This blog was written by Benji Chang, Kim Pinkerton, and Pernille Ripp, who were members of the working committee that produced the new NCTE “Students’ Right To Read” position statement in 2018.

If one stands on the precipice of a certain scratched piece of plexiglass in the Bebelplatz in Berlin, one can see the empty, white shelves which remind us that 20,000 books were destroyed there in 1933. They were enthusiastically burned by professors and students who followed a list provided to them by a librarian. How librarians, professors, and students led this travesty may be unfathomable to most, but without vigilance about the right to read — the right to read texts of our choosing — this could rather easily happen again.

It is this reality, and rather haunting reminder, that pushes the continual revision of “The Students’ Right to Read,” a position statement from NCTE. As educators, we have a responsibility to fully support this right, and that responsibility was certainly in the forefront of our minds in 2018 as we worked to reaffirm and revise this important statement.

The original statement was written in 1981 and revised in 2009. The statement was well crafted and responsive to NCTE’s stance on reading rights and the inclusion of literature reflective of people of color. It delivered background on the challenging and banning of some classic pieces of literature, elevated the importance of allowing students to read all books (no matter the challenge or ban history), assisted teachers in text selection and preparation for use of a book that may be deemed controversial, provided community members with a “Request for Reconsideration of a Text” form which prompted structure and professionalism to pending challenges, and guided teachers on how to effectively combat challenges. Those key elements of the position statement remain.

As almost a decade has passed since the last revision of this statement, we did feel that we wanted to balance the example challenges and bans from classic, secondary-level literature with some examples that include picture books, children’s literature, and contemporary young adult texts. In addition, social issues related to sexual preference and gender identity are now more commonly represented in what children and young adults read in schools, which prompted us to include additional examples.

Furthermore, we attempted to pull the central focus from only literature to include a broader definition of texts, as nonfiction texts and online sources can face the same scrutiny that could impede a student’s right to read.

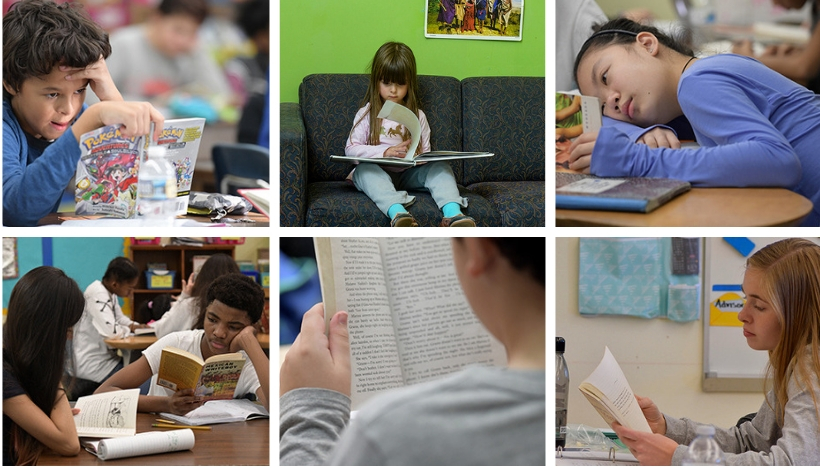

Finally, as much of the original statement pivoted on whole-class readings of texts, we felt a need to note that self-selection of texts may also draw criticism and inhibit a student’s right to choose.

Recently, teachers and librarians in the Katy Independent School District (ISD) in Texas fought to keep Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give on shelves so that students could have the choice of reading it. The best-selling young adult novel is about an African American teenage girl who witnesses the death of her friend at the hands of the police, and is moved to activism. After The Hate U Give received a parent complaint in the Katy ISD, the superintendent required the “temporary” removal of it from all shelves in the district. The book was villainized for its inappropriate language. Ultimately, the book was returned to shelves and could be checked out with parent permission.

Aside from the fact that an attempt to silence an author was made, two things are especially troubling about this story. First is that a superintendent subverted policy and “temporarily” removed the book: an educator led this charge. Second is that children can now only read it with parent permission, showing that a student’s right to read is still being stifled. And this is in 2019.

Some who faced the challenge in Katy ISD turned to “The Student’s Right To Read,” looking for guidance about how to combat the “temporary” removal. In these types of instances and related others, this NCTE position statement is still quite pertinent. It is our hope that we have added another layer of relevance and utility for NCTE members and the greater community concerned about the rights of readers within the broader contexts of educational equity and social justice.

Benjamin “Benji” Chang is an Assistant Professor at the Education University of Hong Kong. A former elementary teacher in California, his research focuses on teacher education, community engagement, and issues of language, literacy, and culture.

Kim Pinkerton is a literacy consultant who has served as a teacher educator, developmental literacy education instructor, and classroom teacher. An advocate for teachers, her research focuses on literacy lives of preservice and inservice teachers, early literacy teaching and learning, and reading comprehension.

Pernille Ripp is a seventh-grade English teacher in Oregon, Wisconsin. She is also the founder of the Global Read Aloud, as well as an author, speaker, and passionate student advocate.