This post was written by NCTE member Kyle Vaughn, author of Lightning Paths: 75 Poetry Writing Exercises (NCTE, 2018).

Poetry can be one of the most uncomfortable genres to teach. For many teachers, it is the genre they have had the least experience reading and writing, and analyzing it, particularly through pre-set methods, seems to check a box but never feel satisfying. For others, poetry carries an intensity that can send emotional shockwaves through the classroom, making it difficult to manage the resulting ideas and conversations. That one is difficult for me, too, though truly it is a sign that something is working, as it seems to bring the experience of the poem into being.

Having set out on a path as a poet before I even considered teaching, I confess that I brought an agenda with me to the classroom, but it’s one I have seen work time and time again. That agenda was to teach poetry through the experience of it: the beauty, the music, the physical force of it.

As a student, the analysis of poetry left me cold; frankly, I ignored it. Though this is somewhat a summary of my experience, I often relived the poetry I fell in love with in this fashion: internalizing it (emotionally rather than analytically), imitating it (trying my own writer’s hand at similar voices and images), and living it (seeing if I had or could have similar life experiences).

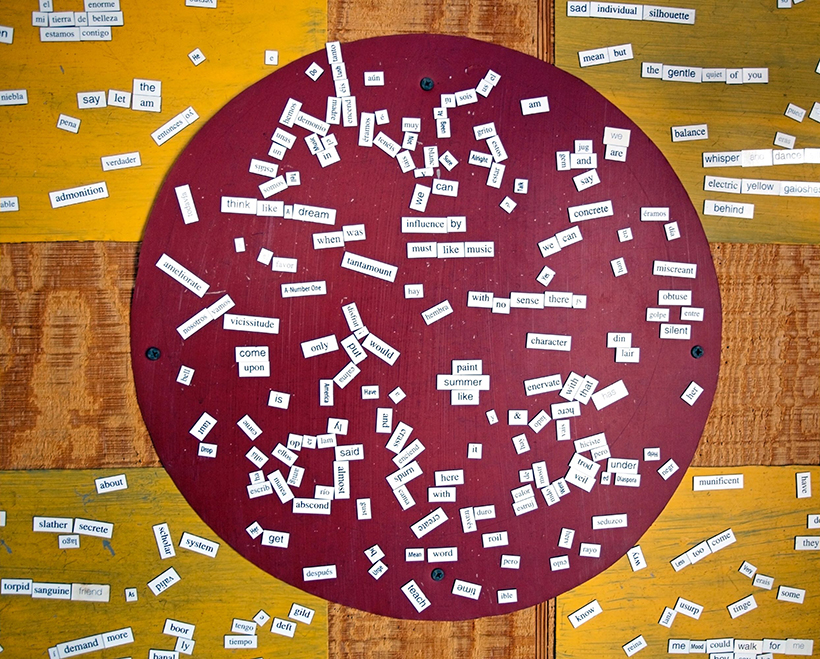

Teaching poetry experientially has brought many of my students closer to a genre that they often felt was inaccessible to them. I remind them that poetry is not a logic puzzle to be solved—more likely, it is an illogical one not to be solved. It is often a dream logic. It is a world to enter in and play. We draw our way through poems like “Kubla Khan.” We use manipulatives, such as cutting up each word in Seamus Heaney’s “Blackberry-Picking” and rearranging them to play with tone. We remove all the consonants from “Do not go gentle into that good night” and recite it solely as vowel sounds to hear how its power is absolutely unchanged.

And without a doubt, giving students an opportunity to write poetry is the best way to open them to its power and its potential in their personal lives. As I set out to collect many of the poetry writing exercises I have used with students over the years into my book Lightning Paths: 75 Poetry Writing Exercises, I asked myself what some of the common denominators in those lessons were.

Many of the commonalities in the exercises fell within that realm of experiencing poetry: how we experience imagery (imagery of the senses and beyond, into other types of imagery such as synesthetic); how we experience ideas that ultimately lead to inspiration (many of which come from beyond the world of words); and how we experience form (form seeming to need meaning as well as shape).

My hope for students as they explore poetry, whether reading or writing, is to maintain that connection between world and word.

My hope is that, just as I would not want them to give a cold, analytical reading to a poem, neither should they write their own poem by filling in the image of a tree because they have “learned” that about poetry, when their own experience might actually be more like that of Tim Seibles’s “First Kiss.” My hope is that they will get up and take poetry with them into their world.

One such exercise in Lightning Paths that encourages this world-and-word relationship is the “Poetry Triathlon.”

Just as an athlete in a triathlon would, the student poet must run, must physically interact with water, and must work something mechanical (as the triathlete would a bicycle) to complete a three-sectioned poem. And while never a triathlete, Wordsworth and his brisk walks in the Lake District certainly served as inspiration for how that experience of movement can have profound effect on our inner, creative voices. (As needed, creative accommodations can be found to ensure students with disabilities can participate as well.)

And even when poetry is solely an internal exploration, where the poet sits, thinks and writes at a desk, the poem’s experience is still manifested in words and images and can guide a reader down an electrified path (rather than one of rote logic). As an example of this, I would point to the ghazal, a Muslim form of poetry that I provide an exercise for in Lightning Paths. The form and the content of a ghazal are inseparable, unlike other forms of poetry. Its loosely related couplets, sometimes slightly elusive in nature, are bound together by the longing expressed in the poem’s content. In other words, a ghazal provides a way for the reader to experience longing rather than just read a record of it.

By providing young poets with guidance on how imagery recreates experiences, how rethinking sources of inspiration can reconnect them with their own experiences, and how form can sometimes provide a physical pathway for all of this, I believe that teachers can help them write poetry in more powerful ways.

These approaches serve as the underpinning for the 75 poetry writing exercises in Lightning Paths, exercises that seek to move students beyond technique and into the experience of the writing life. I hope that you will find there many electrifying, lightning paths for your students to travel.

Kyle Vaughn, author of Lightning Paths: 75 Poetry Writing Exercises, is a poet, photographer, and teacher. At the time of publication of this post, Vaughn was serving as English Department Chair at Pulaski Academy in Little Rock, Arkansas. For more information, visit www.kylevaughn.org