An excerpt from this article by Jill Tridgell appears in the March 2019 Council Chronicle.

What do you do when faced with teaching a text centered on a controversial or sensitive topic?

Many teachers may feel a natural urge to shy away, to try to keep the conversation on safe, comfortable ground. But authors James Chisholm and Kathryn Whitmore believe this isn’t the best approach—that more thoughtful learning and deeper connections to literature can be discovered by embracing challenging texts.

Many teachers may feel a natural urge to shy away, to try to keep the conversation on safe, comfortable ground. But authors James Chisholm and Kathryn Whitmore believe this isn’t the best approach—that more thoughtful learning and deeper connections to literature can be discovered by embracing challenging texts.

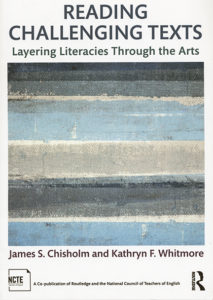

In their recent book, Reading Challenging Texts: Layering Literacies Through the Arts (NCTE, 2018), Chisholm and Whitmore combine classroom-based observations with arts-based strategies to offer practical, purposeful methods of engaging students in complex content.

The key, they argue, is to introduce challenging literature responsibly and multidimensionally so students have the opportunity to see, embody, and even feel the text.

Unique Glimpse at the Past

Chisholm and Whitmore note that preparing for emotionally charged units of study takes balance, compassion, and a keen awareness of how students are poised to handle the content. Even though there may be some reluctance from administrators or colleagues, the authors encourage teachers to embrace challenging texts when appropriate because they present a unique way to tap into history.

Tackling challenging texts admittedly takes courage, skill, and an understanding of the community—both in and out of the school. It also takes professional support, according to the authors.

“Educators need to think about local context, especially administrators and community and what you can expect,” Whitmore said. “We all need to help each other grow our own professional courage.”

Challenges Yield Rewards

Just because a topic might seem daunting doesn’t mean it should be discounted. To the contrary: being uncomfortable can be an excellent catalyst for making revelations and achieving growth. Often, challenging reads are the most rewarding because they allow for powerful intellectual connections and real-life applications of lessons learned, the authors say.

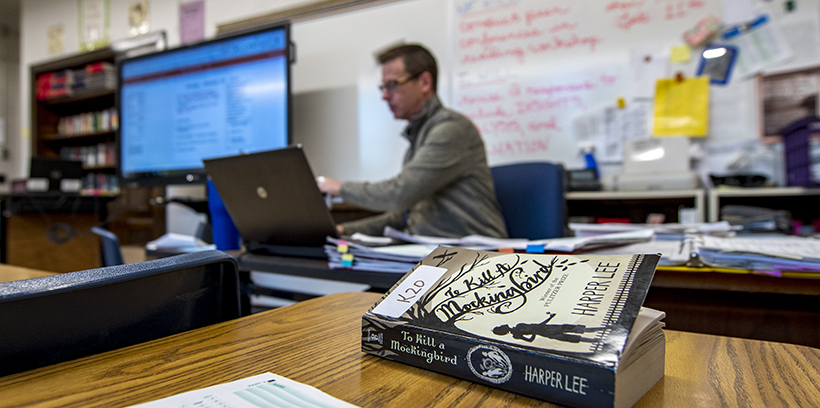

Sensitive topics can include race, immigration, LGBTQ issues, and—as highlighted in Reading Challenging Texts—the Holocaust. Central to the book is the importance of using arts-based approaches when embarking on difficult texts like The Diary of a Young Girl by Anne Frank.

Layering literacies and incorporating art, drama, and other elements can help pave the way more organically for students to come away with a truer grasp of complicated topics.

By using various tools, incorporating movement, and recognizing a wide array of learning styles, the approach of layering literacies demands that students elevate their learning to the more sophisticated parts of Bloom’s Taxonomy because of the need to analyze, evaluate, and create as they dissect complex material. Through offering accessible and practical strategies, the authors make a strong case for integrating the arts into literature lessons.

“In this book, we consider the power of the arts for teaching adolescents using challenging texts, particularly in relation to their contemporary lives,” they write.

“We show how layering the arts deepens student engagement by activating learners’ entire bodies in confronting texts that demand our attention.”

Real-Life Connections

Through these strategies, students glean lessons and relate them to their own lives and behaviors, according to Fred Whittaker, a science and religion teacher of Holocaust studies at a Catholic school in Louisville, Kentucky.

“We are not trying to make only historians here. We are trying to create community makers,” says Whittaker, who teaches his semester-long course to eighth graders and is featured prominently in Chisholm and Whitmore’s book.

“At the end of the day, what we hope to do is place them on a trajectory to really have a sense of their own morality and ethics.”

Rest assured: teachers need not be authorities on any one topic in order to teach it. However, preparing for units centered on challenging texts takes thought and preparation, as well as a willingness to let go of the reins and learn from students at times.

“Position yourself as teachers as learners,” Whittaker said. “Make yourself vulnerable so students know it’s OK to take risks and try new things” in the classroom.

Strong Classroom Community

But in order to do any of this with measurable success, perhaps the most important part comes early on in establishing a respectful classroom community, according to the book. Teacher Fred Whittaker subscribes to this wholeheartedly.

“We need to respect and dignify each other’s beliefs . . . in a way that’s safe,” Whittaker says.

Chisholm and Whitmore agree: confronting some of these more controversial or unsettling realities takes respect, compassion, and a willingness to feel what others felt at important times in history—and even present day. Because, naturally, parallels are often found. Photographs are a particularly powerful tool that connects today’s students to some indelible moments in time.

The authors caution, though, that educators should refrain from inundating students with especially devastating images—particularly at the start of a unit. Both the images and the students must be tended to with care.

“How do you get people to feel something without sensationalizing those people and what they went through?” is a question Whitmore says teachers need to keep in mind when presenting photographs.

Power of Imagery

Introducing powerful imagery that pertains to challenging topics should be well thought out. Chisholm and Whitmore offer several suggestions for how to go about implementing visual literacies.

One strategy is “cordel”—otherwise known as “string literature.” Here, visual and linguistic texts pertaining to a topic hang from a string across the room, beckoning students to interact with photographs, poems, stories, maps, and more.

Jacqueline Epler, a fourth-grade ILA and social studies teacher at Bragg School in Chester, New Jersey, read Reading Challenging Texts as part of the NCTE Reads summer book club and took away some profound strategies.

“After reading about cordels, I felt they would create a different immersion experience for my students in reading and writing,” Epler said.

“By viewing photos of the lives of immigrants traveling through Ellis Island, students made a deeper connection to this topic than I’ve ever experienced in all the years I’ve taught this unit. The historical fiction stories they crafted were filled with voice and pulled their readers into the minds of immigrants during this time period. Incorporating a cordel truly transformed the writing experience in my classroom.”

Another visual instructional strategy noted in the book is “icons,” in which a subject is broken down into a list of words. Then students select one of those word to create a visual aid, using only paper and scissors. Turning these interpretations of the text into visual icons helps learners make concepts concrete and tangible, according to the authors.

A third approach is using “archives” taps into the power of abduction—jumping to conclusions based primarily on first reactions and intuitions.

Honor the Memories

But whether incorporating photos or another tool, it is imperative that teachers present all sides of a story or issue—even the unseemly ones.

“It is important to honor the complexity of the resisters, the perpetrators, the bystanders,” Chisholm notes.

Whitmore adds: “We pull back history’s curtains to expose [students] to humanity at its very worst . . . so they cannot just stand in awe of how dangerous people can be, but to provide them with an understanding of the power and responsibility they have to counteract (actions like this) with their own acts of kindness and mercy. We want them to walk out with courage and not fear.”

Jill Tridgell is a freelance writer with 20 years of journalism experience in newspapers, magazines, and book editing in suburban Chicago. She taught middle school language arts for several years after receiving her teacher certification in urban education.