This post was written by Ann D. David and Katharine Covino, members of the NCTE Standing Committee Against Censorship.

At the NCTE Homecoming Conference in Louisville this summer, I was privileged to share the stage with two of NCTE’s partners: Jeremy Young from PEN America and Jennifer Warner from STAND for Children. While I have been a member of the Standing Committee Against Censorship for four years, they offered insight into this moment of book challenges and bans that helped me reframe my understandings in important ways.

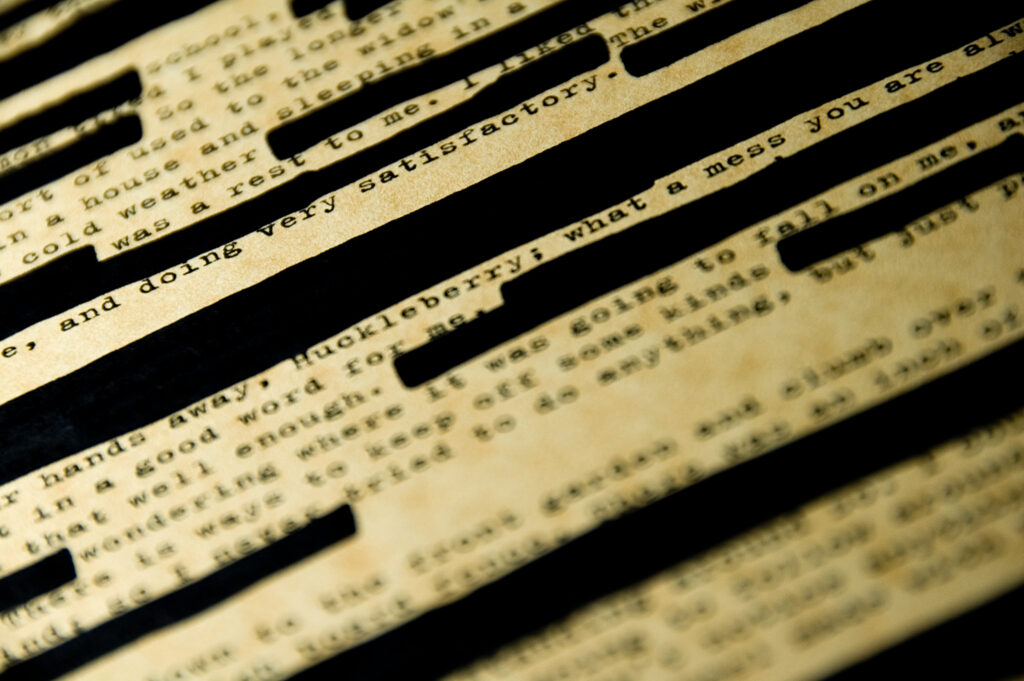

First, Jeremy outlined the educational gag orders that have been proposed and passed in many states. These are bills that include bans on divisive concepts and the division or classification of students. Often referred to in the media as “anti-CRT” bills, PEN America argues instead that “these bills appear designed to chill academic and educational discussions and impose government dictates on teaching and learning. In short: They are educational gag orders.” (PEN America Report). These bills, which continue to make their way through various state legislatures (tracking list), create this climate of fear around education discussion because they are vague and open to interpretation.

Listening to Jeremy explain the political nature of these bills was comforting. It was comforting, because I remember being a high school English teacher and working hard to avoid being “political” in my English class in the early 2000’s, when politics were not nearly as rancorous. But when I talk to the preservice teachers in my university classroom, they want to understand the ways that schools and teachers are being drawn into partisan politics, because they see this reality on the news and they hear teachers talk about it. I too follow the news closely, but until recently had been hedging around the political nature of these challenges and bans. Jeremy, though—with his data and research and careful presentation of the facts—helped me name what I had been feeling as political. The reports PEN America has written also codify the scope and scale of these pressures on teachers and schools, which is different than anything our society has experienced previously.

Second, Jennifer offered her perspective as a long-time community organizer, specifically the importance of having one-on-one conversations with people in the community to help them become more actively involved in advocating for intellectual freedom. She talked about the power of teachers sharing their stories with parents and community members as a way of personalizing these political forces at work. Her suggestions reminded me of the resources in Everyday Advocacy, which include practical tips for community organizing in your school and community.

During the question-and-answer period, a teacher explained that she and her colleagues had been successful in retaining a book that had been challenged in her school. She asked the panel, “How do we make sure a challenge like this doesn’t happen again?” And, much like Jeremy’s talk, Jennifer’s answer has stayed with me for its clarity: “You can’t. Because the challenges are about making a spectacle, about taking energy away from other things, about being distracting. So your goal can’t be to prevent a challenge.” When Jennifer answered this way, it caught the room off guard, because it is unusual to have a speaker tell you that you can’t do something. But her honesty in that moment also was revelatory. Often these challenges are not about making schools better for kids, but about creating a political and media spectacle that distracts from all kinds of other issues.

What I’m carrying with me from these conversations as I continue into the fall is that what teachers are feeling is real: book challenges, and bans, and laws restricting what and how topics can be taught make our work harder. What I’m also carrying is the spirit of teachers who do the work to keep books in their classrooms and curriculum. Knowing the work is hard and not what they signed on for, they do it for their community and their students, who grow as readers by reading stories that matter to them. They do it for democracy.

As a last point, I’ll also remind everyone reading that NCTE’s Intellectual Freedom Center offers support for teachers facing challenges. Censorship can also be reported to the National Coalition Against Censorship. Book challenges happen, so being prepared can blunt their force, and drawing strength from your teacher colleagues makes it possible to continue the work of teaching in the midst of our current world.

Ann D. David, associate professor at the University of the Incarnate Word, is a teacher educator, codirector of the San Antonio Writing Project, and a member of the Standing Committee Against Censorship. She has also taught English and theatre in high schools in the midwest. Her scholarship focuses on writing and the teaching of writing, as well as the impacts of censorship on English language arts teachers.

Ann D. David, associate professor at the University of the Incarnate Word, is a teacher educator, codirector of the San Antonio Writing Project, and a member of the Standing Committee Against Censorship. She has also taught English and theatre in high schools in the midwest. Her scholarship focuses on writing and the teaching of writing, as well as the impacts of censorship on English language arts teachers.

Katharine Covino, associate professor of English Studies, teaches writing, literature, and teacher-preparation classes at Fitchburg State University. Current scholarship explores critical pedagogy, applying indigenous lenses to cultural myths, and action research with English teachers. Before university teaching, she taught middle school and high school. She is also a children’s book author: You Got a Phone! (Now Read This Book) uses humor and science to help kids use (and not abuse) smart phones.

Katharine Covino, associate professor of English Studies, teaches writing, literature, and teacher-preparation classes at Fitchburg State University. Current scholarship explores critical pedagogy, applying indigenous lenses to cultural myths, and action research with English teachers. Before university teaching, she taught middle school and high school. She is also a children’s book author: You Got a Phone! (Now Read This Book) uses humor and science to help kids use (and not abuse) smart phones.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.