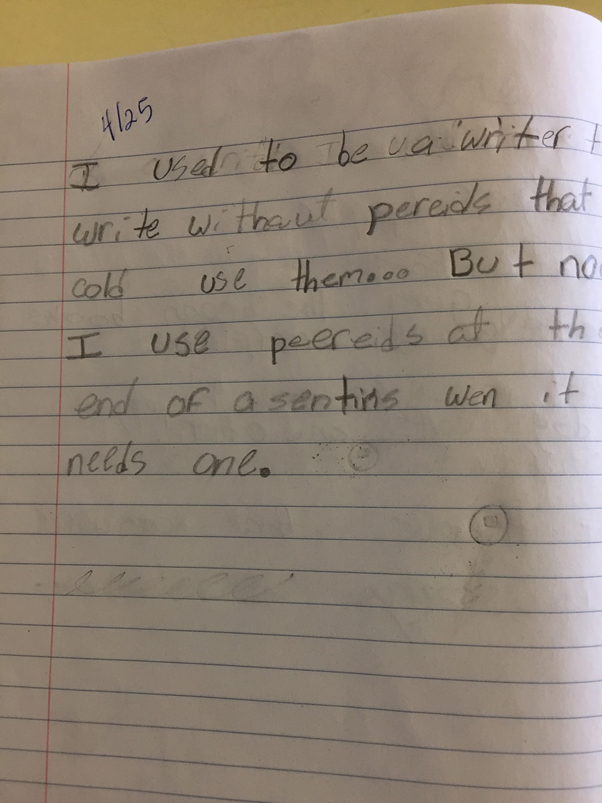

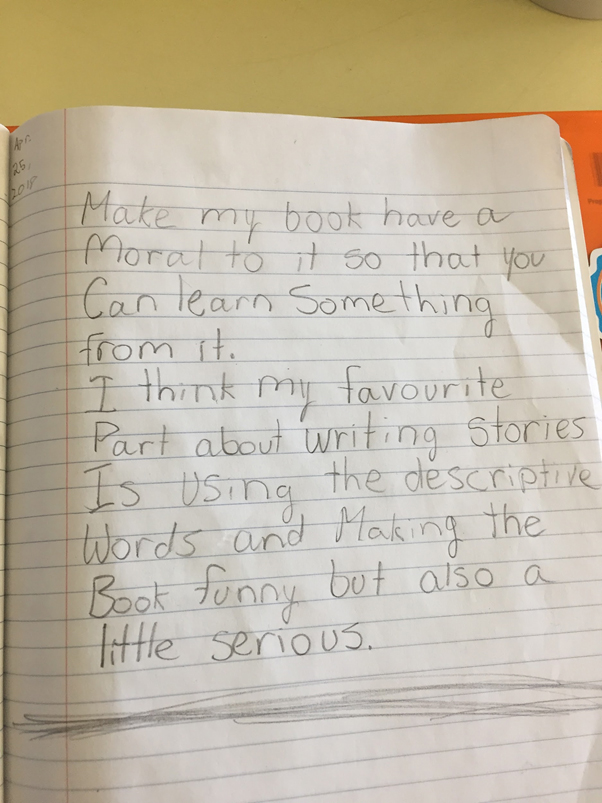

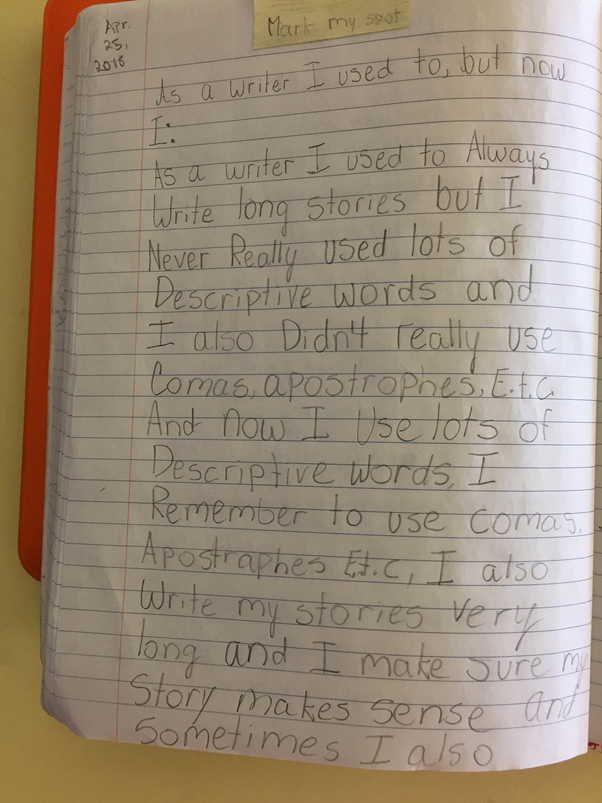

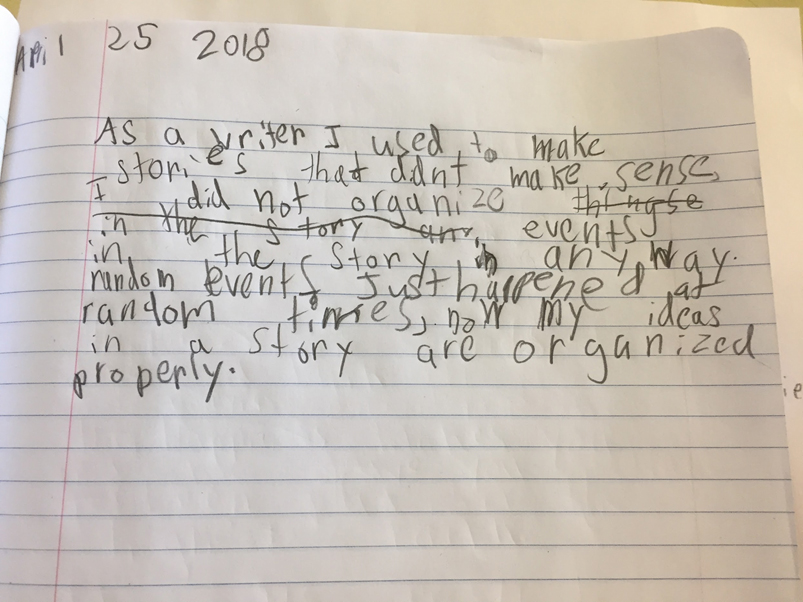

During the 2017–2018 school year, I asked my students to take a look at their writing over time and to respond to the prompt, “I used to . . . but now I. . . . ” See below for some of my students’ responses to this simple prompt, which gave me and them a new window from which to view their learning.

NCTE Standing Committee on Literacy Assessment

Peggy O’Neill, Chair

Scott Filkins

Josh Flores

Bobbie Kabuto

Becky McCraw

Kathryn Mitchell Pierce

Elisa Waingort

Kathleen Blake Yancey