This blog post is part of Build Your Stack,® a new initiative focused exclusively on helping teachers build their book knowledge and their classroom libraries. It was written by NCTE member Alie Stumpf.

The journey to my “stack” begins in my homogeneously White, rural New England hometown, where people assumed similarities and fought to keep the status quo.

We mostly read the British and American canon for class, and I feasted on Lois Duncan and R. L. Stine’s Fear Street series on the side. I had just one memorable teacher of color, an elderly Black woman who introduced me to Night and horrors of the Holocaust, but not to Morrison, Baldwin, or Angelou. Eventually in high school we read Things Fall Apart and Raisin in the Sun, yet without critically analyzing the effects of imperialism or redlining that drive the works. As a result, our conversations about Okonkwo and Walter focused on tragic flaws rather than the crushing impact of White supremacy.

In essence, until I went to college, I was not challenged by my curriculum or my community to consider the ways social policy or privilege impact a person’s life. I read books about lives different from my own, but without important context, I judged characters through my own world view and privileges. I began to realize all I had missed, rushed to catch up, and got the urge to teach.

Early on in my own teaching career in NYC, I learned of Rudine Sims Bishop’s work, advocating that books offer children mirrors to see themselves in, windows to see into others’ lives, and sliding glass doors to walk into worlds different from their own. I culled library books that embraced Dr. Bishop’s vision; from Jacqueline Woodson to Matt de la Peña, I figured where some found mirrors, others would find windows, and the interaction would breed curiosity and compassion.

Throughout various schools and grade levels, I found a similar, unsettling trend; kids often struggled to read honestly for windows into others’ lives. Regardless of reading skill or age, kids either breezed through or abandoned books that challenged them to learn unfamiliar names, places, or historical events. (I’ve found fantasy readers to be a big exception to this; most will memorize cat clans and magical worlds as a way of clinging to the certainty of the good/evil trope.) A sixth-grade student read Rita Williams Garcia’s One Crazy Summer in just a few days, remarking that she loved the book and could not understand why the mom was so mean. I asked her what she had learned about the Black Panther Party and she stared at me, blankly. Another student clung to the detail that Jason Reynold’s protagonist Castle Crenshaw was being raised by a single mom, yet overlooked the ways the trauma of domestic violence lingered.

Similar to the way I was reading as a kid, my students either subconsciously or intentionally skipped over the parts of the book in which the character experienced something for which they themselves had no point of reference, rendering an incomplete perception of a character or misunderstanding the complexities of a culture or historical event.

Of course, I had provided such information for students when reading whole class novels, yet I yearned for a structure that placed the responsibility more on the student. If I wanted my students to read their independent choice books for windows, then I needed to give them tools and time to conduct research that their books inspired.

Discovering Jess Lifshitz on Twitter changed all of this for me. In her incredible blog Crawling Out of the Classroom, she details ways that she teaches readers how to read for windows. She honors her students’ proclivity toward mirrors while priming them to linger on differences. While reading for windows, her students:

- see themselves reflected in the lives of others who are different

- learn something new about the world or the people living in it

- form questions when they need more information in order to understand the characters experiences

This framing allows students to go beyond simple connections and use reading to expand their understanding of humanity. It also stresses the importance of using a novel to inspire nonfiction research, of giving students opportunities to move between books and online sources to grow their understanding of an unfamiliar setting.

We have been reading both in clubs and individually throughout the semester, making space for questioning, reflecting, and online research along the way. This year students still leaned on me for resources to find answers to their questions, yet I hope to grow their research skills earlier next year so that they can develop greater independence.

The following are some of the books and nonfiction resources that moved students:

Ghostboys by Jewel Parker Rhodes

Many students read in book clubs, and none of them had a solid idea of who Emmett Till was. They watched a Time video “The Body of Emmet Till” narrated by Bryan Stevenson. Carving out class time to watch this film together and conduct supplemental research allowed them to experience the shattering images of Till’s funeral, learn the role such photography played in galvanizing the civil rights movement, and make connections to the media-driven Black Lives Matter movement.

It Ain’t So Awful, Falafel by Firoozeh Dumas

Set in the 1970s, Iranian refugee Zomorod tells the story of how she and her parents struggled to settle and find work and community in the US. The family angrily witnesses the Iranian revolution from the television, and must face a surge in anti-Iranian prejudice in their community. The kid-friendly encyclopedia website Ducksters has some helpful information about the Iran Hostage crisis, which Zomorod and her family agonize over for much of the book. Zomorod’s witty narration and changing friendships also make this an enticing read for middle schoolers.

Amina’s Voice by Hena Khan

If you have been seeing this book everywhere, It’s for a good reason. Get it! One of my students read it for Gene Luen Yang’s Reading Without Walls challenge, and struggled to get past the “girl drama” in the beginning. Once we read about the Islam faith and about the process of becoming a US citizen, as Amina’s friend Soojin experiences, he began to see the book as more meaningful. Shortly after he finished the book, the Christchurch massacre in New Zealand occurred and he was both amazed to see events from the book playing out in a larger, more deadly scale, and also disturbed by such deep, senseless misunderstandings.

Save Me a Seat by Sarah Weeks & Gita Varadarajan

With its alternating perspectives, this novel is interesting (and confusing for some), because Joe and Ravi do not develop a relationship with one another until pretty late in the novel. While Joe struggles with an auditory processing disorder and a history with the school bully, Ravi, a recent immigrant from India, struggles to find his place among his teachers and peers in a new setting. My co-teacher used Google images to give students a virtual tour of large classroom settings in India, helping students process why Ravi is so eager to stand out and get the teacher’s approval in class. This “windows” work shifted some students in their analysis of Ravi; they better understood his need for attention and were less apt to label him “annoying.”

Fish in a Tree by Lynda Mullaly Hunt

Ally Nickerson’s life revolves around her fear that people will discover her most tightly held secret—she can’t read. Her secret not only keeps her on edge, but also distances her from other kids and adults who might help her. Ally eventually confides in a teacher, who helps her learn about her dyslexia and discover her true intellect. A few years ago at the NCTE Convention, I heard Hunt speak about her own learning challenges and the transformational influence a teacher had on how she thought about herself. Many of my students have learning challenges, and it’s helpful to give them mirrors and windows into the challenges they or their peers face. I recommend the site kidshealth.org to research specific conditions in kid-friendly terms.

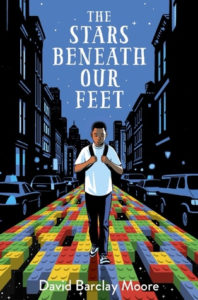

The Stars Beneath Our Feet by David Barclay Moore

My students have been enthralled by Lolly’s Lego creations and impressed by his navigation of a violent landscape. One student misinterpreted Rose, characterizing her as cold and unfeeling because she did not seem to react to anything—even her own mom dying. It took some research about the autism spectrum for him to better understand this character. In addition, the Everytown For Gun Safety’s website captures local data about gun violence, giving kids a visceral snapshot of the severity of the problem and about which communities it impacts the most.

We are still trying to find the balance in my classroom between trusting that the author will explain and looking up historical or setting details to engage more deeply with the text.

My “next steps” in this work include finding more nonfiction picture books to make it easy for kids to find the right book during independent reading. I also need to remind myself that kids need the support to reach beyond what’s comfortable and the same freedom to abandon books that aren’t working for them. Some authentic #ownvoices work so rawly immerses readers in their cultural world that it can feel disorienting or overly intimate, yet other readers may find the same authenticity illuminating or validating. What remains crucial is connecting kids with helpful resources that demystify “windows,” and invite them to become more responsible readers of the world.

Alie Stumpf has been teaching reading and writing in New York City public schools since 2006. She lives in Brooklyn and currently teaches sixth-grade humanities in Manhattan.