This was written by member R. Joseph Rodríguez.

November 16, 2009, 14:28 EST, I am watching from my television, live—anxious, excited—as Atlantis prepares for liftoff with many scientists and engineers working together on a special mission. Leland Melvin, an engineer and NASA astronaut, is aboard. I will meet him eight years later at the NCTE Annual Convention in St. Louis, Missouri.

Human exploration requires the sciences and language arts to communicate the wonder of our universe in order to foster imagination and innovation. This extends to teaching and research across the arts, humanities, and sciences.

Emerging Science Knowledge

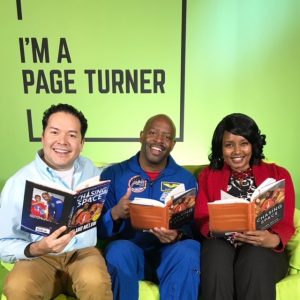

As an attendee of the 2017 NCTE Annual Convention, I met astronaut Leland Melvin. His commitment to literacy in the sciences, arts, and humanities reminds me how interconnected and interdependent we are as educators across the disciplines.

My interests in the sciences can be traced to NASA’s Mission Control Center in Houston, TX, where I was born and raised. My parents and siblings visited the Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center and learned about human space exploration through exhibits, simulations, and tours. With my burgeoning science knowledge, earth science and deep space technologies captivated me.

On a sunny Tuesday morning, January 28, 1986, my fifth-grade classmates and I had just left physical education class. Our teacher, Ms. Sammie Wiggins, met us and then led us to our classroom on the second floor of Benjamin Franklin Elementary School.

After we sat down, she looked at us more intently and paused . . . then shared the news that the NASA space shuttle Challenger (STS-51-L) had exploded, killing seven astronauts, including Christa McAuliffe, the first teacher going to space.

An exciting lesson about the sciences and a teacher traveling beyond our planet was altered.

But our curiosity was sparked as we asked more questions, like the emerging young scientists we were. I had my arm up, eager to know more, waving to be recognized.

When I was called, I was half-seated, half-standing and asked, “Why did this happen? Are they going to investigate this? What’s going to happen next?” Ms. Wiggins explained we would learn more in the months ahead.

To Challenge

Thirty-one years later this memory is still as vivid for me as if it were this year. My reflection is strengthened in the classroom, as I remember my teacher’s coaching and motivation in the face of difficulty—then and now.

“Every student can learn” was Ms. Wiggins’s mantra. When I entered her classroom during the fall of 1985, I knew some challenges awaited. My brother had been her student the previous year, so I braced myself for intense learning.

I would watch him solving math problems and reading and rereading at the dinner table during the late evenings, when I preferred he join me and play marbles outside or race with our Matchbox cars.

In the book Because Teaching Matters (2009), Marleen C. Pugach explains, “For some students, a teacher is remembered as someone who turned their lives around completely. Whatever the situation, the influence teachers have on their students is long lasting and frequently it is profound” (1).

“How are you doing, students?” Ms. Wiggins would ask in the early mornings, with sincere interest, as we stumbled into our seats from our working-class neighborhood and our lives there. Here, in her classroom, learning happened despite the push and pull of our everyday lives. We mattered; learning mattered.

Like Ms. Wiggins, most of my public school teachers were African American women. Although they were neither working class nor spoke Spanish, I admired them for what they knew and said, and the smiles they offered us were warm and inviting.

I still remember running with a few classmates in our worn sneakers to greet our teachers in the mornings after they had parked their Buicks, Datsuns, and Oldsmobiles in the faculty parking lot of Franklin Elementary School and, later, Edison Middle School.

Our teachers greeted us with enthusiasm, joy, and care. We helped them carry their belongings and our written assignments, which were gently packed and stored. And graded, too.

The word challenge meant more to me as the fifth-grade year moved from winter to spring time. What seemed like an ordinary day in January became an extraordinary day for learning through a current and difficult event unfolding before our eyes.

Something Else

In the article “Start Where Your Students Are” (2010), Robyn Jackson describes the differing expectations for schooling: “Good grades. A quiet classroom. These are often what teachers value. But, what if students come to class looking for something else?” (6).

In our fifth-grade class, we were excited about science and making observations and predictions with experiments. Our teachers gave us hope through the trying times we lived in long before and after school hours. Some of us knew firsthand about aches, turmoil, and unpredictability. However, in our classrooms, our teachers helped us forget—temporarily—and learning happened.

Our reading selections and language arts assignments engaged us and opened new worlds with layers of safety and hope that changed our lives. Our teachers became before our eyes. Leila Christenbury and Ken Lindblom note, “As you will see or have perhaps already glimpsed, becoming, the ongoing process of changing and shifting and redefining, is also part of the business of teaching” (8).

Human Footsteps

2017 marked my twentieth anniversary as a member of NCTE. I joined my senior year of undergraduate study while attending Kenyon College in the rural quiet of Ohio. I am glad I joined the ranks of educators who care about their students and are also dedicated writers, editors, and scholars across many spaces and communities that include the sciences.

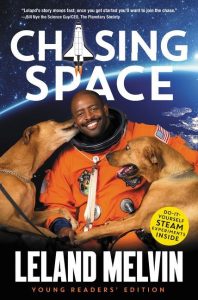

Other than a room or space of one’s own, what else does an educator or writer need to work? In the book Chasing Space, Young Readers’ Edition, Leland Melvin explains, “Humans have a deep desire to explore uncharted territory. I believe that desire will take us back to the moon and then on to the Red Planet. One day there will be human footsteps on Mars. Will they be yours?” (188).

Along with my peers, I was encouraged, praised, and admired in my learning of civics and the sciences, even as I struggled to learn elementary-level science, improve my reading skill, and earn good grades. Ms. Wiggins’s care and teaching opened our tiny worlds and envisioned something else for us—another space for growth, so we could take a giant leap with our imagination and learning, much like the words of Leland Melvin. Through my teacher’s interceding and care, I succeeded in fifth grade, and thereafter, with resilience.

In retrospect, the teaching life that had been modeled for me in fifth grade and by scientists exploring space propelled me to adopt the teaching life as my career, and I still live it today as a middle-aged adult.

References

Christenbury, L., & Lindblom, K. (2016) Making the journey: Being and becoming a teacher of English language arts (4th ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann

Joseph Rodríguez is the author of Enacting Adolescent Literacies across Communities: Latino/a Scribes and Their Rites (Lexington Books, 2016). He serves as coeditor of English Journal. Joseph has been a member of NCTE since 1997. Catch him virtually on Twitter @escribescribe.

Cover Photo: The author appears with his fifth-grade classmates in the second row and third from left.