This blog post by NCTE member Frank Baker appeared originally on MiddleWeb on 1/26/2021, and is reprinted with permission.

The inability of many of today’s students to evaluate information online for truthfulness has become a crisis in American education.

Even though most students now use the Internet as their primary tool to learn what’s happening in the world, the education system has been slow to acknowledge the problem and begin a serious search for solutions.

I hope you’re ready to do your part, and that you’ll find what I’ve shared here useful in shaping a better educator response to a global trend that Oxford researchers describe as “industrialized disinformation” and the Rand Corporation calls “the era of Truth Decay.”

Some Facts You Need to Know

In 2016 researchers at Stanford University’s History Education Group (SHEG) labeled students’ lack of critical thinking about information they find on the web as “dismal.” (A more recent study found college age students similarly deficient.)

Since the release of the Stanford report four years ago, “policymakers and educators have introduced a wave of initiatives aimed at equipping students with stronger digital literacy skills,” an October press release from Stanford noted. “But as the 2020 election approaches and many of those students become first-time voters, SHEG researchers have found few signs of progress” in the intervening years. (Source)

SHEG cofounder Sam Wineburg lamented the failure as “a threat to democracy.” He urged policymakers and educators to focus on and fund effective ways to teach students how they can separate truth from fiction in digital media:

We’re still very much seeing students struggle to make sense of the information they encounter. In 2019 we released the most extensive study to date on how young people go about trying to verify a claim on social media or the internet, based on research with more than 3,000 high school students matching the demographic profile of students across the United States.

More than half of the students believed that a grainy video on Facebook of ballot stuffing provided “strong evidence” of voter fraud during the 2016 US primaries, even though the clips were actually shot in Russia. More than 96 percent failed to recognize that a climate change denial group was connected to the fossil fuel industry.

These are claims that are easily discernible in two or three steps on the internet. So sadly, no—young people’s ability to separate fact from fiction hasn’t improved in the last four years.

In early 2020, the Rand Corporation released a major report “Media Use and Literacy in Schools—Civic Development in the Era of Truth Decay.” Its key details and recommendations have important ramifications for current and future instruction in schools.

One major finding of the “Truth Decay” report:

. . . nearly 80 percent (of the secondary teachers surveyed) described (their students’) “limited ability to evaluate the credibility of online information” as a moderate or major problem. 92 percent of the teachers said “students must learn to critically evaluate information for credibility and bias—it’s a crucial citizenship skill.” (Source)

Some science teachers have reported that students trust YouTube videos more than the instruction they receive in class. It appears students often believe misinformation about climate change, the flat Earth, and vaccine safety, and may challenge conventional science facts. The Rand report seems to confirm that—finding that teachers reported “students have made unfounded claims in class based on unreliable media sources.”

Just this week, three researchers at the Oxford University Internet Institute (OII) a report, Industrialized Disinformation, that found “evidence of organized social media manipulation campaigns in all 81 countries surveyed in 2020, a 15% increase.” The report speaks of “cyber-troops” which it defines as

“. . . social media accounts that spread doctored images, use data-driven strategies to target specific sections of the population, troll political opponents, and mass-report opponents’ content so that it is reported as spam. These accounts can be either automated or human.

Facebook and Twitter revealed that they removed more than 317,000 accounts and pages from their platforms in a 22-month period (Jan 2019 to Nov 2020), but they are up against an industry that has become “professionalized, with private firms offering disinformation-for-hire services,” says Dr Samantha Bradshaw, a researcher at the OII.”

Do our K12 students realize they live in a social media-soaked world where battles like these are going in the background of their daily digital lives? Would you agree that we have a responsibility to help them understand the breadth and depth of the problem and how they can respond effectively?

Some Education Context

Concerns about online misinformation have a long history among educators. In 1998, in the early days of the internet, education technologist Alan November presciently noted that not enough educators were dedicating instructional time to teaching students how to deconstruct the new World Wide Web. His now-classic essay “Teaching Zach To Think” is a must-read for every educator. (As you read it, ask yourself if much has changed in 22 years.)

More recently, the educational challenge has been framed as “internet literacy.” In May 2009, the International Reading Association published “New Literacies and 21st Century Technologies”—landmark report (PDF) that expanded on the concept of literacy and urged educators to recognize the need to embrace “new literacy” education.

Yet, when they were published in 2010, the influential Common Core ELA standards made only one substantive reference to the need for students to be smarter about online information. College and career-ready students were expected to “gather relevant information from multiple print and digital sources, assess the credibility and accuracy of each source and integrate the information while avoiding plagiarism.”

“At the top level, they’re saying, yes, we recognize literacy means being digitally literate,” said Bridget Dalton, an associate professor of literacy studies at the University of Colorado at Boulder. “But when you go to specific standards in reading, there’s not a lot there to guide you.” (Source)

Dr. Donald Leu, Director of the New Literacies Research Lab at the University of Connecticut, agrees that schools are “the key to solving the fake news problem.” Yet, he noted in 2016, teachers have not been trained adequately nor do they have sufficient resources to fully address this 21st century literacy challenge. “If I were going to invest in one thing, that’s where I would invest—giving teachers the instructional tools they can use to teach kids to think critically about online information.” (Source)

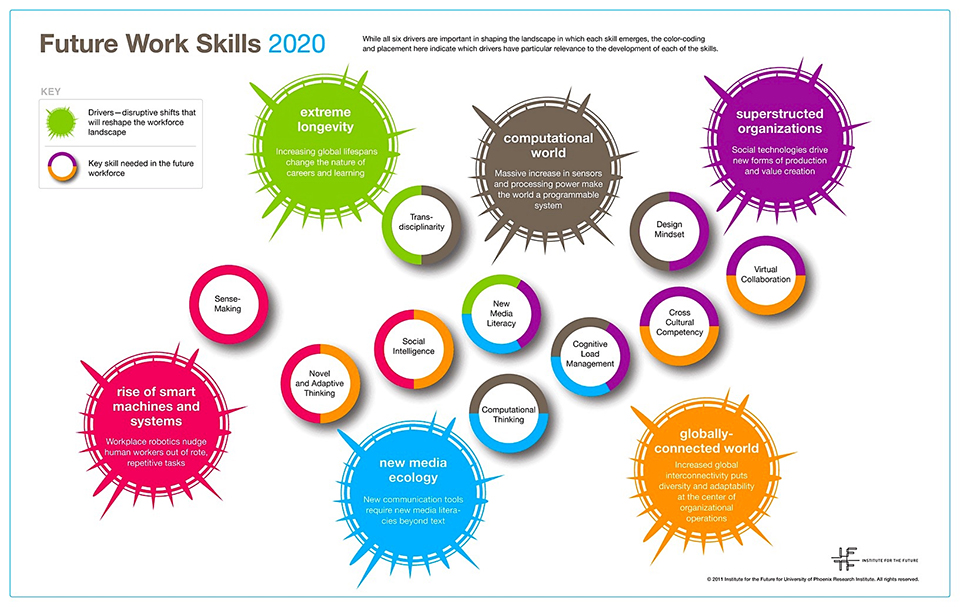

Educators will find more guidance, from a standards perspective, in The Future Work Skills 2020 report which recognizes the “New Media Ecology” we live in and recommends the key skills students need. The New Media Ecology demands that educators acknowledge the “new communication tools require new media literacies beyond text.”

Starting Down the Path to Media Literacy

How do we help students become better thinkers about everything they consume? One answer is “media literacy,” which provides learners with the critical thinking skills to analyze, question and create media messages. Understanding how to identify credible sources is a critical skill and an important step toward full digital citizenship.

To evaluate information, students need to consider several factors: Author; Currency; Accuracy; Purpose; and Audience. I recommend that you introduce your students to each of the concepts and these questions they need to consider when evaluating information. (Source)

Author:

- Is the author qualified to write on this topic?

- Does the author have affiliations with reputable institutions?

- Does the author cite other sources in a reference list?

- For websites such as YouTube, is it clear who is posting the content?

Currency:

- Is the information up to date for your purpose?

- Is the website content current for your purpose?

- Check the publication date for all content

Accuracy:

- Is the information factual and correct?

- Is a reference list or bibliography included?

- Can the information be confirmed by research, statistics or studies?

Purpose:

- Does the author provide a particular perspective (e.g. political, historical, gendered, or religious)?

- Are multiple viewpoints presented?

- Are the author’s conclusions based on personal opinion or evidence?

Audience:

- Who is the information for: the general public, scholars or professional practitioners?

- Is this reflected in the writing style and terminology?

As you begin to help students become better critical thinkers, you may wish to consider printing these factors and questions as a handout or making a poster for your classroom.

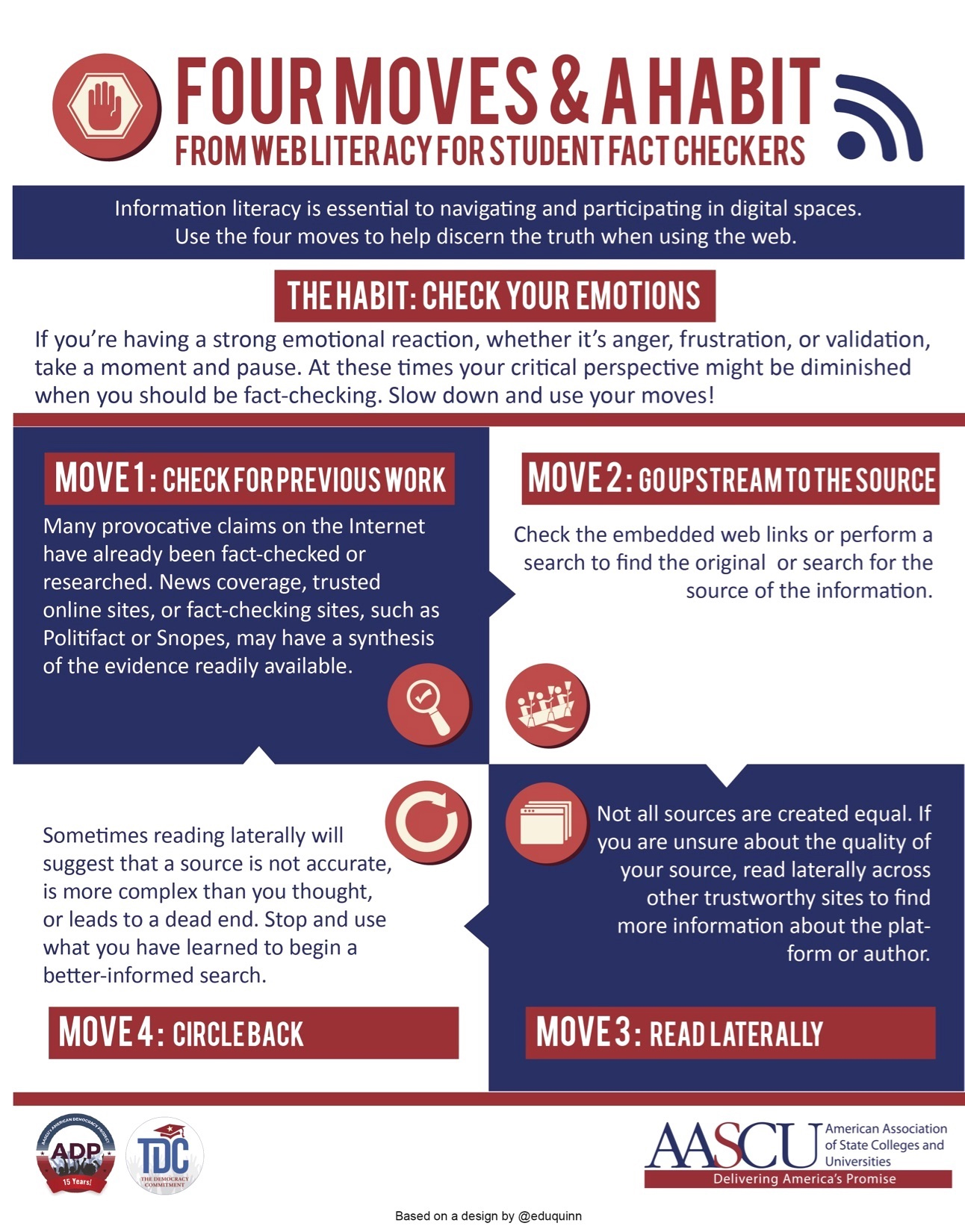

Some experts are suggesting that this type of evaluation may be insufficient or outdated. Instead they recommend Mike Caufield’s SIFT model: STOP, INVESTIGATE, FIND and TRACE, which includes “Four Moves and a Habit.” Read how to incorporate “the Four Moves” here.

Many education organizations are already on record urging schools to teach digital literacy and digital citizenship, and several now offer curricula. See the Recommended Resources at the end of this post. ISTE—the International Society of Technology in Education—has long promoted digital citizenship and teaching standards and offers educators guidance.

Why Aren’t Students Better at Doing This?

Although I could not locate any current research that fully answers this question, I have some ideas. I believe that today’s students have weak media and information literacy skills because:

- Teachers have had little, if any, professional development in how to teach media literacy, so they don’t.

- The ELA teaching standards may reference critical thinking about web content, but this standard is often not a priority and also not a part of every discipline’s standards.

- Some educators have the mindset: “It isn’t part of what I’m responsible for teaching.”

- Librarians have a role as teachers of “information literacy,” but some may not be keeping up with the times, which include widespread intentional efforts to deceive.

- Colleges of education don’t offer courses so new teachers don’t get instruction.

- The existing “digital literacy” curriculum is insufficient and/or ineffective.

- Parents, who may not monitor their student’s online habits, don’t recognize the weaknesses in their child’s critical thinking skills or know how to address them.

Do any of these ring true in your experience?

In a recent webinar I hosted, one teacher offered this reason: she said her students are part of a generation that wants things fast, so they hurry and don’t bother to verify because it would take too long. Does this sound familiar? If so, what strategies might encourage them to slow down and engage?

A Call to Action

So now that we know what the problem is, what are some things we can do? In general, state and local boards of education, state departments of education, and district-level leaders in every state must make media and information literacy a much higher priority.

Only when these literacies are identified as “must do” and appropriately assessed will teachers receive the time, training and continuing support to become media literacy educators. If federal elections and Constitutional principles are at stake, it makes sense for Congress and the executive branch to provide funding to rally educators around this goal.

At the school and district level, my colleague Chris Sperry of Project Look Sharp recommends an integrated approach that has teachers from all disciplines and grade levels engage their students in the practice of asking key questions for media analysis as part of content area instruction.

Through constructivist media decoding (Project Look Sharp’s approach), educators can teach both core subject area knowledge and media literacy habits. “If teachers use this engaging methodology across the curriculum,” says Sperry, “our students will be better prepared to manage current and future epistemological threats to our democracy.

Consult Your School Media Specialist

If we need to add another “hero” to our growing list in this new decade, I nominate the nation’s school librarians. They are the “go to” educators for teaching the so-called “digital natives” how to not only use the Internet, but also how to think critically about that use at the same time. If you’re fortunate enough to have a teacher specialist in that role in your school—and you have not yet collaborated to help your students get “up to speed” on verification skills—now would be a good time.

Conclusion

Do you feel prepared or overwhelmed? Where will you go for advice and assistance? How will you proceed? I hope this post offers you some ideas and direction. Providing opportunities for our students to be engaged in critical thinking about online content is not only important, but urgent in these times of social and political unrest and uncertainty.

What action will you take? Only you can prevent media illiteracy.

Recommended Resources

► From my perspective, it is clear that many students are not taking the time to verify what they consume. Verification skills should become a priority. If you missed my previous post, Verification: It’s The Number One Vocabulary Word of 2020, now might be a good time to read it.

► Another MiddleWeb post, Helping Our Students Identify as Generalists, also explores the idea that even when students understand the basics of fact-checking and information-mining, they still need to be motivated to use their skills.

► Project Look Sharp provides over 500 free lessons for this work, searchable by keyword, subject, level or standard, as well as video demonstrations for leading media decoding activities (online and in person).

► The Rand Corporation has recently followed up its “Truth Decay” study with recommendations for media literacy standards for schools.

► The In-School Push to Fight Misinformation from the Outside World (Hechinger Report, 2021)

► Everything You Need to Teach Digital Citizenship (Common Sense Media, 2019)

► Be Internet Awesome (Google game and resources)

► The Media Education Lab at University of Rhode Island offers insights and free curriculum materials addressing media literacy and propaganda.

► Civix News Literacy/Canada Helping Students Fight Information Pollution

► Why Can’t a Generation That Grew Up Online Spot the Misinformation In Front of Them? (Los Angeles Times op-ed – Sam Wineberg & Nadav Ziv. 11/6/20)

► Create to Learn: Introduction to Digital Literacy by Renee Hobbs (Wiley Blackwell, 2017)

► Why Learn History (When It’s Already On Your Phone) by Sam Wineberg (University of Chicago Press, 2018)

► Sharpen Your Critical Thinking: Five Simple Strategies (A BBC Ideas Video)

► Media Literacy Starts with SEARCHing the Internet (ISTE Blog – Jodi Pilgrim and Elda E. Martinez – 10/23/20)

► Teaching Adolescents How to Evaluate the Quality of Online Information (Julie Coiro, Edutopia, updated 8/29/17).

► Evaluating Sources in a ‘Post-Truth’ World: Ideas for Teaching and Learning About Fake News (New York Times Learning Network)

► “Misinformation in the Information Age: What Teachers Can Do to Support Students.” (Social Education, NCSS, Joe Kahne and Erica Hodgin (2018).

► “Rx for an Infodemic: Media Decoding, COVID-19 and Online Teaching.” (Social Education, NCSS, Chris Sperry and Cyndy Scheibe (2020).

Frank W. Baker conducts professional development workshops both face-to-face and via webinar and virtual workshops. His most recent book Close Reading The Media was praised as “an incredible resource for any middle or high school humanities teachers looking to teach students how to think critically about the media they regularly consume.” Follow him on Twitter @fbaker

Frank W. Baker conducts professional development workshops both face-to-face and via webinar and virtual workshops. His most recent book Close Reading The Media was praised as “an incredible resource for any middle or high school humanities teachers looking to teach students how to think critically about the media they regularly consume.” Follow him on Twitter @fbaker

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.