This post was written by NCTE member Sarah Elizabeth Smith Carter.

As English and ELA teachers prepare for the National Day on Writing, I invite educators to present the opportunity to encourage students to spend some time reflecting on their personal literacy journey. It is not very often that we ask our students, K–12 and in higher education, to reflect on their experiences with reading and writing. Many students are just moving through the system, day in and day out, never considering what choices they have made to get to the present moment in time, what challenges they have faced, what role others have played in their literacy, and what will come next. As many scholars have noted, “the journeys we take as literate people cannot be told in a single story from a lone perspective; rather, these journeys unfold through a series of experiences and events that occur over time and are influenced and changed by the perspectives and actions of those around us” (Hope et al. 2022).

Scholars and teachers for many years have promoted the inclusion of literacy narratives in primary, secondary, and higher education classrooms for a variety of reasons. Bronwyn Williams notes in the article “Heroes, Rebels, and Victims, Student Identities in Literacy Narratives,” “I am a fervent advocate of literacy narratives and assign them in almost all the courses I teach at every level. The form and the focus are sometimes different, depending on the course, but I never regret making the assignment and never fail to find it as fascinating a learning experience for me as it is for my students.”

There are several resources that can help teachers and students complete a literacy narrative activity. One wonderful resource is the Digital Archive of Literacy Narratives (DALN). Established in 2007, the DALN is an excellent resource to help instructors introduce both literacy narratives and archives as a form of research and investigation. The site is incredibly user-friendly, and students can familiarize themselves with how to perform a successful search by learning to identify keywords and phrases.

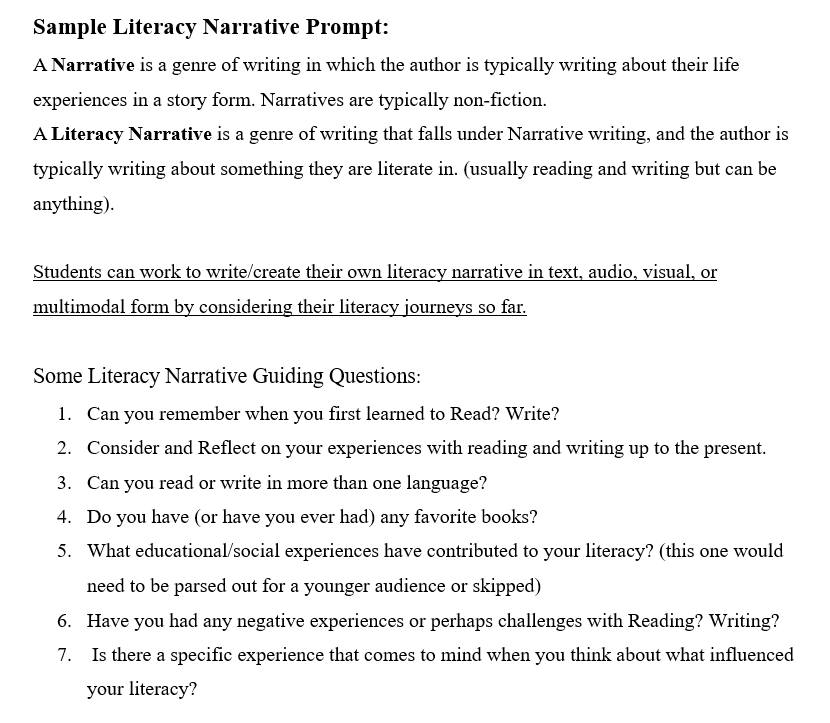

Introducing varying forms of creation for literacy narratives (written, audio, visual, multimodal) allows a larger range of comfort for students of all ages. Additionally, presenting the literacy narrative as a low-stakes assignment that can be graded as complete vs. incomplete without grading for grammar and traditional conventions of standardized writing can increase student confidence in their work and promote identity. Literacy narratives can benefit students from all backgrounds, cultures, and communities—as a study in South Africa points out, “literacy narratives can serve as an outlet for reconstructing experiences of social injustice and agency” (Angu 2018).

So I invite you to try something new on October 20th. Encourage your students to write/create a literacy narrative, and encourage them to share, because “most importantly, we must become students of our students’ literacies, for in learning from one another and from our students, we may avoid harm” (Hourigan 1994).

Sarah E. S. Carter is the Director of First-Year Composition at Clemson University. She loves teaching and helping students succeed within and beyond academia into their professional lives.

It is the policy of NCTE in all publications, including the Literacy & NCTE blog, to provide a forum for the open discussion of ideas concerning the content and the teaching of English and the language arts. Publicity accorded to any particular point of view does not imply endorsement by the Executive Committee, the Board of Directors, the staff, or the membership at large, except in announcements of policy, where such endorsement is clearly specified.